Biochemistry 07: glucose metabolism

These are notes from lecture 7 of Harvard Extension’s biochemistry class.

redox

Redox is incredibly confusing because it’s reciprocal: things that oxidize are themselves reduced, and things that reduce are themselves oxidized. One molecule’s loss of an electron is another molecule’s gain. It’s like when people say “everybody is selling” such-and-such stock: no, actually, the number of sells and the number of buys are by definition always equal.

A common mnemonic is OIL RIG – oxidation is losing (electrons), reduction is gaining (electrons). Here’s an attempt at an exhaustive description:

- A molecule is itself oxidized when it loses electrons, usually either by gaining oxygen or losing hydrogen. It by definition reduces something else.

- A molecule is itself reduced when it gains electrons, usually either by losing oxygen or gaining hydrogen. It by definition oxidizes something else.

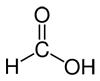

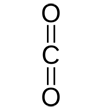

Here are several possible oxidation states of a one-carbon molecule.

| most reduced | ← | → | most oxidized | ||

| methane | methanol | formaldehyde | formic acid | carbon dioxide | |

| image |  |

|

|

|

|

| ΔG°oxidation (kJ/mol) | -820 | -703 | -523 | -285 | 0 |

Note that the more reduced it is, the more energy can be released by oxidizing it. Hence the thermodynamic favorability of burning methane for fuel to convert it to CO2. (technically the overall reaction is CH4 + 2 O2 → CO2 + 2 H2O and I think that the oxygen from O2 that becomes the water is technically what is being reduced).

In biological systems, oxidation is usually synonymous with dehydrogenation and is performed by dehydrogenases, such as lactate dehydrogenase. Ways for electrons to be transferred include as H atoms (1 proton, one electron), or as :H- hydride ions (1 proton, 2 electrons). Adding a hydride ion reduces NADH to NAD+. NAD+ can then be oxidized to NADH.

Fatty acid is more reduced than glucose. Fats are in a reduced state and so have a lot more free energy to release than carbohydrates. You can generate 130 molecules of ATP per molecule of 20-carbon fatty acid (energy of 9 kcal/g), but only 38 molecules of ATP per molecule of 7-carbon glucose (energy of 4 kcal/g, and the kcal/g figures are not proportional to the ATP figures due to different numbers of carbons).

group transfer

Addition of phosphate (PO43−, denoted Pi when unbound) group from ATP is used to convert glucose to glucose 6-phosphate which traps it in the cell.

The products of hydrolysis of ATP are more stable than the reactants, so the phosphoanhydride (P-O-P) bonds that hold the three phosphates together are high-energy bonds. Why?

- Phosphoanhydride bonds have less resonance stabilization than the hydrolysis products.

- ATP has 4 negative charges, which repulse each other a bit. Cleaving the bonds relieves this repulsion.

- The hydrolysis products (Pi and ADP) have greater solvation than ATP – i.e. they are more stabilized by dissolution in water than ATP is.

Coupling to ATP hydrolysis is often used to drive unfavorable reactions. ATP hydrolysis has ΔG°’ = -30 kJ/mol.

Phosphocreatine, phosphoenolpyruvate and others can also act as cellular energy sources. ATP is at the middle of the distribution of their energy levels, which makes it able to transfer Pi from the high-energy ones to the low-energy ones.

Transfer of P by a kinase is substrate level phosphorylation. Indirect ATP generation using energy from proton gradients (e.g. in the electron transport chain) is oxidative phosphorylation.

Besides phosphate groups, acyl and glycosyl groups are also often transferred. For instance, acetyl groups (a subset of acyl), usually from acetyl-coA. Hydrolysis of the thioester bond yields acetyl and coA.

overview of glucose metabolism

Here is a diagram of glucose metabolic pathways with links to those introduced in lecture.

glycolysis

Glycolysis takes place in two stages. Stage 1 (reactions 1-5) is an energy investment, using 2 ATP to phosphorylate one 6-carbon glucose to G-6P and cleave it in half yielding two 3-carbon molecules. Stage 2 (reactions 6-10) is the energy payoff, yielding two pyruvates and charging 4 ADPs to ATPs. Net ATP production = 4-2 = 2.

Here are the steps:

- ATP-dependent phosphorylation of glucose to G-6P so it cannot leave the cell.

- Isomerization to fructose 6-phosphate (F-6P).

- ATP-dependent phosphorylation of F-6P to fructose 1,6 bisphosphate (F1,6 BP).

- F1,6BP is cleaved into dihydroxyacetone phosphate and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate.

- Triose phosphate isomerase converts the dihydroxyacetone phosphate to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate so now you have two of the latter.

- 6-10 = conversion of these two glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate to two pyruvates (not discussed in detail)

Products of glycolysis.

- ATP. Generation of 4 ATP by substrate-level phosphorylation, minus investment of 2 ATP = net production of 2.

- NADH. Glucose is oxidized, reducing 2 NAD+ to 2 NADH. (Later reoxidation of NADH occurs throuh aerobic and anaerobic conditions).

- Pyruvate. 2 pyruvate per glucose will go on to aerobic metabolism in the citric acid cycle, or anaerobic metabolism into lactate to regenerate NAD+.

All systems need a way to re-oxidize NADH into NAD+. Here’s what they are.

- Aerobic: convert pyruvate to CO2 and oxidatively phosphorylate NADH.

- Anaerobic in animal muscle: homolactic fermentation converts pyruvate to lactate and NADH to NAD+.

- Anaerobic in yeast is alcoholic fermentation to yield CO2 and ethanol and convert NADH to NAD+.

In lactic acid fermentation, lactate is a dead end in the muscle so it is exported to the liver for gluconeogenesis in the Cori cycle. The enzyme involved in this process in the liver is not expressed in muscle.

gluconeogenesis

Gluconeogenesis is not just glycolysis backwards. It happens in the liver and to a lesser extent the kidney. Precursors for gluconeogenesis can come from amino acids, lactate or glycerol.

One interesting substrate cycle within the gluconeogenesis pathway is highly endergonic. Pyruvate carboxylase and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase each use 1 ATP to reverse the originally exergonic step (in glycolysis) of converting to pyruvate.

Most enzymes involved in gluconeogenesis are in the cytosol, but one – pyruvate carboxylase – is in the mitochondria. It converts pyruvate to oxaloacetate, which is then reduced to malate by oxidizing NADH to NAD+ in the mitochondria, then the malate is exported to the cytosol and oxidized right back to oxaloacetate while reducing NAD+ to NADH. This transfers “reducing equivalents” into the cytosol, which keeps the cytosol a reductive environment.

Blood glucose levels need to be maintained (buffered by the liver) because it is critical for brain function. The brain has negligible glycogen stores and cannot perform gluconeogenesis.

How is all this regulated?

1. Regulation of glucose entrance into the cell. Intracellular glucose levels are lower than in the blood, so a passive transporter GLUT4 can bring it in. Elevated blood glucose leads to elevated insulin leads to localization of GLUT4 at the cell surface. In the absence of insulin, GLUT4 is localized within the cell.

2. Regulation of the enzymes involved in the metabolic pathways.

The “substrate cycles” (G → G-6P, G-6P → F-6P, and phosphoenol-pyruvate → pyruvate) are the regulatory steps, they are irreversible and have large negative ΔG°. In the liver, the first committed step is not hexokinase beacuse just converting to G-6P, though it traps glucose in the cell, does not determine which pathway it will go down (glycolysis or glycogen synthesis). The first committed step is actually phosphofructokinase because then you are committed to proceeding all the way to pyruvate, i.e. to completing glycolysis.

Hexokinase is regulated in a tissue-specific manner. Hexokinase I and II (genes: HK1 & HK2) are present in muscle and have sufficiently high affinity for glucose (Km = .1mM) that they are often saturated, which is rate-limiting. The high affinity makes it possible to initiate glycolysis even when glucose is low. These hexokinases are allosterically inhibited by their own product, G-6P.

Hexokinase IV (aka glucokinase and gene symbol GCK) is expressed in the liver and has a much lower affinity for glucose (Km = 10mM) so it is rarely saturated. This is important because liver needs to always be able to act as a buffer. Hexokinase IV’s activity is mostly regulated by blood glucose levels themselves. When blood glucose levels are low, Hexokinase IV is not saturated and so glucose is metabolized at a lower rate. Hexokinase IV is also transcriptionally regulated. It is transactivated by persistent high blood glucose. Its antithesis, glucose-6-phosphatase (converts G-6P to G) is transactivated by persistent low blood glucose.

High ATP signals that ATP is being produced faster than it is being consumed, which means glycolysis should be downregulated and glycogen creation should be upregulated. High citrate also means that energy state is high and biosynthetic intermediates are abundant. Hormones (insulin and glucagon) also regulate glycolysis and gluconeogenesis.

Fructose 2,6 bisphosphate (F26BP) also plays an important role in regulating the enzyme PFK-2/FBPase-2 (a heterodimer; gene symbols PFK and FBP1). This acts as one bifunctional enzyme with two separate activities regulated by insulin and glucagon. Low blood sugar elevates glucagon which causes a cAMP-dependent protein kinase to phosphorylate PFK-2/FBPase-2. When phosphorylated the FBPase-2 domain is activated and inhibits glycolysis and stimulates gluconeogenesis. to respond to the low glucose conditions. When blood sugar gets high, insulin is released which causes a phosphoprotein phosphatase to dephosphorylate PFK-2/FBPase-2. When dephosphorylated the PKF-2 domain is activated and stimulates glycolysis and inhibits gluconeogenesis.

Does high fructose corn syrup really contribute to obesity? HFCS has been enzymatically processed to increase the proportion of sugar that is fructose. Fructose is processed into glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate / dihydroxyacetone phosphate, thus bypassing two regulatory steps at the top of the glycolysis pathway, the hexokinase and the phosphofructokinase. Thus fructose is not subject to regulation and will end up either terminating in glycolysis or glycerol 3-phosphate which will be converted to triacylglycerols which become “FAT”. Fructose also bypasses the insulin response and another response that is associated with a feeling of “fullness.”

glycogen synthesis and breakdown

Glycogen synthesis (from glucose) requires energy. Glycogen degradation is thermodynamically favorable. Liver, muscle, and to a lesser extent kidney use glycogen. The brain has negligible glycogen stores.

Glycogen is a polymer of α1-4 linked D-glucose with α1-6 linked branches every 8 to 14 residues. There is only one reducing end; other would-be reducing ends are lost to branching. Glucose is removed from non-reducing ends, not from the one reducing end. This means that glucose can be released from many different branch points at a time.

Glycogen synthesis takes place in 4 steps. The precursor is G-6P. You need glycogen synthase.

- Phosphoglucomutase mutates it to G-1P.

- 2. G-1P is activated with UTP (uridine triphosphate) to yield UDP-glucose, releasing PPi which becomes 2Pi, which is highly exergonic.

- 3. Glycogen synthase adds the UDP-glucose to the growing glucose chain, releasing UDP. It adds glucose to an existing branch.

- 4. When a branch gets long enough, a branching enzyme chops off the tip of a branch and reattaches it as a new branch. More branches is better because it means more sites from which to release glucose when it is needed.

Glycogen breakdown by glycogen phosphorylase:

- Glucose at the nonreducing end is “phosphorylized” to yield G-1P

- G-1P is converted to G-6P. Note that G-6P can enter glycolysis bypassing the hexokinase step, which saves you the investment of one ATP.

- In the liver only, glucose-6-phosphatase will remove the 6-phosphate to yield regular old glucose, which can then go back out into the blood for other organs to use.

Glycogen metabolism is regulated primarily at the glycogen synthase step (in synthesis) and at the glycogen phosphorylase step (in breakdown). These are allosterically and hormonally controlled. Phosphorylase is activated by AMP, inhibited by ATP and G6P. Synthase is activated by G6P. When there is high demand for ATP, that means ATP and G6P will be low while AMP will be high. Think about it.

Hormonal regulation of glycogen breakdown. During exercise and fasting, glycogen phosphorylase is activated by glucagon (in liver) or epinephrine (in muscle and liver). Either of these hormones activates a GPCR, leading to activation of adenylate cyclase, which produces cAMP which activates PKA which phosphorylatingly activates phosphorylase kinase which phosphorylatingly activates glycogen phosphorylase which removes a G-1P from glycogen. Meanwhile, the activated PKA also de-activates glycogen synthase.

Then later you eat a meal and need to switch back to glycogen synthesis. Insulin is released, which activates phosphopprotein phosphatase-1 (PP1) which then dephosphorylates two of the targets from the above cascade: glycogen phosphorylase, and phosphorylase kinase, inactivating them. PP1 also dephosphorylatingly activates glycogen synthase.

pentose phosphate pathway (PPP)

This is yet a third fate for G-6P. This pathway is active in tissues that synthesize either lipids (i.e. adipose) or nucleic acids (i.e. any rapidly dividing cell type, such as bone marrow and skin). PPP produces two products: NADPH which is used for reductive biosynthesis of fatty acids and cholesterol, and ribose 5 phosphate which is necessary for nucleic acid synthesis.