Organic chemistry 12: SN2 substitution - nucleophilicity, epoxide electrophiles

These are my notes from lecture 12 of Harvard’s Chemistry 20: Organic Chemistry course, delivered by Dr. Ryan Spoering on February 27, 2015.

SN2 substitution

SN2 are single-step reactions with direct displacement of the leaving group. Because these do not rely on cations, which form under only certain conditions, SN2 are much more diverse than SN1 reactions and are useful in a wide range of synthesis.

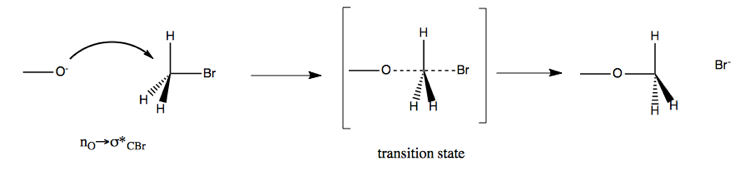

Here is an example:

This has a rate of k[CH3O-][CH3Br], in other words, it is proportional to the concentration of both reactants. The reaction results in stereochemical inversion at the carbon.

Substrates have the opposite preference for participating in SN2 as they do in SN1. Methyl groups are the most likely; the more substituted the carbon is, the less likely it is to participate in SN2, due to steric hindrance of the substituted groups preventing then from flipping inside out. A triply substituted carbon will never participate in SN2. To be an SN2 substrate, it helps to have electron-withdrawing groups (such as Br above). You want polar, aprotic solvents such as acetonitrile (CH3CN), DMF (Me2NCOH), or DMSO.

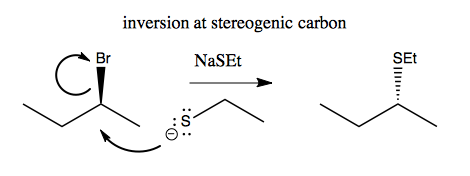

Here’s an example of how you get inversion at the stereogenic carbon:

But note that it’s not always as simple as changing a wedge to a dashed wedge. Sometimes, especially for cyclic molecules, it is much more complicated.

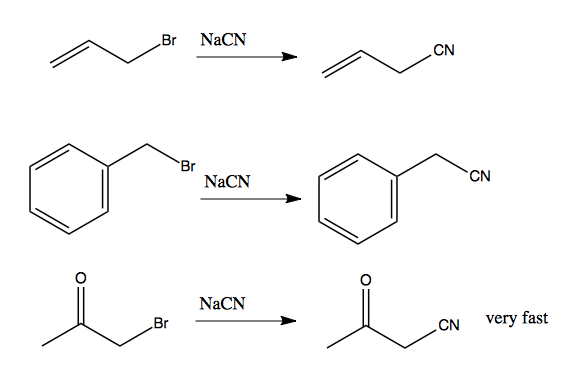

As noted above, substrates are more likely to undergo SN2 if they have an electron withdrawing group. A nearby conjugated (pi) system nearby can enhance the effect of an electron withdrawing group. For instance, if you have a halide in an allylic or benzylic position, these reactions are quite favorable. The third reaction here is very fast:

Note that because CN- is a competent nucleophile, it will trigger an SN2 reaction. Thanks to the pi system, the substrates at left would eventually undergo SN1 in the right solvent (perhaps ethanol) but this would take a very long time. These reactions are much faster, suggesting they proceed almost entirely by SN2.

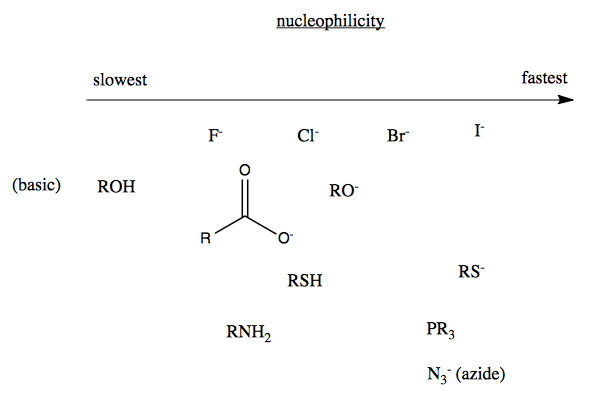

Nucleophilicity

The rate of these reactions is determined not only by the suitability of the substrates (discussed above) but also the strength of the attacking nucleophile. In a seeming paradox, iodine is both a good leaving group and a good nucleophile. This paradox is explained by the hard vs. soft nucleophile distinction.

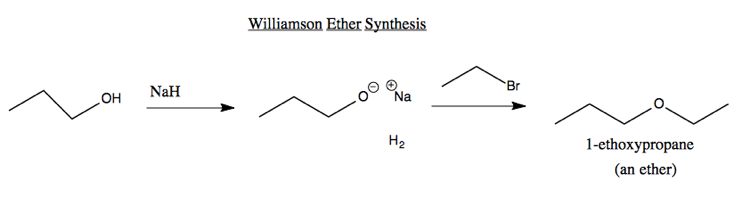

Ether synthesis

The simplest reaction to have its own name is the Williamson Ether Synthesis. You react an alcohol with sodium hydride. Hydrogen gas bubbles out, leaving a sodium alkoxide. When this is then reacted with an aklyl halide, you get an ether. For instance:

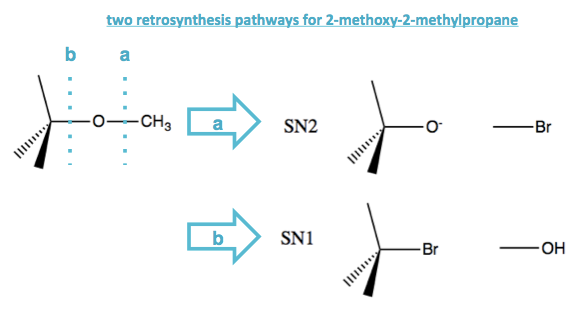

Thinking retrosynthetically, suppose you wanted to get the ether compound 2-methoxy-2-methylpropane, which has a tert-butyl on one side and a methyl on the other side of the O. You could do this via SN2 or SN1, taking advantage of either how good an SN2 substrate CH3Br is, or how good a SN1 substrate tert-butyl-bromide is.

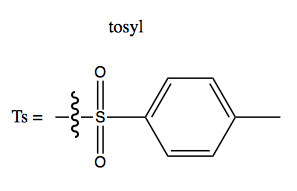

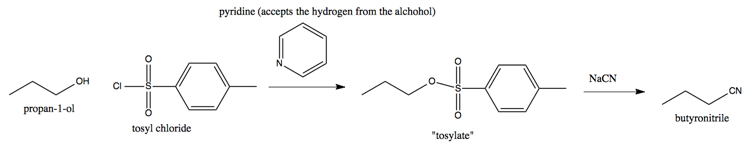

Making alcohols a leaving group with tosylates

A tosyl (Ts) group is this:

Suppose you have an alcohol (-OH) that you want to remove. Pyridine can accept the H+, and a tosyl can steal the O-. For instance, here’s how you can use tosyl chloride and pyridine to get from propanol to butyronitrile:

This reaction proceeds becasue the tosylate, which has as its R group the oxygen that used to belong to the alcohol, is a good leaving group.

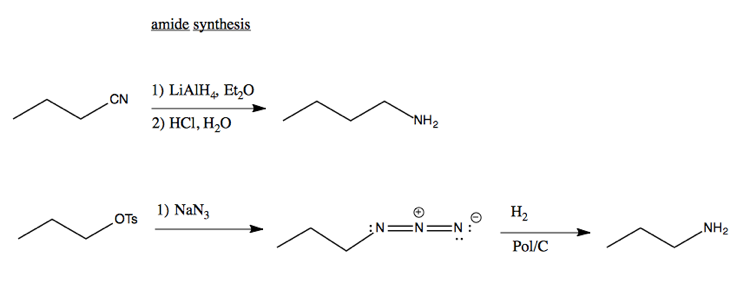

Synthesis of amides

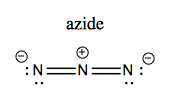

You can synthesize amides using either LiAlH4 or azides. Azide (N3-) is linear and looks like this:

Here’s examples of synthesizing amides via SN2 reactions:

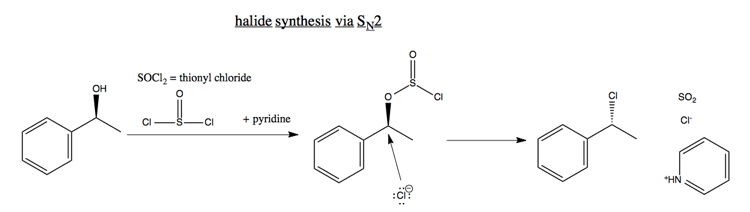

Synthesis of halides

SN2 can also be used to make halides from alcohols, for instance:

The inversion of stereochemistry in this reaction is extremely reliable, which is a useful property.

Epoxides

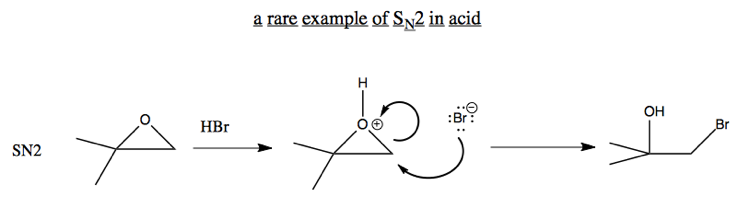

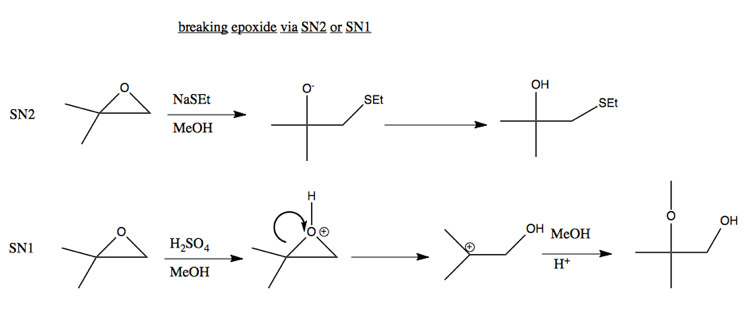

In general, O- is not a good leaving group. However, an exception is if you have compensation thanks to breaking a strained ring. For example, breaking this epoxide can be achieved via either SN2 or SN1:

Ordinarily, SN2 don’t happen in acid, because the nucleophile would just get protonated. But here is an exception: