Organic chemistry 18: Electrophilic addition to alkenes

These are my notes from lecture 18 of Harvard’s Chemistry 20: Organic Chemistry course, delivered by Dr. Ryan Spoering on March 13, 2015.

Hydrohalogenation

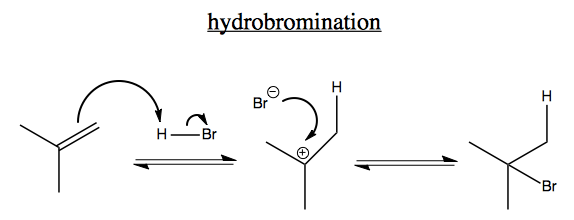

The above process is called Markonikov addition. It is the reverse of E1 and it forms the most stable cation, i.e. the halogen ends up on the most substituted carbon. There are also reactions where the halogen ends up on the least substituted carbon (not shown), and those are called non-Markonikov.

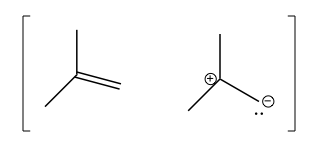

In general, in alkenes, there is some amount of skewing of electron density towards the primary carbon rather than the tertiary carbon, i.e. there exists the following resonance structure:

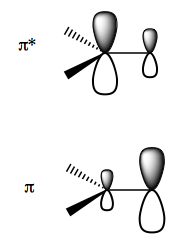

To think about this in terms of frontier molecular orbital theory, the electron density of the π orbital is skewed towards the primary carbon, while that of the π* anti-bonding orbital is skewed toward the tertiary carbon:

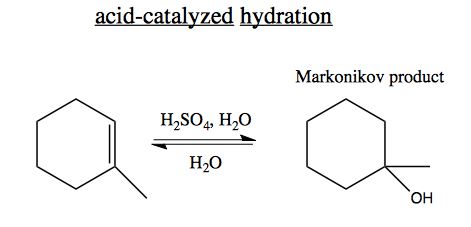

In acid-catalyzed hydration, the following reaction is reversible. We can make it run forward through using H2O as solvent, so it is in excess. The alcohol (product) is enthalpically (ΔH) favored, while the alkene and H2O (reactants) are entropically (ΔS) favored. Therefore high temperature will make the reaction run in reverse.

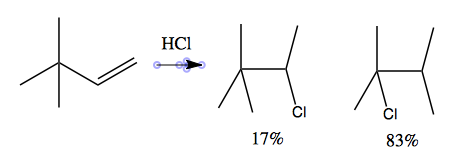

In some cases, multiple products are possible:

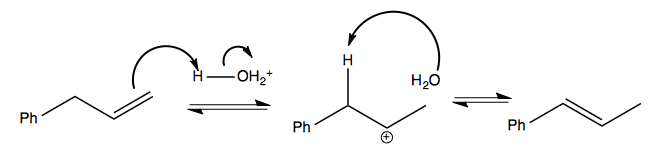

And in some cases you can get a rearrangement of double bonds without losing or gaining any:

Dihydrogen addition

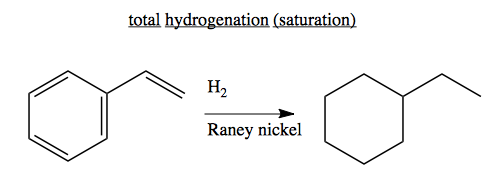

Before spectroscopy, one way of trying to figure out a molecule’s structure was to measure how many equivalents of hydrogen it could take on - this led to the term “saturated” to refer to alkenes that have the maximum number of hydrogens.

If you take a Ni/Al alloy and leach out all of the aluminum with NaOH so that you end up with a porous nickel powder, known as Raney nickel. Raney nickel will absorb a huge amount of hydrogen, and it will fully hydrogenate just about anything. The surface area is important for catalysis, but the precise mechanism is not fully known. It is a very harsh catalyst, and will not only saturate away double bonds, but will often also break C-X, C-S and C-C bonds by adding hydrogen in - a process called “hydrogenolysis”.

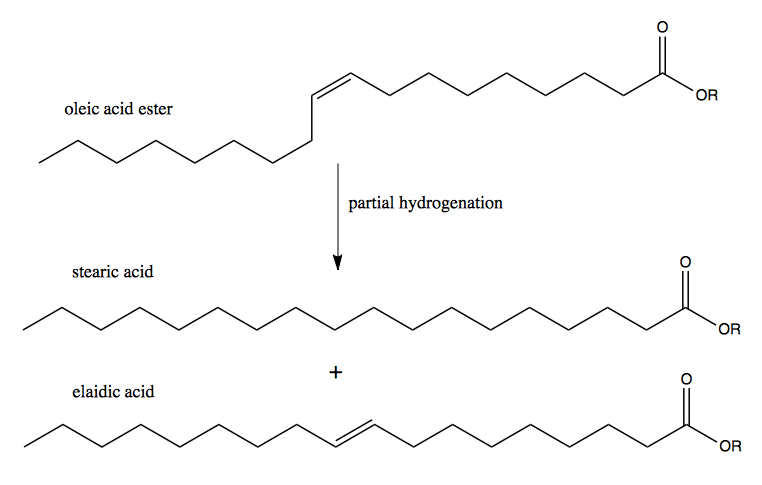

Oleic acid, like all naturally occurring fats, is a cis fat. Partial hydrogenation will yield a mixture of stearic acid (fully hydrogenated) and elaidic acid (a trans fat), both of which spoil less readily than oleic acid. This mixture is what has been marketed as margarine.

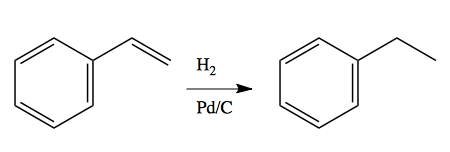

Palladium is the most useful catalyst for selective hydrogenation of alkenes. Unlike Raney nickel, it will never break sigma bonds between C-X, C-S or C-C, and it will not hydrogenate ring systems. Palladium is used in the form of “palladium on charcoal” or Pd/C. As with Raney nickel, the suspension of the palladium onto the porous charcoal surface allows it to acquire a large amount of surface area.

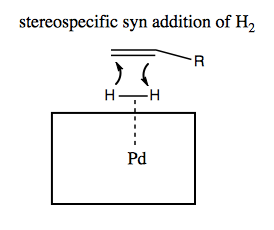

The way it works is that H2 coordinates to the palladium on the surface, and then when a double bond comes by, the H2 has stereospecific access to one face of it:

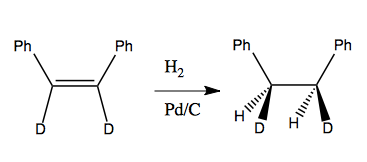

Here is an example of that stereospecificity:

Halogen addition

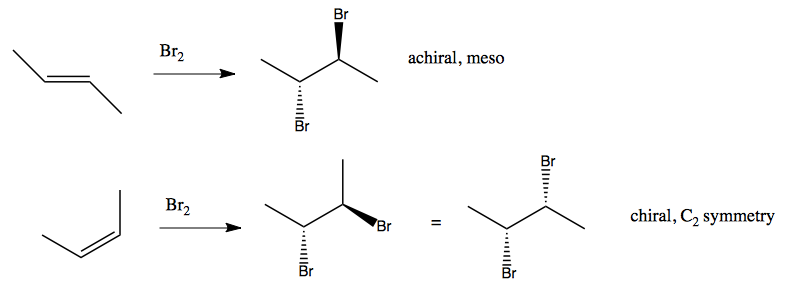

In some instances, the cis-trans isomerism of the original alkene determines how halogens get added:

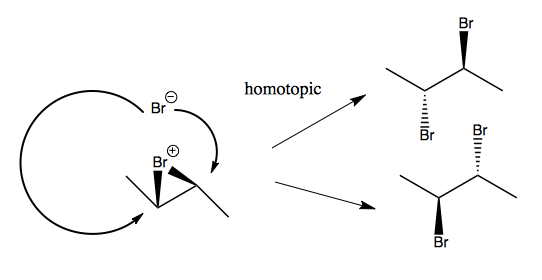

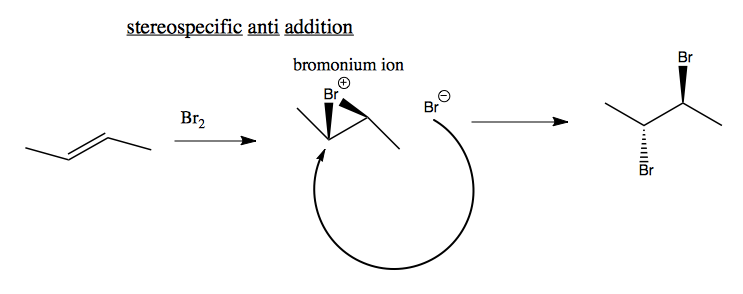

You can also do stereospecific anti addition, where the two bromines add in anti positions. This reaction exhibits absolute stereospecificity, which provides evidence that a carbocation is not formed. If a carbocation were formed, it would not be stereospecific. Instead, it is the case that one bromine simultaneously binds to two carbons, creating a bromonium ion, which the other bromine then attacks.

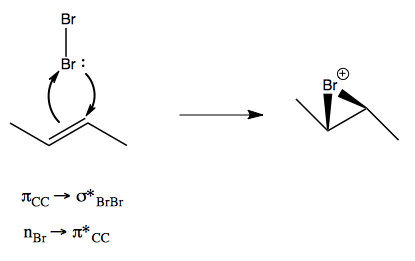

The mechanism of bromonium ion formation is actually that two orbital exchanges occur simultaneously:

The second Br- can actually attack either carbon, but it turns out these two possibilities are homotopic, as the two products shown at right are actually the same molecule just rotated 180°.