Organic chemistry 32: NMR spin-spin coupling

These are my notes from lecture 32 of Harvard’s Chemistry 20: Organic Chemistry course, delivered by Dr. Ryan Spoering on April 27, 2015.

This lecture relies heavily on slides. With Dr. Spoering’s permission, I have uploaded a scan of today’s handout here.

Chemical shift equivalence

We continued to go over the practice spectra from last time. A few general lessons regarding chemical shift equivalence:

- In alkanes longer than ethane, not all hydrogens are chemical shift equivalent - the CH2 hydrogens are different from CH3 hydrogens.

- On cyclohexane, all hydrogens are equivalent. This is because even though axial and equatorial hydrogens are in different environments, the chair flip is sufficiently rapid that the hydrogens are considered to be “exchangeable in some rapid chemical process”, thus meeting the third criterion from lecture 31

- In N,N-dimethylacetaminde, whether two methyls are equivalent depends upon temperature - only at high temperatures does the thermal energy overcome the rotational barrier, making them equivalent.

Spin-spin coupling

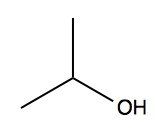

Consider isopropanol.

We have three peaks:

- δ 4.0, integration 1H = the hydrogen on the central carbon. It appears as a “multiplet” with many tiny peaks very close in energy.

- δ 2.5, integration 1H = the alcohol hydrogen. It appears as a “doublet” with two peaks very close in energy.

- δ 1.2, integration 6H = the hydrogens on the distal carbons. It appears as a “doublet” with two peaks very close in energy.

The multiplet and doublets are the result of spin-spin coupling. Here is a simpler generalized example:

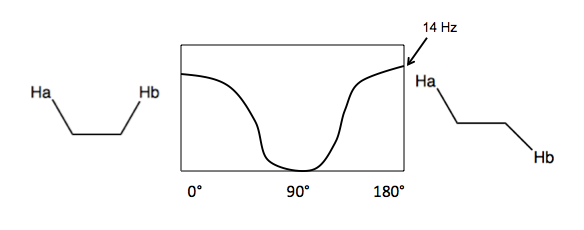

Here, Hb can have spin of either {+½, -½}, so it splits Ha by J Hz. J is not joules, apparently, but rather a variable indicating the coupling constant in units of Hz. The formula is J (Hz) = H (ppm) × B0 (MHz), where B0 is magnetic field strength.

There are two ways that spin-spin coupling can arise:

- Vicinal (3-bond) coupling. Here, the two hydrogens are near each other but not on the same cabron, and freely rotating. J depends on the angle between them, with a max of 14 Hz. The average J is 7-8Hz.

- Geminal coupling. This occurs when two hydrogens are bound to the same carbon. Most of the time, hydrogens bound to the same carbon are homotopic or enantiotopic and thus chemical shift equivalents, so you get no spin-spin coupling. The only case where you get geminal coupling is if the hydrogens are diastereotopic.

With this in mind, if we look again at the isopropanol 1H NMR spectrum, we can see that:

- HA is doublet by HB

- The 6 HC are doublet by HB

- HB is doublet by HA and 6-plet by HC.

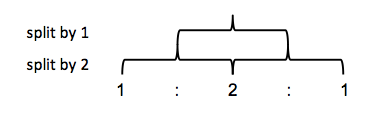

You can make tree diagrams to see how splitting occurs. In ethanol for example, let’s call the CH3 hydrogens HA and the CH2 hydrogens HB. A single HB hydrogen would split the HA signal into a 50/50 doublet. Two HB hydrogens split it a second time, but instead of four equally likely outcomes you get three outcomes with probability 25/50/25, thus you see a higher middle peak.

This ends up being Pascal’s triangle. Thus, a 1:1 doublet means you’re adjacent to an atom with one hydrogen bound. A 1:2:1 triplet means you’re adjacent to CH2. A 1:3:3:1 quadruplet means you’re adjacent to CH3.

In isopropanol, HB is split six times by HC for a septet. Rows of Pascal’s triangle can be calculated quickly using the choose function, so a septet is (in R):

> choose(6,0:6)

[1] 1 6 15 20 15 6 1

But then in addition to the 6 HC, HB is also being split by HA, so HB ends up being a doublet of septets, better known simply as a multiplet.

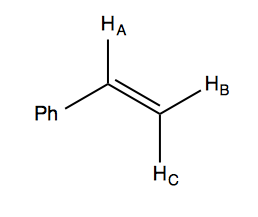

With this in mind, we can look at the NMR spectrum of styrene in the handout. It has a 5:1:1:1 integration ratio. The total of five ortho, meta, and para hydrogens are not chemical shift equivalents, which is why the 5H peak at far left appears as multiple peaks. Of the remaining three hydrogens in the molecule, we have a doublet-of-doublets at δ ~6.7 (all four peaks are approximately equal 1:1:1:1, which is how you can tell it is a doublet of doublets and not a 1:3:3:1 quadruplet), and then two doublets at δ ~5.7 and ~5.2. Here is a diagram of the molecule:

HA is split twice, by HB and HC, hence it is the doublet-of-doublets. Note that HB and HC are each split just once, by HA; they do not split each other (because they are homotopic or something?).

To make matters more complicated, each of what appears to be a single peak within a doublet in the styrene spectrum actually has two mini-peaks if you zoom in really close on the peak. We’ll talk about why that is next time.

This discussion of spin-spin coupling is continued in lecture 33.