Organic chemistry 29: Aromaticity - nucleophilic aromatic substitution, benzyne

These are my notes from lecture 29 of Harvard’s Chemistry 20: Organic Chemistry course, delivered by Dr. Ryan Spoering on April 20, 2015.

Nucleophilic aromatic substitution

Last time, we discussed aromatic reactions with electrophiles, which are very common reactions. Today we discuss aromatic reactions with nucleophiles, in which the aromatic acts as an electrophile. These are much rarer.

With electron-withdrawing groups

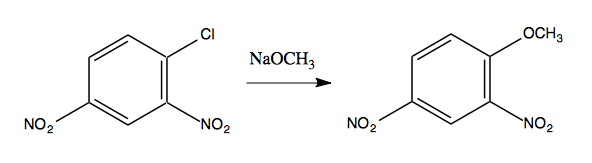

A classic example is as follows:

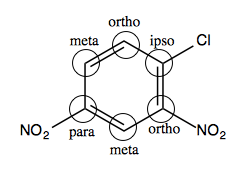

In the aryl halide at left, the carbons should be named relative to the chloride:

The chloride itself is the “ipso” position, so swapping out -Cl for -OCH3 is an ipso substitution.

If you think through the mechanism of this, at first it doesn’t make sense:

- It can’t be an SN2 reaction, because if you imagine the CH3O- ion as a nucleophile, it would have to attack the ipso carbon, and we’ve never had an SN2 reaction with an sp2 hybridized carbon.

- It can’t be an SN1 reaction, because for the Cl to depart, leaving behind a carbocation, would involve having a positive formal charge at an sp2 hybridized carbon, which again is not something that happens. Moreover, such an SN1 reaction would be very slow, but the reaction in question is actually fast.

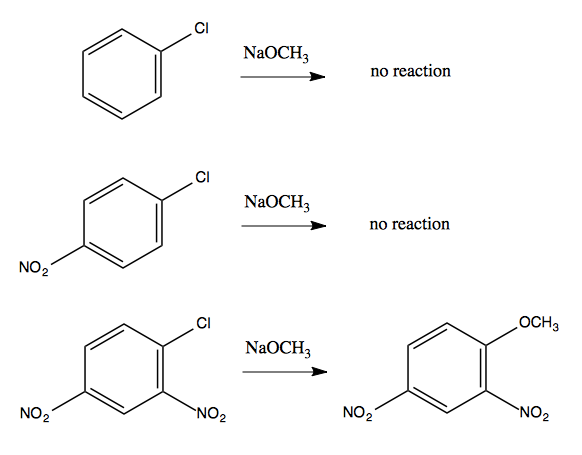

But some insight can be gained by noticing that the reaction will not happen without the NO2 electron-withdrawing groups:

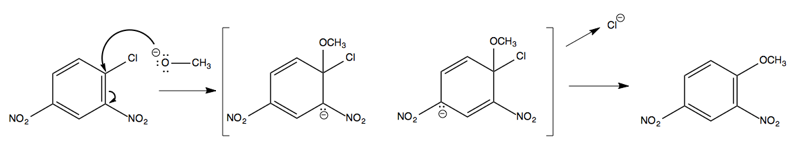

It turns out that CH3O- does indeed attack at the ipso carbon, but in the intermediate, the CH3O and the Cl are both bound at once:

The resonance structures in the intermediate provide enough stabilization to make this possible. In general, having two ortho-, para-directing, electron-withdrawing groups in the reactant is sufficient to allow this sort of reaction to occur.

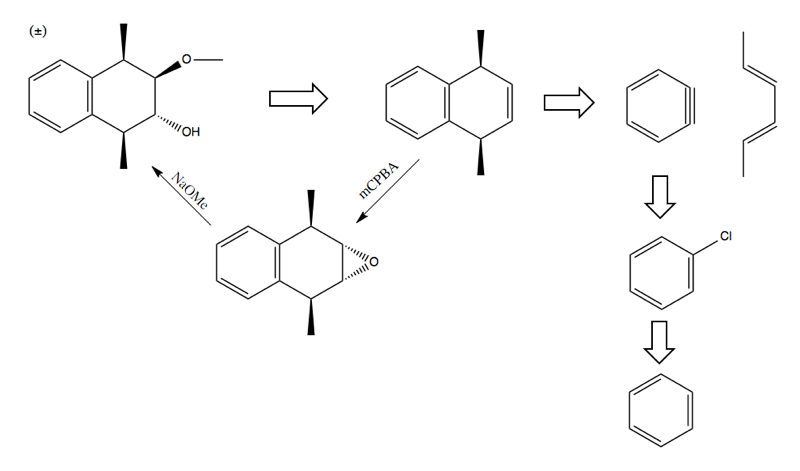

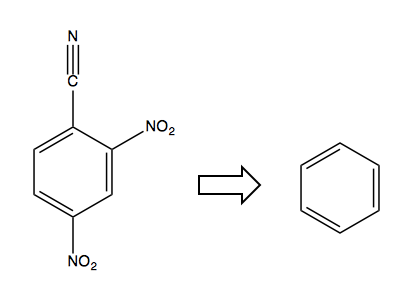

Now consider this retrosynthesis problem:

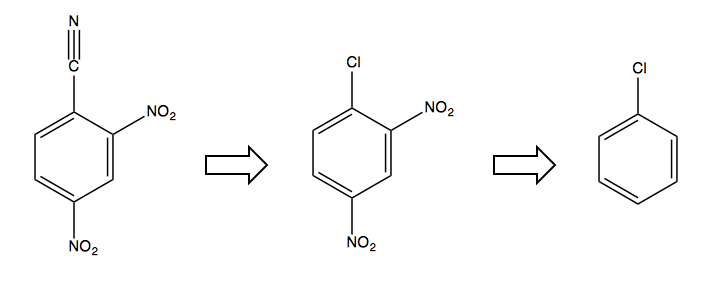

The only solution is to first start with a halogen in the desired ipso position, as it is an ortho-, para-director and will allow you to add the NO2 electron-withdrawing groups, after which you can swap out the Cl for the CN:

Note that the larger halogens Br and I don’t participate as well in this chemistry. F is actually better than Cl as a leaving group for this sort of substitution, however we do not know how to make fluorinated benzene, so here our only option was to use a chlorinated one.

With benzyne

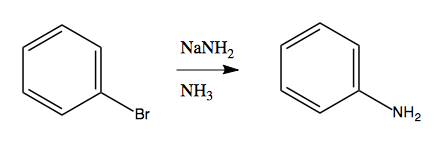

Now consider this reaction:

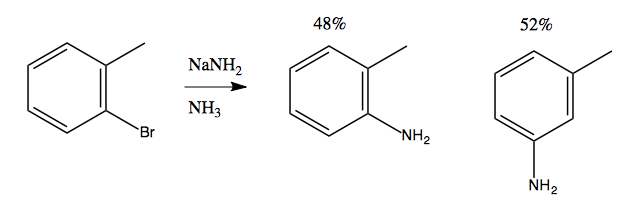

At first it seems to violate the rule we have just learned, that you need electron-withdrawing groups to enable nucleophilic aromatic substitution. But we can gain some insight by noticing that if we do this with an extra methyl group, we get an almost 50/50 mix of meta and ortho products:

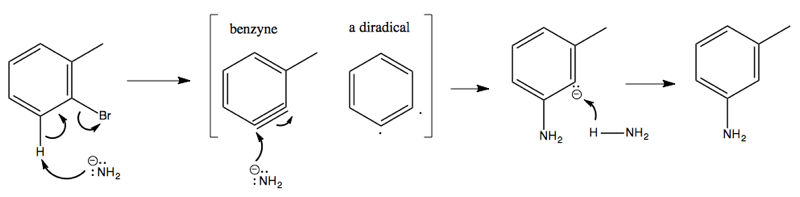

Considerable evidence indicates that this reaction involves NH2- attacking and stealing a hydrogen, almost like an E1 reaction, creating a weird and reactive intermediate called benzyne. This is then attacked a second time by an NH2- that binds, resulting in a carbanion as the second intermediate. Finally, this gets protonated using a proton from an NH3, yielding the product:

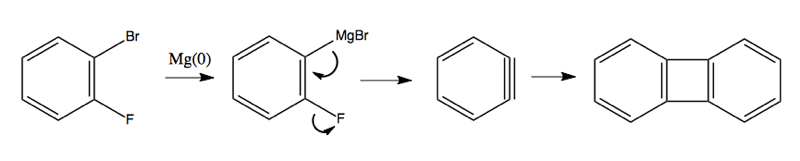

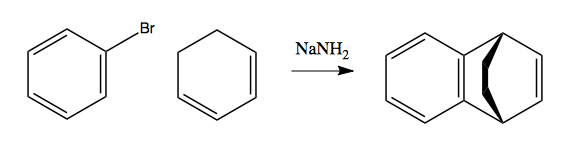

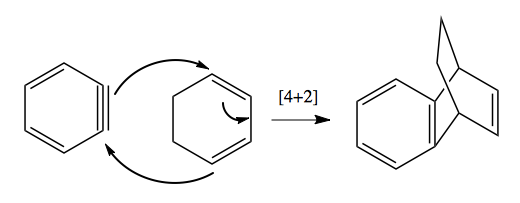

Here are some more crazy reactions involving benzyne as an intermediate:

This last reaction has the following mechanism:

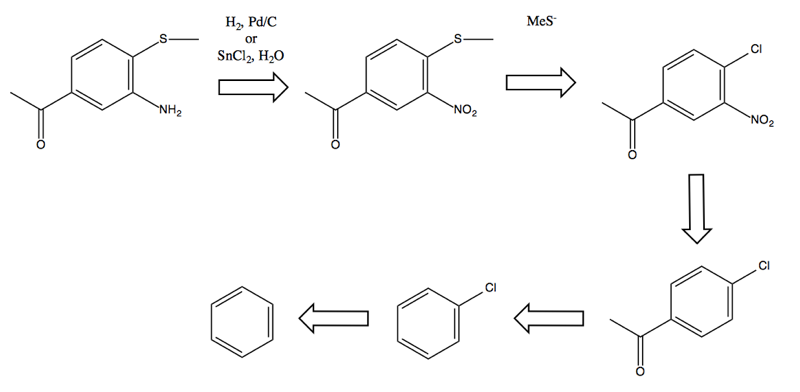

Retrosynthesis practice problems

Using the aromatic chemistry we’ve learned in this class, you should be able to solve the following problems.

Problem 1

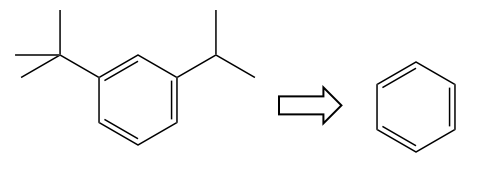

Problem:

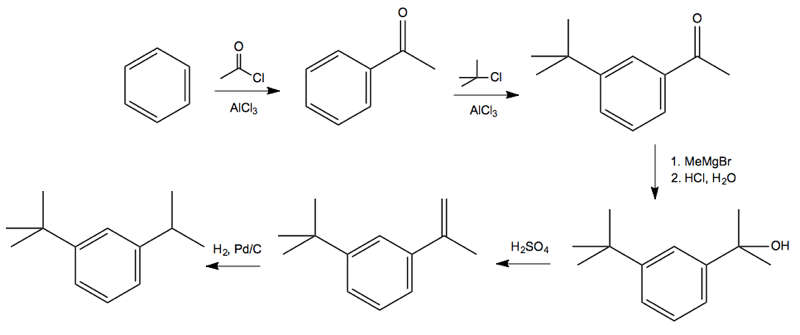

Solution:

Problem 2

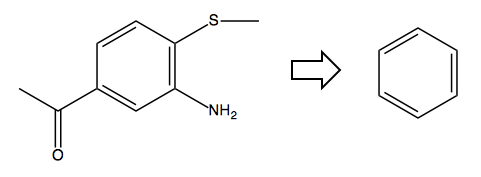

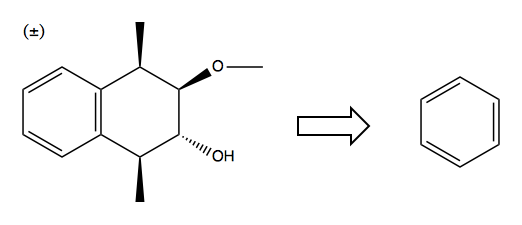

Problem:

Solution:

Problem 3

Problem:

Solution: