Chemical biology 05: Using small molecules to understand life processes

These are my notes from lecture 5 of Harvard’s Chemistry 101: Chemical Biology Towards Precision Medicine course, taught by Dr. Stuart Schreiber on September 17, 2015.

This lecture will represent a shift to the study of dynamic information flows, as opposed to static ones. We will talk about the use of tool compounds to understand biological processes. For now we’ll talk about these without any discussion of where these molecules come from, or how their mechanisms of action became known. The next lecture will touch on those issues.

Key points for today:

- Small molecule probes provide a way to understand a protein’s function in a living cell.

- Whereas genetic variants can cause constitutive, heritable changes to protein function, small molecules cause reversible, non-heritable changes.

Most new technologies have an initial wave of hype, then disappointment, and then recover a more sober expectation of what they can accomplish. In the heyday of RNAi, there was a review on the limitations on the technology [Kaelin 2012]. We can expect a similar reassessment of CRISPR/Cas9 in due time. There has similarly been new perspective on chemical probes - today’s readings include a number of commentaries on this topic [Schreiber 2009 , Prince & Ahn 2010, Workman & Collins 2010, Arrowsmith 2015].

It is important not to assume that genetic and small molecule perturbations will always give identical results. Here are some cautionary tales:

- Calcineurin. Mice have two genes that encode nearly identical calcineurin proteins. Only when both are knocked out do you see phenocopy of the effects of small molecule inhibition of calcineurin.

- mTOR. mTOR can be a part of either of two complexes, mTOR1 and mTOR2. Some inhibitors only bind it when it is part of mTOR1.

- HDAC6. HDAC6 has two domains, only one of which is inhibited by a probe; obviously, genetic knockout deletes both.

- The proteasome. The proteasome has three catalytic domains (trypsin-like, chymotrypsin-like, and PHGH-like. Genetic deletion eliminates all of them; small molecule proteasome inhibitors only inhibit one or two of them.

- STK33. It was reported that whenever cancers have KRAS mutations they become dependent on what is otherwise a housekeeping protein, STK33. Knockout of STK33 can inhibit these cells’ growth. The science there is sound. Yet, for reasons not yet elucidated, small molecule inhibition of STK33 doesn’t achieve the same effect.

- PKC. This is an example of dependence on cellular context. Small molecule inhibition of PKC ablates its function unless the cell expresses an adaptor protein called AKAP79, which allows PKC to function even when bound by the small molecule.

- PDK1. Similar to the situation with PKC. An inhibitor works only when an adaptor protein PKCβII is absent.

The case study for today revolves around the cell cycle. An overarching theme is that most of our knowledge of how the cell cycle normally works has come from studies of what happens when the cell cycle is broken in cancer.

In the early days when the cell cycle was first beginning to be understood, people referred to the groove on the cell surface that forms as cytokinesis begins as the “furrow”. It was known that actin was involved, but no one knew what forces were acting to cause it to contract and split the cell.

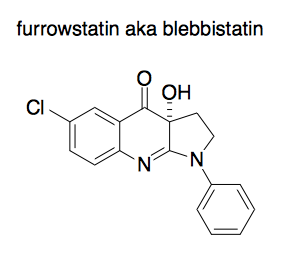

Insights were gained through the use of a tool compound called furrowstatin or blebbistatin. This compound was originally purchased from a commercial vendor. However, when people synthesized it fresh, they found it lacked its originally reported biological activity. But if they let the newly synthesized batch sit on the bench for a while and then try again, it started to work. Turns out, it was oxidizing, and the oxidized product was the active one. This kind of thing happens all the time - see Derek Lowe’s post from yesterday. When people draw furrowstatin, they still draw the un-oxidized version:

Anyway, what the oxidized product does is to stop the process of cytokinesis in place. So you can freeze frame the process of cytokinesis at any timepoint where you add a drop of the compound. If you wash it out, cytokinesis picks up where it left off.

The mechanism of action turns out to be that furrowstatin binds a protein called non-muscle myosin II. This showed that this motor protein is involved in cytokinesis, but is not involved in sister chromatid separation, since that process could continue in the presence of furrowstatin.

Once this was known, people started staining for non-muscle myosin II, and found that it co-localized with actin during cytokinesis. Then they stained for other things and found that anillin co-localized with actin as well, suggesting it might also be involved.

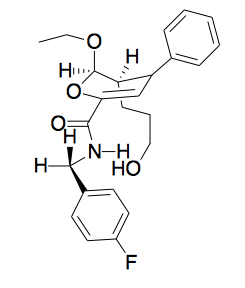

A phenotypic screen revealed a second tool compound, which caused a phenotype never before seen in nature: it made segregating chromosomes and microtubules explode into an astral shape, with the centromeres at the center. How would you ascertain that this compound isn’t just behaving in a non-specific way like a detergent? From a purely chemical perspective, you can tell if the compound is specific by changing the functional groups you think are involved in the activity and seeing if that abolishes activity. If the answer is that you can tweak the molecule any which way as long as the hydrophobicity and other general properties are the same, it’s probably non-specific. If, on the other hand, it has a tight structure-activity relationship, that supports it being specific. In particular, if you flip the chirality or just change one stereocenter, and that abolishes activity, then the compound probably has a specific target. This compound has 3 stereocenters, and therefore 8 stereoisomers. People synthesized 4 of these 8 (Diels-Alder cycloaddition favors endo- over exo-isomers, and there is still no easy way to make the other 4 which are exo-). The 1S enantiomer was orders of magnitude less potent than the 1R.

Turns out the compound was a kinesin-5 inhibitor. Until then, motor proteins were considered undruggable. Since then, people have found small molecules that specifically target other motor proteins — for instance, the small molecule ciliobrevin targets dynein [Firestone 2012].

Kinases, too, were once considered undruggable. But precision medicine demands that we develop selective small molecule probes against targets classically considered undruggable, because these comprise most known disease genes’ products. This is therefore the “chem 101 challenge”.

A note about the “promises and perils” of chemical biology (see today’s readings [Arrowsmith 2015]). An important recommendation is that active probes should always be reported alongside a negative control: a small molecule with the most minor possible chemical modification that abolishes activity.