Genetics 22: 'Genome variation in humans'

These are my notes from lecture 22 of Harvard’s Genetics 201 course, delivered by Steve McCarroll on November 12, 2014.

Introduction: why humans?

Why study genetics in humans as opposed to model organisms?

Pros:

- Uncover the basis of human diseases.

- We can study things unique to human biology. For example, psychiatric disorders have so far proven nearly impossible to model in other organisms.

- Rich phenotyping. People can self-report their own phenotypes. We can recognize subtle phenotypes in our fellow human that might be hard to see in mice. The medical system allows for ascertainment of rare phenotypes.

- Abundant data. Health care systems can aggregate huge amounts of medical data (particularly in Scandinavia, less so in the U.S.). There is an impressive amount of human genomic data available online, and many studies have been done using nothing but publicly available data, combined with a new computational approach.

- Tools and databases. Most bioinformatic tools are tested to work first and foremost on human data.

Cons:

- Purely observational. No mutagenesis, no crosses. Limited access to different tissues.

- Generation time.

- Large genome.

- Genomic privacy.

I would add population substructure as another con, at least for association studies, but Dr. McCarroll’s group has managed to make this an asset for other types of studies [Genovese 2013].

Facts about the human genome

- 3 Gb

- ~1.5% protein coding sequence†

- ~22,000 protein-coding genes

- 22 autosomes, X, Y and MT

- The “average” protein-coding gene spans 50kb of the genome and has a 1.5kb coding sequence and 10 exons.

†I’m not sure where this exact figure comes from. The latest Gencode CDS intervals when I was working with them in July 2014 added up to 35,345,952 bp, while the hg19 reference genome is 3,137,161,264 bp. That’s 1.1%.

How do human genomes vary?

Single nucleotide variants (SNVs)

The term single nucleotide variant (SNV) is preferred over SNP in many cases because it carries no connotation regarding allele frequency. Many people reserve the term “polymorphism” for things with an allele frequency over, say, 1%, while SNV could refer to somebody’s private variant.

Most alleles are bi-allelic, but that this depends on how many people you sequence.‡

‡In the >60,000 individuals in ExAC, for instance, we have 10.4 million alt alleles at 9.6 million sites, with 92% of variable sites being bi-allelic.

select count(*) from exac_annos;

Result: 10450724

select count(*) from (select CHROM, POS from exac_annos group by 1,2) subquery;

Result: 9579712

select case when N_ALT < 6 then N_ALT else '6 or more' end N_ALT, count(*) N_SITES

from (

select CHROM, POS, count(*) N_ALT

from exac_annos

group by 1,2) subquery

group by 1

order by 1

;

| number of alt alleles | number of sites |

|---|---|

| 1 | 8800902 |

| 2 | 714028 |

| 3 | 50038 |

| 4 | 6843 |

| 5 | 3126 |

| 6 or more | 4775 |

Insertions and deletions (INDELs)

Like SNVs, the bi- vs. multi-allelicness of indels depends on the number of individuals sequenced.

Simple tandem repeats (STRs)

STRs have a much higher mutational rate than SNVs and INDELs and are therefore much more likely to be multi-allelic across a smaller number of individuals

STR length variation is visible on gels, which is why historically they were more often used as markers (called “microsatellites”). In modern times, however, SNVs have become far easier to genotype. Currently a genotyping chip for 500,000 SNPs goes for $50.

Allele frequency

An allele’s allele frequency is the allele count over number of alleles genotyped.

What does “wild-type” mean?

Human genomes have an enormous reservoir of functional polymorphism.

When compared to the reference genome, the average person has:

- 15,000 exonic missense variants**

- 100 loss-of-function variants, 20 of which are homozygous

- 1,000 variants affecting gene expression

- 50 de novo mutations

**The following SQL query on the ExAC data double-counts homozygotes but most variants in any one individual’s exome are heterozygous so this won’t be off by too much:

select sum(AC+0.0)/(max(AN+0.0)/2) from exac_annos where Consequence like '%missense%';

Result: 14694.49825

History of human genetic variation

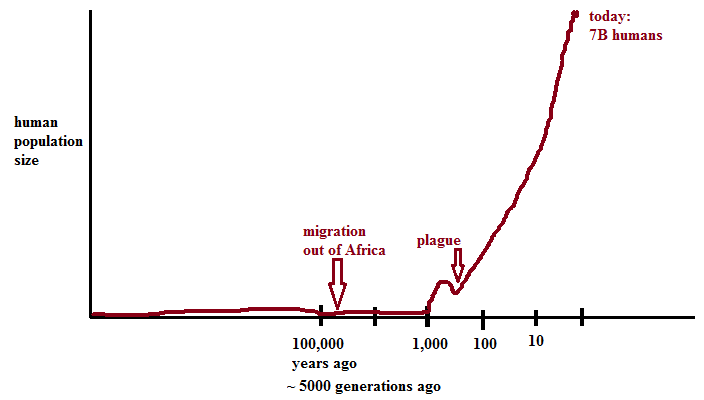

Drawing of Steve McCaroll’s plot of human population size courtesy of Sonia Vallabh

Ancient variation (pre-dating the out-of-Africa bottleneck) is mostly common today. These variants are found in millions or billions of people, on every continent. Such variation is limited - there are about 20M common SNPs. Such variation can be readily catalogued. These SNPs are readily genotyped on arrays and were phased in HapMap.

Recent variation is mostly rare - for instance, if the 7 billion people alive today have on average 50 de novos per genome there are 350 billion private variants. Such variants are accessible only by sequencing.

The vast majority of human genetic variants are rare. For example, 99% of ExAC alleles have allele frequency <1%:

Half of ExAC alleles are singletons, and ~99% have <1% frequency. From @dgmacarthur's talk at #ASHG14 pic.twitter.com/BbKjHQyPZx

— Eric Vallabh Minikel (@cureffi) October 20, 2014