Organic chemistry 07: Carbonyls - organometallic nucleophiles, acidity and pKa

These are my notes from lecture 7 of Harvard’s Chemistry 20: Organic Chemistry course, delivered by Dr. Ryan Spoering on February 11, 2015.

Acid-base chemistry

Consider this:

HCl ↔ H+ + Cl-

The forward direction of this reaction is incredibly endothermic - it takes a lot of energy to break the bond, and will not occur under any reasonably achieveable conditions.

However, this reaction:

HCl + H2O ↔ H3O+ + Cl-

Is fairly favorable. In other words, when we say HCl is an acid, we just mean it’s ready to donate its proton to a suitable acceptor - it doesn’t just give the proton up for nothing.

The latter equation has Ka as follows:

Ka = Keq[H2O] = [H3O+][Cl-] / [HCl]

pKa = -log10(Ka) = -7 for HCl

This very favorable pKa of -7 indicates that the lone pairs on water have 107-fold higher affinity for the proton than Cl- does.

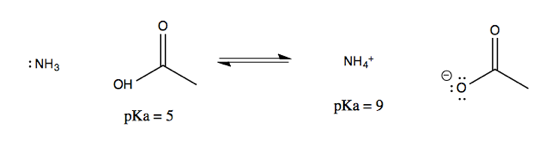

Now consider another reaction, of acetic acid and ammonia:

Note that on either side of the equation, it is the protonated species that can be described with a pKa. These pKas are well-established and can be looked up online, allowing you to figure out the equilibrium of the overall reaction. To do this, think of it as two half-reactions mediated by water:

By multiplying the Ka of the two half-reactions (or, think of it as summing the pKas) we can obtain an overall Ka for the reaction of 104. The equilibrium lies dramatically to the right, or in other words, the nitrogen lone pairs are much more affine for the proton than the oxygen lone pairs on carboxylic acid are.

What affects pKa?

The pKa of compounds depends on several factors.

| compound | pKa |

|---|---|

| H-F | 3 |

| H-Cl | -7 |

| H-I | -9 |

| H-OH | 16 |

| H-SH | 7 |

| H-NH2 | 38 |

| H-O+H2 | -2 |

| H-N+H3 | 9 |

| H-CH3 | 50 |

| H-ethene | 45 |

| H-ethyne | 25 |

*Note that for the species with pKa >20, they are such weak acids they would never give up a proton to water. The pKa values are based on extrapolations from measurements made in other solvents. **Note that ammonia appears twice: 38 is the pKa for NH3 to dissociate to NH2-, while 9 is the pKa for NH4+ to dissociate to NH3.

Here are factors that affect the values in the table above:

- Electronegativity of the atom bound to hydrogen. Hence why water has higher pKa than hydrogen halides.

- Size of electron shell. Among halogens, the size of the electron shell involved in bonding is so important that it overcomes the difference in electronegativity, hence why HCl has lower pKa than HF. Similarly, H-SH is a stronger acid than H-OH even though S is more electronegative than O.

- Bond strength and size matter. I wasn’t clear if this is a separate thing or just a re-statement of the “size” thing above.

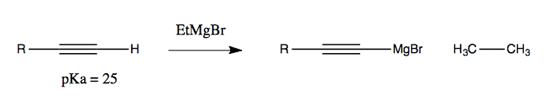

- Hybridization state. Hybridized orbitals with more s character are more willing to take on extra electrons. Thus, a triple bond (sp hybridized) more readily takes the electrons from a proton than a single bond (sp3 hybridized), which is why ethyne is more acidic than methane.

- Resonance. Cyclohexanol has a pKa of 16, while phenol has a pKa of 9, because the O- is able to share the extra electron density into the pi system of benzene. Another example is that ethanol has a pKa of 16, while acetic acid has a much lower pKa of 5 thanks to its double bond.

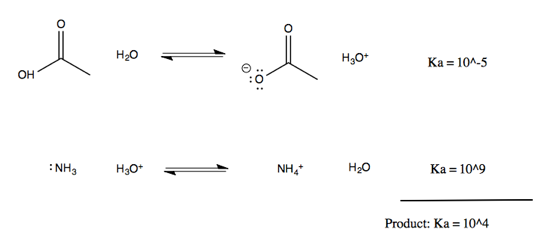

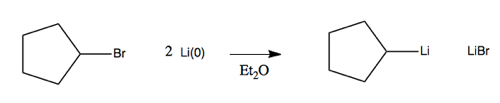

- Induction. The following three compounds differ in pKa not because of explicit resonance structures per se, but due to different ability to distribute electron density across the molecule via dipole moments. This effect is less strong than resonance.

This handout contains some additional useful pKas and concepts.

When you see a reaction, the quick way to figure out the Keq is as follows: ΔpKa = pKaproduct - pKareactant, and Keq = 10ΔpKa, where Keq values >1 indicate running forward is favored, and <1 indicate running in reverse is favored.

How to make the conjugate base of hydrocarbons

Alkyllithium reagents and alkylmagnesium reagents can make the conjugate base of hydrocarbons.

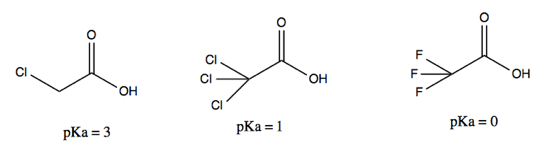

Alkyllithium reagents

Examples include methyllithium (CH3Li) or butyllithium (BuLi). These are quite reactive but are stable and can be purchased in a bottle. Here, the carbon is the electronegative partner. These are made via alkyl halides and lithium metal. For instance, in an aprotic solvent such as diethyl ether, you can react this alkyl bromide with lithium:

The notation Li(0) denotes that the lithium does have its electron, as opposed to being in the Li+ state. Li(0) is a 1e- reducing agent.

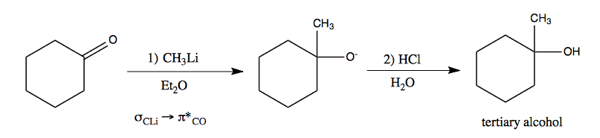

Now that we have alkylithium, here is how we can use it to perform addition to a carbonyl, resulting in a new carbon-carbon bond.

)

)

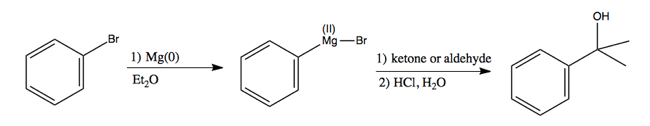

Grignard reagents

Another very famous example of this reaction is a Grignard reaction. These use Grignard reagents, which contain Mg instead of Li. They have the formula R-Mg-X. For instance:

In the first step, again Mg(0) denotes that Mg retains its electrons. This is simply magnesium metal, which can be chopped into pieces and added to the reaction.

What you can do with these

The choice of alkyllithium versus Grignard reagents is often just a practical one; you might try the reaction both ways and see which works better.

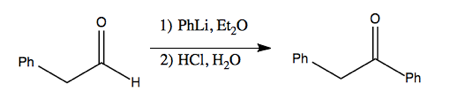

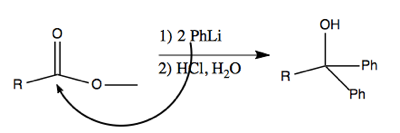

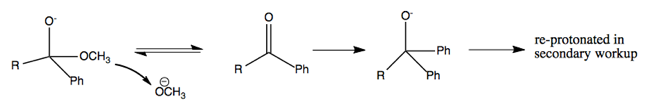

These reagents can even be used to perform addition to less reactive carbonyls, such as esters. This works via nucleophilic attack on the carbon, which creates a ketone which is even more reactive. The second equivalent of PhLi then attacks that, resulting in a deprotonated alcohol which is restored to a protonated state in the workup with HCl after it has run to completion.

For instance, this reaction proceeds via PhLi making a nucleophilic attack on the carbon in the ester.

The above reaction proceeds via multiple steps as diagrammed below. Here’s how I think I understand it. The first nucleophilic attack abolishes the double bond, and creates a new bond to phenyl, so that the central carbon has four bonds. The OCH3- then ionizes away (I think) and the O- re-forms its double bond with the central carbon. A second nucleophilic attack then abolishes the double bond again, such that now two phenyl groups are bound to the central carbon. This leaves you with O- as one of the groups, but by treating with HCl, you can reprotonate it. Thus you end up with a tertiary alcohol (a carbon with an -OH plus three other things bound to it).

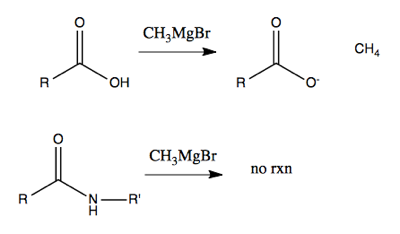

However, if you try to use alkyllithium or Grignard reagents on acids or amides, you’ll be disappointed. All they will do to acids is deprotonate them, creating (say) methane. (Although with very large amounts of heat and excess reagent you can force something to happen with acids). And they won’t do anything at all to amides.

Addition to alkynes is possible:

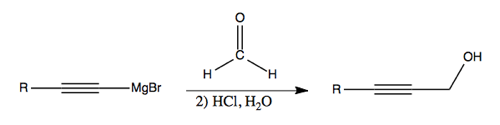

Formadelhyde (CH2O) is useful as a chain lengthening reagent. Here, it is shown converting an alkyne into a primary alcohol:

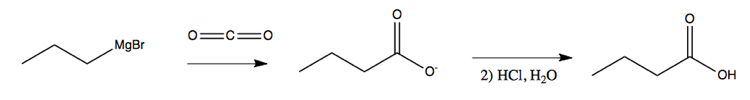

Grignard reagents can also be used to lengthen chains by simply bubbling CO2 gas through your solution:

In learning this material, one should not only remember what each reagent can do, and what solvents and conditions must be used, but also be able to recognize a product - say, a secondary alcohol - and figure out what sort of process could be used to create that product.