Organic chemistry 08: Carbonyl conjugation, conformational analysis, cyclic compounds

These are my notes from lecture 8 of Harvard’s Chemistry 20: Organic Chemistry course, delivered by Dr. Ryan Spoering on February 13, 2015.

Conjugation

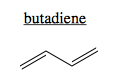

Conjugation refers to π systems involving >2 atoms. The simplest conjugate is butadiene. It has a single π system consisting of four pi electrons, one from each of the four carbons.

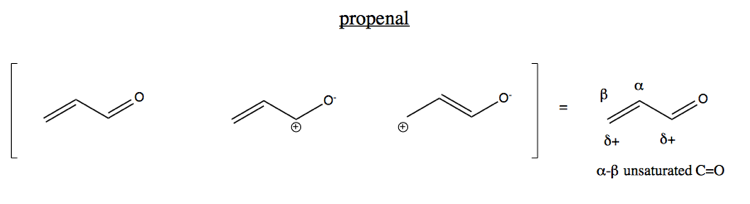

Today we’ll focus on the case of an alkene conjugated to a carbonyl. The simplest example is propenal (also known as acrolein). Because of the electron-withdrawing effect of the oxygen, the central carbon has some amount of positive charge. Indeed, the oxygen pulls some electron density all the way through the four-electron pi system towards it, moving the double bond to the center.

Two types of reactions occur with conjugated carbonyls:

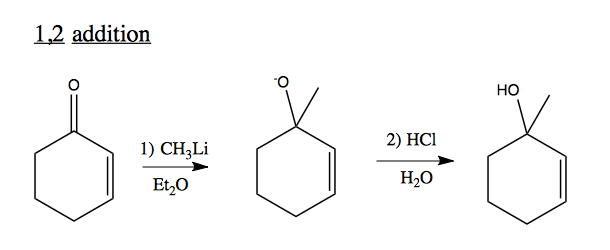

1,2 addition to unsaturated C=O

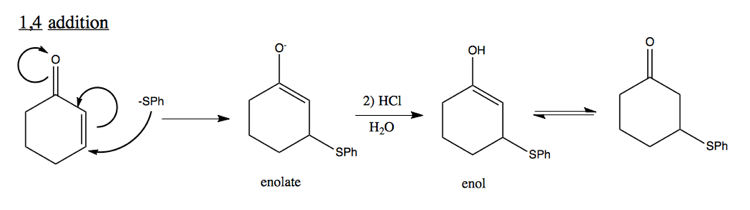

1,4 addition to unsaturated C=O

Note that enol is unstable, and likely to quickly form a carbonyl.

Hard and soft nucleophiles

Metals we think of as “hard” nucleophiles tend to be highly charged and small, and are usually found as oxides in nature. Larger metals like copper and lead are “soft” nucleophiles are usually found in nature as halides or some other form bound to a larger ligand. The formal classification into hard versus soft is as follows:

- Hard are charged, highly electronegative, basic in a Bronsted-Lowry sense - they react with hydrogen, which is a very small, charged electrophile. They tend to prefer 1,2 addition when reacting with a conjugated carbonyls. Examples include HO-, RO-, R-MgBr, R-Li.

- Soft have a “polarizable” electron cloud. They are in the ≥ 3rd row of the periodic table. They tend to prefer 1,4 addition when reacting with conjgated carbonyls. Examples include I-, RS-, R2S-, and π nucleophiles.

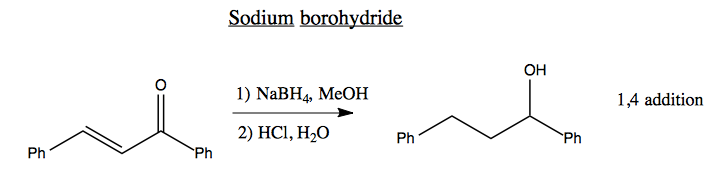

Sodium borohydride is a hard nucleophile. If you react it with this molecule, it will perform 1,4 addition, reducing both double bonds.

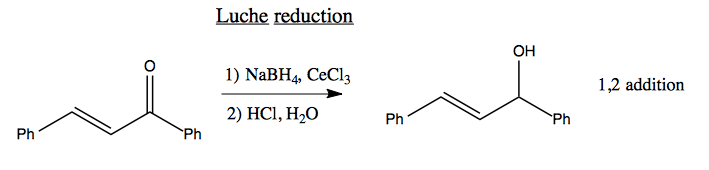

A Luche reduction is the same, but using CeCl3 which for unknown reasons causes only partial reduction, so you end up with 1,2 addition.

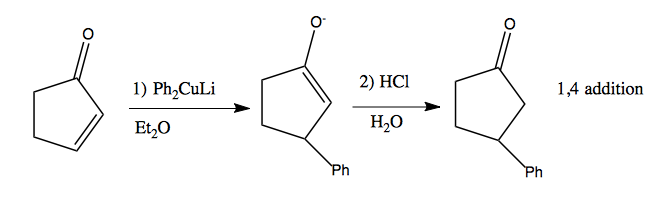

Copper is a soft nucleophile. Organocuprates can be used for 1,4 addition. For instance, R2CuLi is called a Gilman cuprate, and here is how to make it:

2 R-Li + CuBr → R2CuLi + LiBr

In fact, this equation is a simplification, as in solution these actually form aggregates.

Simple Gilman cuprates are available commercially, such as lithium diphenyl cuprate. Here’s what it can do:

Conformational analysis

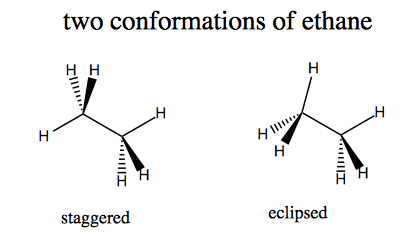

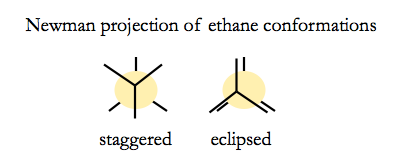

Ethane can have two conformations.

Newman projections are visualiations looking down the C-C bond axis.

The staggered conformation is more energetically favorable, by a surprisingly large margin. Hydrogen is small enough that steric clash does not play a large role in the energetics - it is more about electron density.

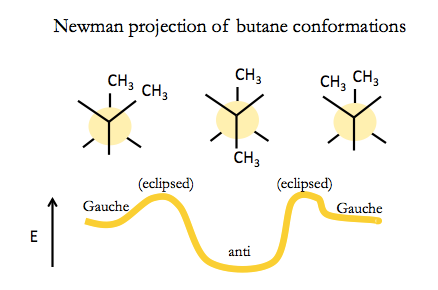

For butane, there are two different types of staggered conformation: staggered anti, and staggered Gauche. Staggered anti is more favorable. To interconvert between anti and Gauche you have to go through an eclipsed conformation. The barrier to this is not so large, so organic molecules like butane actually interconvert all the time, though they send more time in anti.

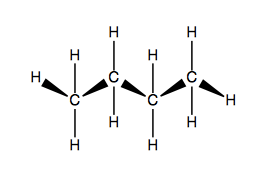

In diamond lattice representation, you orient the molecule so that the main chain itself is undulating in and out towards you. For instance, butane:

This is also a way that you can draw cyclohexane. In fact, if you take the idea of cyclohexane and then just keep substituting methyl groups for each hydrogen recursively, that is the structure of diamond.

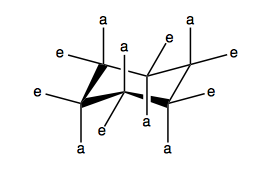

Cyclobutane is not actually flat, it is “puckered”. The four carbons are not coplanar, because if they were, all of the hydrogens would be in an eclipsed conformation. Bending the carbon square relieves that. Cyclobutane is, however, a strained conformation. Cyclopentane is not flat either, it is known as an “envelope” conformation where four carbons are coplanar and one bends downward like the flap of an envelope. This allows staggering the hydrogens on that and the two adjacent carbons, even though the other two carbons will still have eclipsed hydrogens. Cyclopentane has almost no strain. Cyclohexane is completely staggered. It has “axial” and “equatorial” hydrogens. The axial stick straight up and down, and the equatorial are parallel to the nearest C-C bond.

Cyclohexane can undergo a “chair flip” to change between its two conformations. Boat is less stable.

Different substituent groups have different energetic preferences for being in axial versus equatorial positions on cyclohexane. Methyl is found about 95% in equatorial, and only 5% in axial positions. Tert-butyl is about 99.9% in equatorial, only 0.1% in axial. The preferences arise from steric collisions. If a methyl is in an axial position, its hydrogens can interact with the hydrogens in other axial positions, in what are called “1,3 diaxial interactions”. Like Gauche interactions, these are unfavorable and must be minimized. For tert-butyl, these interactions are simply intolerable. Being in the equatorial position allows a group to have all the space it needs.

In cyclohexanes with multiple side chains, groups will have to fight it out for who gets to be equatorial, since even if the two groups are on different carbons, the overall confomation of the cyclohexane determines their axial vs. equatorial position. When a tert-butyl is on a cyclohexane, that cyclohexane is said to be “locked”, as it cannot undergo chair flips. There are two different ways to fuse two cyclohexanes to each other to make decalin, and they have different consequences. Trans-decalin is locked, while cis-decalin is not locked.