Organic chemistry 01: What is organic chemistry, drawing structures

These are my notes from lecture 1 of Harvard’s Chemistry 20: Organic Chemistry course, delivered by Dr. Ryan Spoering on January 26, 2015.

Introduction

Organic chemistry is the chemisty of carbon compounds.

The first organic chemistry synthesis was conducted accidentally by Wöhler in 1828, about 40 years before the periodic table. Wohler was studying the organic compound silver cyanate (AgOCN) and an isomeric ion fulminate (CNO-). At that time, people were just beginning to realize that molecules were made of atoms in stoichiometric ratios, and Wohler was trying to understand the difference between silver fulminate, which is highly explosive (mercury fulminate, a similar compound, made a cameo in Breaking Bad) and silver cyanate, which is not explosive. He mixed silver cyanate with ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) and heated it, expecting to obtain NH4OCN, but instead obtained AgCl + CH4N2O - the latter being actually CO(NH2)2 or urea. This showed that urea, which was then known only as an excreted metabolite of animals, could be created synthetically.

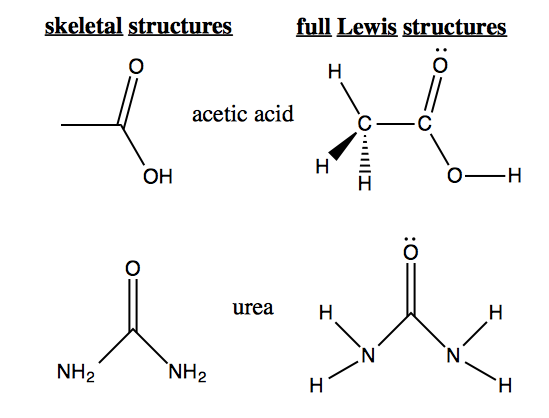

Lewis structures are the drawings with dots for electrons. To validate a Lewis structure, there are two rules:

- Octet rule - each atom should be surrounded by eight electrons

- Balance and minimize formal charge

And note that some compounds have resonance structures. We now know that cyanate and fulminate are as follows:

Each has (count them) 16 e-: 6+4+5+1

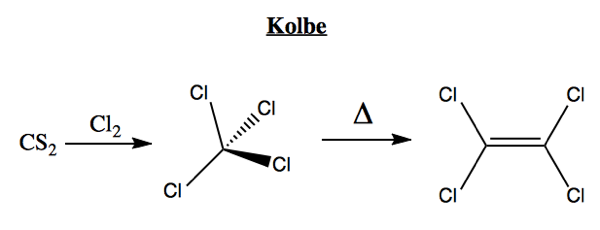

The next organic synthesis took place in 1845, by Hermann Kolbe. He reacted carbon disulfide with chloride to obtain tetrachloroethylene (best known for its role in dry cleaning), as follows:

Skeletal Lewis structures draw carbons simply as vertices, and all electrons and hydrogens are implicit. As examples, the following molecules are drawn in both forms:

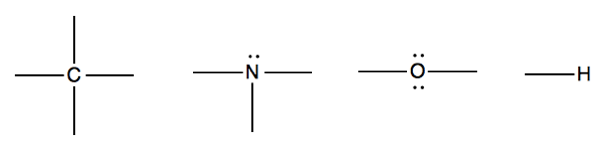

When drawing Lewis structures, remember the constraints on each type of atom:

In 1870, Thomas Huxley called the above experiments an example of a beautiful hypothesis slain by an ugly fact. The “beautiful hypothesis” was vitalism, then a mainstream theory that there existed a vital force separating the living from the nonliving. These experiments suggested that life was in fact built of the same materials as nonlife. Some scientists such as Louis Pasteur continued to belive in a vital force into the early 1900s, but this theory eventually fell from scientific discourse. Yet vitalism still appears in popular discourse today, for instance in homeopathy and food marketing.

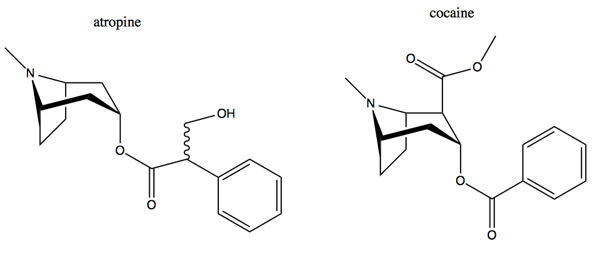

Atropine is a highly toxic organic compound found in nightshades such as belladonna, tomato and potato leaves. Many other tropine alkaloids are less toxic but tend to be avoided because people associate them with atropine. Atropine and cocaine share a backbone.

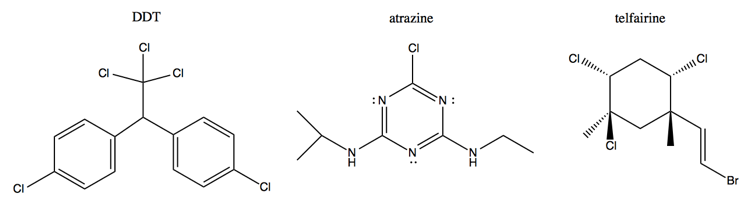

Above are three pesticides: DDT, atrazine and telfairine. All three are quite toxic. Yet because DDT and atrazine are synthetic, they are not permitted in organic food, whereas teifairine, which comes from a marine plant, is permitted.

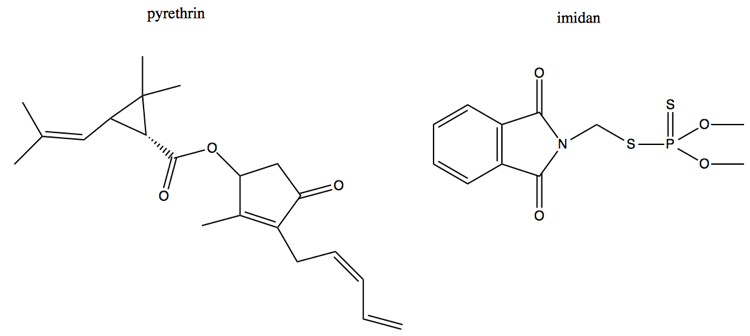

Here are another two pesticides, pyrethrin and imidan. Pyrethrin is natural - it comes from chrysanthemum - and therefore very widely used and accepted, but is highly toxic and kills marine life, whereas imidan is probably less enviromentally harmful but is less often used because it is synthetic. This is another example of vitalism.

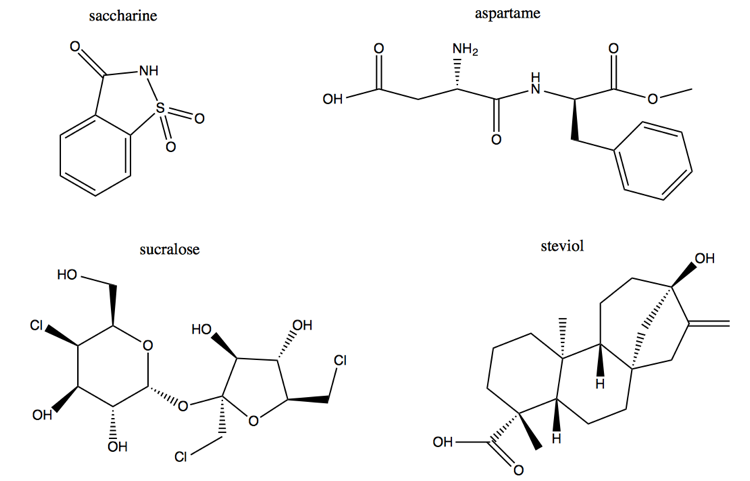

Above are four molecules unrelated in structure, which all serve the same function: they are artificial sweeteners. Saccharine is now rarely used. Aspartame is a dipeptide. Alone among the four, sucralose bears some resemblance to glucose. It is in fact synthesized starting from glucose, via 6 reaction steps with toxic chlorinating agents. Taking advantage of the fact that glucose is one input to the synthesis, the original, highly effective advertising campaigns for sucralose (Splenda®) stated that it is “Made from sugar, so it tastes like sugar”. The aspartame manufacturers sued them for deceptive advertising, and they changed their tagline to “It starts with sugar. It tastes like sugar. But it’s not sugar.” The fourth molecule is a steroid or terpene called steviol. Its only competitive edge over the other molecules is that it comes from a plant, stevia.

In considering 3D structures, we must obey valence shell electron pair repulsion (VSEPR). Carbon is tetrahedral, and the angle between any two of the hydrogens in methane is ~109.5°. Nitrogen is also tetrahedral, but its lone pair takes up more space, further comrpessing the hydrogens, such that the angle between any two H in NH3 is 107°. In water, oxygen has two lone pairs, so the angle between the hydrogens is 104°.