Genetics 12: 'How to do a C. elegans screen'

These are my notes from lecture 12 of Harvard’s Genetics 201 course, delivered by Max G. Heiman on October 15, 2014.

Scene setting

The year is 1963. You are Sydney Brenner and you’ve made major contributions to deciphering the genetic code and showing the existence of an unstable RNA intermediate between DNA and protein. You write a letter to Max Perutz declaring your concern that the big problems of genetics will be solved soon and you need a new challenge. You propose to study development and the nervous system - these are the two areas you’d like to devote the rest of your career to. This means you need to “microbiologize” these questions: deal with them at the molecular level using techniques established in bacteria and bacteriophages. You want to assemble a “parts list” for these processes. THis means to identify all the genes involved in development or nervous system processes by “saturating mutagenesis” - screening so many mutations that by the end all you are seeing is additional mutations in already-identified genes. This means you need large numbers of organisms - like you’re used to having for bacteria - and a way to easily maintain, archive and distribute mutants. The ideal organism could be frozen for archiving and could be mailed around the world in regular padded envelopes. You also want “stereotypy” - well-defined cell types that are reproducible from organism to organism. Therefore you want a simple organism with genetically hard-wired anatomy. Ideally this organism should also be transparent so that you can see all of this anatomy with microscopy.

Who you gonna call? Roundworms.

The life of C. elegans

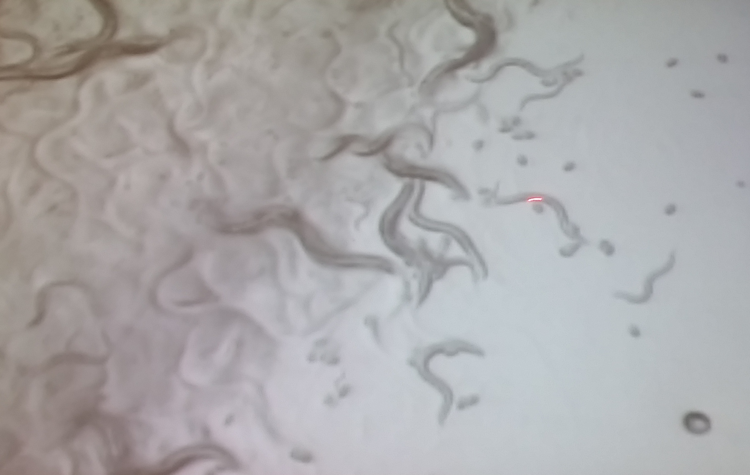

C. elegans meet all of the requirements listed above. Plus they can be grown on plates similar to yeast or bacteria. They require little care, as they can be frozen, or left without food for months and not starve to death. They are self-fertilizing hermaphrodites which means you can grow them clonally†, or you can do crosses.

†We say “clonal” here, even though if your parent is heterozygous for any markers, then the offspring will not be genetically identical to each other or the parent. If you have inbred strains, then your offspring will essentially be clonal. In this regard, C. elegans are similar to Mendel’s peas, which are also self-fertilizing hermaphrodites.

C. elegans all have 5 autosomes. Hermaphrodites (commonly referred to with female pronouns - “she”, “her” etc.) have two X chromosomes. Males (“he”, “him” etc.) have one X chromosome, and the missing spot where the other X would be is written O by convention. At the fourth larval stage (L4), both hermaphrodites and males generate sperm. At adulthood, the males continue making sperm, while the hermaphrodites switch to making oocytes. <0.5% of individuals will spontaneously be male, but a higher proportion of males can be induced via heat shock. Alternately if you cross a male with a hermaphrodite, you will get 50% males and 50% hermaphrodites.

Each adult lays several hundred eggs. From eggs you go through larval stages L1, L2, L3, L4 over the course of 4 days at 20°C. These stages mostly just involve increases in size, though gonad development does occur later in the process. If starved in the L2 stage, larvae will avoid L3 and instead form dauers, larvae in dormant state which are very hardy extraordinarily hardy and have been shown to survive space flight. If exposed to food again, the dauers will advance to L4. From L4 the worms advance to adults. Worms eat bacteria and are grown on plates covered in bacterial lawns.

The researcher moves worms around between plates using a “worm pick” which is a Pasteur pipet with platinum tip. Platinum heats and cools very quickly, so it can be sterilized in an old school ethanol lamp, then dipped in bacteria and then used to pick up a worm from one plate and place it down on another plate.

Above: Max Heiman moving C. elegans around with a worm pick.

The male has a brush-like structure at its tail that it uses to feel along the hermaphrodite to find the vulva (which is in the middle of the body) and insert its sperm.

C. elegans screens

Sydney Brenner introduced the world to C. elegans as a model organism in a single enormous paper [Brenner 1974]. He developed two types of screens:

- clonal screens are analogous to replica plating with bacteria. You screen individual mutants in arrayed form, and it is laborious but you have the ability to identify mutants that are sick or dead.

- non-clonal screens are analogous to a selection screen with bacteria. You pool mutants and it is quick but you have the limitation of only being able to identify mutants that proliferate.

How to do a non-clonal screen

To do a non-clonal screen, you mutagenize a L4 larva (the P0 generation) with EMS. This will result in mutagenizing the soma (somatic cells) but that’s not the point - the point is you have mutagenized each and every germ cell, so that each ova and sperm has different mutations. You grow the L4 to adulthood and then self-fertilize it. The offspring are F1s. Each F1 will be heterozygous for many different mutations - the probability of happening to get the same mutation in a sperm and an egg is very small, so homozygosity is rare. The average F1 will have about 20 “phenotype-causing” mutations. You self-fertilize the F1s, and the resulting F2s will each be homozygous for, on average, 5 mutations (1/4 of 20, according to Mendelian segregation).

C. elegans have about 20,000 genes, so you can figure that if you screen 4000 F2s each homozygous for 5 mutations, then you’ll get to an average of 1 mutation per gene. Once you get good at it, you can phenotype one worm in about 5 seconds, so doing such a large screen takes a day or so of labor. Such ease of screening large numbers makes it possible to approach saturation.

How to do a clonal screen

Clonal screens begin the same as non-clonal screens, with mutagenizing a single P0 at stage L4. Then in the F1 generation you separate each single F1 into its own plate before self-fertilizing (“selfing”) them. Then you breed the F2s in that same plate. As a result, if the homozygotes for a given mutation die, you’ll see 1/4 of the offspring are dead, so you’ll know it was lethal, and you’ll also have the ability to recover a copy of that lethal mutation by picking heterozygotes. Clonal screens take longer than non-clonal (because in addition to 5 seconds to phenotype each worm you also need to re-plate it), but an additional perk (besides identifying lethal mutants) is that you know exactly how many F1s you have screened

To look for temperature-sensitive mutants, you can pick F2s and make clonal populations at a permissive temperature, then copy them over to a high temperature plate to see which die. It’s like replica plating is for bacteria.

Brenner’s mutants

Brenner looked for worms with movement defects as a proxy for nervous system defects. He looked at an “uncoordinated” phenotype dubbed Unc, found hundreds of mutants in a non-clonal screen and by complementation testing was able to identify 69 distinct genes that caused Unc. In a subsequent clonal screen he was able to identify additional genes he had missed in the non-clonal screen.

The Unc mutants come in a number of subtypes. One phenotype called “roller” is when the worms rotate on their long axis when trying to move. There are dominant alleles that cause this phenotype, so it is sometimes used as a linked marker in transgenesis (analogous to auxotrophic markers in yeast).

C. elegans nomenclature

| example | rule | |

|---|---|---|

| gene | unc-22 | lowercase, three letters hyphen a serial integer |

| allele | e66 | letter for lab, serial integers within lab. sometimes additional information is added at the end, e.g. e66ts for a temperature-sensitive mutant. |

| strain | cB66 | two-letter code for lab (not same as the code for alleles), then serial integers |

| protein | UNC-22 | all caps, three letters hyphen a serial integer |

| phenotype | Unc | initcaps, three letters |

| genotype | unc-22(e66)IV; dpy-7(e88)X | gene(allele)CHROM;, repeat as necessary. chromosome number is in roman numerals. unless specified, all alleles are assumed homozygous. wild-type is denoted +, e.g. unc-22+, and deletions are denoted ø, e.g. unc-22ø |

These standards were established by Brenner and are still rigorously enforced today at wormbase.org, the go-to resource for all things worm genetics.

What to do with mutants

Once you’ve identified worm mutants, typical next steps are:

- Quantify the phenotype

- Determine dominance/recessiveness, X-linkedness.

- Complementation

- Linkage

The procedures for all of these are closely analogous to those for yeast, with the exception of dominance and X-linkage which is slightly different.

Dominance and X-linkage

To determine a mutation’s inheritance pattern, cross a wild-type male with a homozygous mutant hermaphrodite. Your F1s will be 50% male and 50% female. Supposing your mutant is Unc, here’s how to interpret results:

| F1 males | F1 hermaphrodites | interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| non-Unc | non-Unc | X-linked recessive |

| Unc | Unc | dominant |

| Unc | non-Unc | X-linked recessive |

| none | Unc | mating failed |

For dominant mutations, this won’t tell you if the mutation is X-linked or not.

In the final row, note the interpretation is NOT that the mutation is X-linked recessive and lethal - if it were, you would never have obtained homozygous mutant hermaphrodites in the first place. Instead, the likely explanation is that the mating failed, and the hermaphrodite offspring are actually self offspring rather than cross offspring.

The need to distinguish self progeny from cross progeny has been called a curse of hermaphrodite genetics. One solution is to incorporate a dominant marker (e.g. GFP expression) in the wild-type males, and then only look at the F1s that inherited the dominant marker. Another is to incorporate a known recessive mutant in the hermaphrodites (e.g. Dpy) and only look at non-Dpy F1s.

Complementation

Suppose you have two Unc mutants m1 and m2. Cross an m1/m1 male with a m2/m2 hermaphrodite. Assuming you have found a way (see above) to only look at cross progeny, all of the cross F1s will be heterozygous for both mutations. If they are Unc, you have non-complementation (i.e. m1 and m2 are in the same complementation group and probably the same gene). If you they are non-Unc, you have complementation (i.e. different complementation groups and presumably different genes). Just as with yeast, there are a variety of ways that complementation tests can trick you.

Sexual reproduction requires more effort on the part of the male than the hermaphrodite, so while viable mutant hermaphrodites can almost always “be mated with” by a male, many mutant males are unable to mate. This requires special designs for crosses.