Organic chemistry 06: Carbonyls - nucleophilic additions, oxidation and reduction

These are my notes from lecture 6 of Harvard’s Chemistry 20: Organic Chemistry course, delivered by Dr. Ryan Spoering on February 6, 2015.

Carbonyl addition reactions

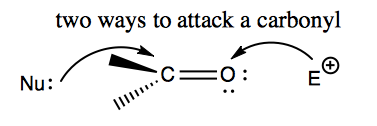

Carbonyl is electrophilic at the carbon, willing to accept electrons from an incoming nucleophile. It also has sufficient electron density on the O that it could act as a nucleophile, if it met a sufficiently electrophilic group.

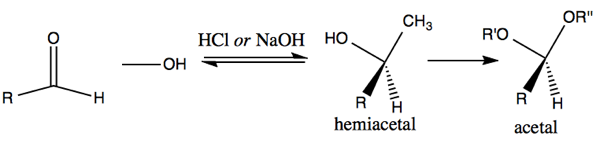

In hemiacetal formation, a carbonyl reacts with an alcohol - here, methanol as an example - and, catalyzed by either acid or base, forms a hemiacetal which can go on to form a full acetal.

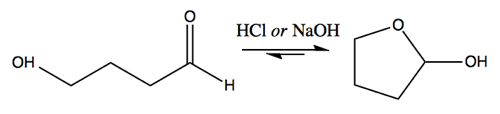

For most aldehydes and ketons, the carbonyl (left) is favored; the reaction will not usually run forward. However, an exception is cyclic hemiacetals:

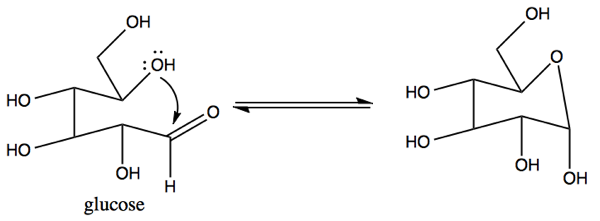

Here, the product at right is more stable. The change in enthalpy of this reaction is about the same as for the non-favored hemiacetal formation, but here the entropy is far more favorable, for reasons I did not fully understand. According to this lesson the reason is that cyclic acetal formation converts two reactants to two products rather than three reactants to two products, thus avoiding a loss in translational entropy. Anyway, an example of this stucture in nature is sugars:

One is encouraged to look hard at the above diagram and see how it is actually the same as the hemiacetal formation diagrammed further up top.

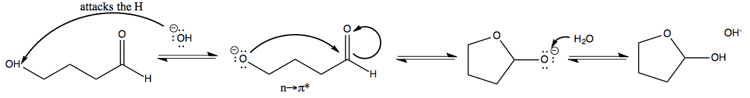

Now, what is the mechanism of hemiacetal formation? First let us consider the case of base catalysis:

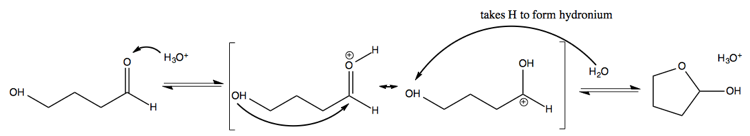

Acid-catalyzed hemiacetal formation has the same end, but different steps:

)

)

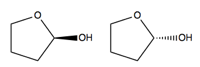

Note that although we’ve drawn the molecule as planar as a simplification, what we get is in fact a 50/50 mix of two chiral molecules:

Now let’s consider some irreversible reactions. Hydride reactions involve for instance sodium hydride (NaH), which is basic in the Lewis or Bronsted-Lowry sense. Because Na is so electropositive, it acts almost as if it were hydride, H-. If you react an alcohol with sodium hydride you get hydrogen gas bubbling out, and a sodium oxide. This is a way of making a conjugate base.

R-OH + NaH → R-ONa + H2

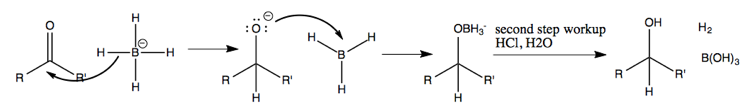

We’ll also consider sodium borohydride (NaBH4), which is also a nucleophilic H--like reagent. We can use NaBH4 to reduce reactive C=O bonds. It releases a BH4- ion, which is tetrahedral but will be drawn planar for simplicity. It has a reactive high energy σ bond, and is nucleophilic. If quenched with water it would take a proton and make hydrogen gas. If reacted with carbonyl, it will attack the carbon.

This is a way of making secondary alcohols (or primary alcohols). However it will not do anything if the carbon is bound to a heteroatoms, including N or O.

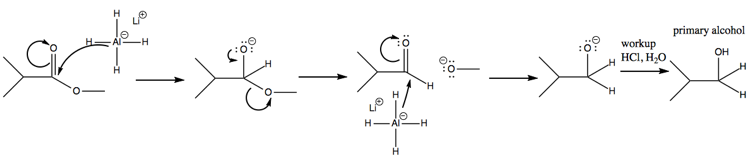

If we want to do something to molecules with a heteroatom in that position, then we need a nastier reagent called lithium aluminum hydride. It is extremely reactive and pyrophoric, meaning it will explode when it touches water (or anything with a proton that can be ripped off) including if just exposed to the atmosphere, so it has to be handled with the utmost care. The Al- is sufficiently nucleophilic to attack the carbon even if bound to N or O. This yields a primary alcohol from the original ester, via two hydride additions.

This sort of reagent, such as aluminum hydride, will just keep reducing things until they get to the alcohol oxidation state.

You can also use aluminum hydride with diethyl ether (Et2O), to make primary alcohols, amides, or also nitriles (not shown).

Oxidation of alcohol to carbonyl

All of the above reactions are irreversible. Therefore, going the opposite direction - from an alcohol to a carbonyl - requires a whole different pathway. There are loads of different ways of achieving this. We’ll introduce Collins reagent, which is CrO3·pyridine (“a chromium trioxide pyridine complex”). Together with CH2Cl2 it can revert the secondary alcohol into a carbonyl, or a primary alcohol into an aldehyde.

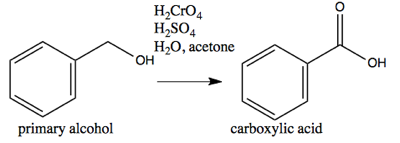

Another option is Jones reagent, which is also chromium in a very high oxidation state, in this case chromic acid (H2CrO4). Together with H2SO4, H2O and acetone, it can convert a primary alcohol into a carboxylic acid.