Genetics 09: 'Transduction and Recombineering: a CRISPR case study'

These are my notes from lecture 09 of Harvard’s Genetics 201 course, delivered by Tom Bernhardt on September 26, 2014.

Today’s lecture notes contain the example experiment started last time to test the “CRISPR immunity hypothesis”.

An example genetics experiment

Suppose we want to test the hypothesis that CRISPR/Cas systems confer resistance to phage. This vignette will be loosely based on the experiments of Danisco Inc., a dairy company in Madison, WI interested in combatting phage infection because it is a blight to yogurt production [Barrangou 2007].

We might start with (1) an E. coli strain that is sensitive to bacteriphage λ (this strain will be called λS) and which also has an active CRISPR/Cas system, and (2) a stock of λ. We’ll say the E. coli is at a concentration of 1e9 cfu/mL, where cfu is colony-forming units, and the phage is at at 1e9 pfu/mL, where pfu is phage-forming units. We could expose the bacterial to λ, selecting for cells resistant to death by λ infection, and then see if the resistant strains have gained a sgRNA complementary to phage DNA sequence. To do this, we’ll plate E. coli with LB and λ, and we’ll see only rare survivors - instead of a lawn we’ll have individual clonal colonies, and endpoint dilution will show that only about 1e-4 of the original bacterial population acquire resistance. For instance, when we plate 0.1 mL of a 1e-6 dilution of the E. coli on plain LB with no phage, we’ll find 100 colonies (X cfu/mL * 1e-1 mL * 1e-6 dilution = 100 cfu gives X = 1e9), indicating that there are 1e9 cfu/mL in the original culture. The 1e-6 dilution of bacteria on LB + phage will have no colonies, so we can’t learn anything from that. So suppose that with 0.1 mL of the 1e-1 dilution of E. coli on LB + phage we see 100 colonies. This would mean that 1e9 cfu/mL * 1e-1 mL * 1e-1 dilution * X = 1e2, where X is the frequency of resistant mutants. In this case, X = 1e-5, so we’ve demonstrated that resistance arises in 1e-5 of the bacteria.

Besides CRISPR, there are other potential resistance mechanisms - for instance, mutations in the λ receptor, which is called LamB. It is a “porin” protein in the outer membrane of E. coli which forms a pore that is required for the import of maltodextrins (glucose polymers). LamB- strains of E. coli cannot grow on “minimal DEX plates” where maltodextrins are the only energy source. This gives you a way to counterscreen to remove the receptor mutants which are not interesting if your goal is to test the CRISPR immunity hypothesis. Once you’ve counterscreened, you could sequence the CRISPR locus in the remaining colonies to see whether any have acquired genomic DNA sequences encoding sgRNAs against phage λ.

Suppose you find that certain resistant colonies do have genomic DNA encoding an sgRNA against λ. You would still want to confirm that this is really the cause of resistance. To show that the sgRNA is necessary, you could delete it and show that the colonies become λ-sensitive. To show that the sgRNA is sufficient, you could clone it into a λ-sensitive strain of E. coli and show that they become λ-resistant. This latter process is called transduction and is easier than the former experiment of deleting the sgRNA-encoding sequence from the original strain.

Transduction

In order to perform transduction, ideally you will want a drug resistance cassette closely linked to the CRISPR locus, so you can use it for selection. Suppose that at the beginning of your experiment you added a chloramphenicol resistance cassette just downstream of the CRISPR locus. Now infect the “donor strain” of interest with a high titer of phage P1, and within seconds you will see your culture go from turbid (many living cells) to clear (dead, lysed cells). The lysate now contains a huge number of P1 phage particles, each of which contains about 100kb of DNA. Usually this is just the original P1 DNA, but <0.1% of the phage particles will by chance contain E. coli host DNA instead of P1 phage DNA, and of those 0.1%, some subset will happen to contain the CRISPR locus.

Now add your phage particles to a new “recipient strain” of originally λ-sensitive E. coli. The bacteria that become infected with phage particles containing live phage DNA (which is 99.9% of viral particles) will be lysed, and so the vast majority of cells in your recipient strain will die. The <0.1% of cells infected with phage containing E. coli DNA will survive. Some subset of those will contain the CRISPR locus. Meanwhile, though, the live phage particles released by the other bacteria that got lysed will be attacking the remaining cells. Luckily, Ca2+ is necessary for λ infection, so by adding citrate as a calcium chelator about 20 minutes after the original infection event, you can prevent further infection. Now finally you can re-plate on media with LB plus chloramphenicol to select only the subset of the survivors that contain the CRISPR locus. These survivors are called transductants. Now test these for λ resistance, and sequence the λ-resistant transductants to see if they indeed acquired the sgRNA against λ.

Your transduction results might look like this:

| Count of λS colonies | Count of λR colonies | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 100 | 0 | CRISPR locus not sufficient to cause λ resistance |

| 20 | 80 | CRISPR locus is sufficient for λ resistance; the other 20 clones probably got the chloramphenicol cassette but not the CRISPR locus, due to insufficient linkage. You can sequence them to confirm this hypothesis. |

Allelic replacement

While the above-outlined experiment might give you results consistent with the CRISPR immunity hypothesis, the fact that you’ve added ~100kb of DNA to your recipient strain means it is impossible to show that the ~20bp of DNA encoding the sgRNA against λ are the cause of λ resistance. To do that, you’ll want to add a much smaller piece of DNA to your bacteria using allelic replacement, also known as “loop-in, loop-out”.

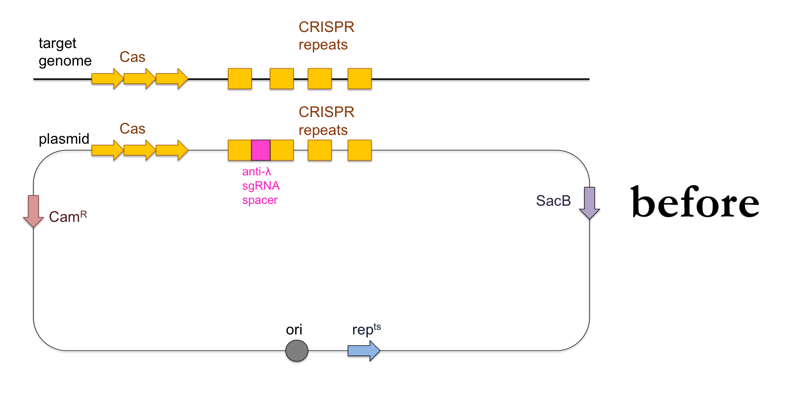

- Use PCR to amplify a product containing the CRISPR locus with the anti-λ sgRNA, with about 500 bp of homology on either side to the CRISPR locus of the recipient strain.

- Clone your PCR product into a plasmid containing a chloramphenicol resistance cassette (CamR), a sucrose sensitivity gene (SacB) and a gene that makes the plasmid temperature-sensitive so it can only replicate at 30°C and not at 42°C (repts). Note that the E. coli containing this plasmid can still replicate at 42°C but the plasmid itself will not replicate. The plasmid’s origin of replication (ori) will be located just upstream of the repts cassette.

- Transform wild-type (λ-sensitive) bacteria with the plasmid on LB + chloramphenicol at 30°C.

- Perform a second round of selection by re-streaking your transformants on more LB + chloramphenicol media.

- Grow a flask worth of culture in LB + chloramphenicol at 30°C.

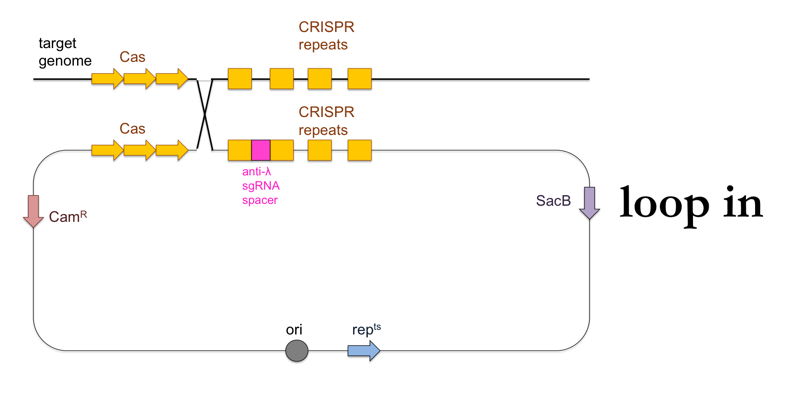

- Plate the culture on LB + chloramphenicol at 42°C. The temperature will halt replication of the standalone plasmid, so that the survivors at this stage will be those cells in which the plasmid was integrated into the genome (“loop in”).

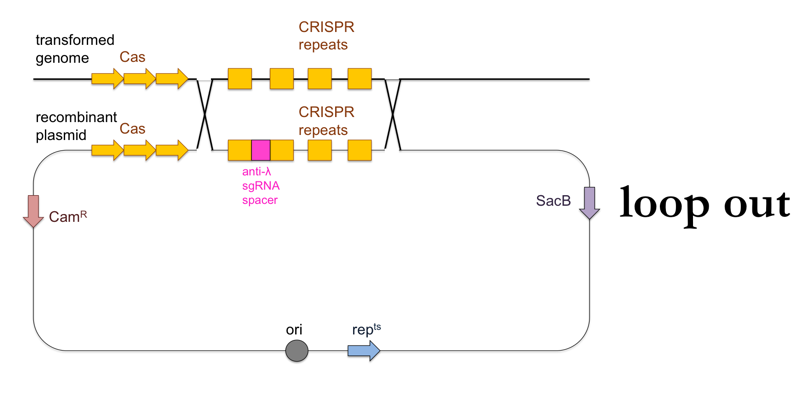

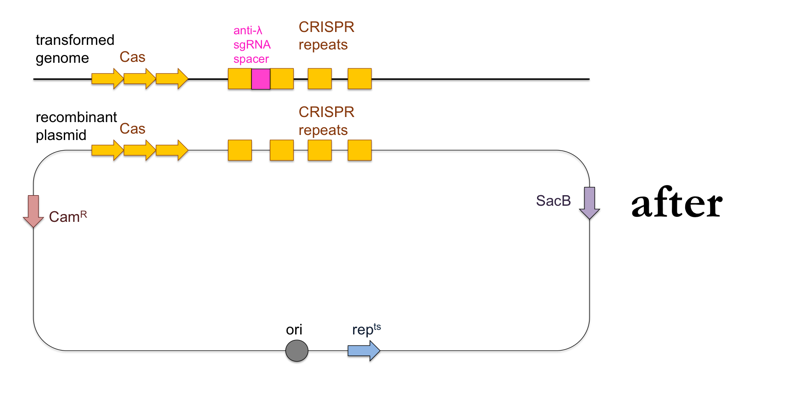

- Now plate transformants on LB + sucrose. This further selects for cells in which a second, non-allelic homologous recombination event occurs which removes the rest of the plasmid besides the desired CRISPR locus (“loop out”). These cells will have become sucrose-resistant, and will also have lost the chloramphenicol resistance.

- Test your remaining transformants for λ resistance, and if you find resistant clones, sequence them to confirm presence of the DNA encoding the anti-λ sgRNA.

This is what this process looks like:

Next time we’ll discuss how to create knockouts.