Introductory prion reading list

Or, “Some papers that shape my thinking on prion therapeutics”.

Lately I’ve gotten a request from several people, ranging from scientists starting to get interested in prions, to people at risk for prion disease starting to get interested in science. People have asked me to put together a suggested reading list to introduce them to the field. I resisted this request for a long time, for a few reasons. First, I like to read and cite exhaustively, not just to pick a few favorites. Second, recommending papers is hard — how much should you prioritize reading the earliest discovery of something versus more recent work that contains more of a full picture? Third and perhaps most importantly, there is no surer way to make enemies than to fail to cite someone’s paper in a list of important milestones in the field!

But eventually enough people asked me that I relented and decided to write this post. But I want to frame it slightly differently. What follows is not intended as a list of the most important papers, but rather, as an annotated guide to how I think about prion therapeutics, with suggested reading along the way. Please don’t be offended if your paper isn’t here — this post absolutely does no justice to the large swathes of the prion field that I personally just don’t spend as much time thinking about, such as neuropathology, prion detection, structural biology, veterinary prions and zoonotic risk, and so on.

Every piece of formal writing that I produce these days (fellowship applications, my preliminary qualifying exam, etc.) contains, usually as the first sentence, a statement something like this:

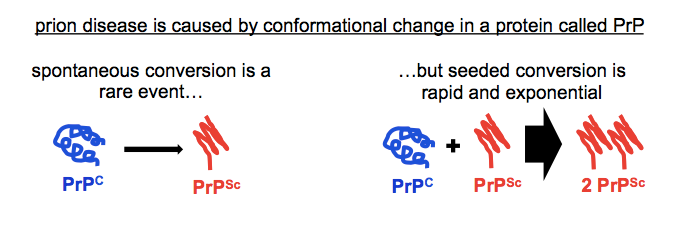

Prion disease is a neurodegenerative disorder caused by misfolding of the cellular prion protein, PrPC, into an autocatalytically self-propagating conformer called the scrapie prion protein, or PrPSc.

That’s the disease mechanism for you, in one sentence. What’s incredible is just how many bothans died to bring us this information. That one sentence contains whole careers, decades of work condensed into a singular conclusion.

If you only care to read one paper about this sentence, read Stanley Prusiner’s Nobel Lecture [Prusiner 1998]. If you do want to read the whole backstory, here are some key points along the road to that one sentence, with the corresponding papers:

- There are transmissible agents that can be inactivated by things that destroy proteins but not by things that destroy nucleic acids, and must therefore be proteinaceous infectious particles: prions [Prusiner 1982].

- Prions can be purified biochemically from infected brains by a many-step process relying on (among other things) their detergent insolubility and protease resistance. The amino acid sequence of the substituent protein can then be read out — this is the first identification of PrP as the constituent of prions [Prusiner 1984].

- PrP is encoded by a chromosomal gene expressed in both infected and uninfected animals — not a viral gene [Oesch 1985, Chesebro 1985].

- The chromosomal PrP-encoding gene in mice is in linkage with a gene determining prion incubation time [Carlson 1986]. In fact, the PrP-encoding gene and the incubation time gene are one and the same [Westaway 1987].

- A genetic prion disease is linked to mutations in the PRNP gene encoding PrP [Hsiao 1989]. (This has since been shown for many other mutations in PRNP, and none in any other gene).

- Hamster PrP transgenes allow mice to be infected with hamster prions. Thus, PrP amino acid sequence is what governs the species barrier (now more often called a transmission barrier) [Scott 1989].

- Homozygous PRNP genotype is a risk factor for sporadic prion disease in humans [Palmer 1991].

- PrP knockout mice are incapable of being infected with prions. They neither propagate prions nor fall ill. Thus, PrP is required for prion replication and disease progression [Bueler 1993].

- PrPC is primarily alpha helical, while PrPSc is primarily beta sheet. Thus, conformational change is a feature of prion conversion [Pan 1993].

- PrPSc does not seem to have any post-translational modifications when compared to PrPC. Thus, prion conversion appears to be strictly conformational [Stahl 1993].

- PrP can be converted to a protease-resistant form in a cell-free reaction, indicating the conformational change results from direct interactions between PrP molecules, rather than being a side effect of some cellular process [Kocisko 1994].

Here’s a quick aside about nomenclature. Along the way as you read these papers, you’ll notice there are a ton of different names for prion disease. In humans, some of these names refer to different clinical presentations, others to specific strains or genetic mutations or etiologies. Most of these names originated by accident of history, and while they are not totally meaningless, they in no way represent any sort of logical or systematic organization of prion disease subtypes that one would generate from first principles knowing everything we know today. And then in non-human mammals, people just call all prion disease in that animal one thing, even though other animals, like humans, have multiple strains and multiple etiologies of prion disease. The naming system is a mess, which is why I almost exclusively use the term “prion disease”.

| species | name |

|---|---|

| human | Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease fatal familial insomnia Gerstmann-Straussler-Scheinker disease variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease kuru Huntington disease-like 1 variably protease-sensitive prionopathy PrP cerebral amyloid angiopathy PrP systemic amyloidosis |

| sheep and goats | scrapie |

| deer, elk, and other cervids | chronic wasting disease |

| cattle | bovine spongiform encephalopathy |

| any | transmissible spongiform encephalopathy |

Table 1. Other names for prion disease

Now, moving beyond that one first sentence, the next key fact to know is the existence of prion strains. My applications and such often have a second sentence somewhere in there that goes like this:

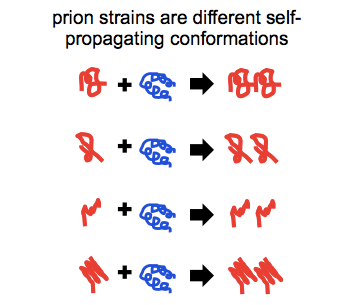

Prions exist in phenotypically diverse strains, which are encoded in distinct conformations of PrPSc.

So you see, there’s actually an error in the first sentence at top. When I said “an autocatalytically self-propagating conformer called… PrPSc” what I really meant was “any of a variety of autocatalytically self-propagating conformers, all of which can be referred to as PrPSc”.

Prion strains have been defined operationally by a range of features: differences in incubation times, transmission properties to different species, neuropathological profiles and attendant symptomatic presentations, protease sensitivities and cleavage sites, and sensitivity to inhibition by small molecules. But at the root of all of these phenotypic differences, we believe that what prion strains are is different conformations of PrPSc.

How do we know? We still don’t know the structure, at atomic resolution, of any prion strain. But there is ample indirect evidence that strains differ in conformation. Here are three of the most classic demonstrations of it:

- The distinct protease cleavage sites of different prion strains are maintained upon cell-free propagation of prions. Thus, the cleavage sites are a property of PrP itself and not of the intact cell [Bessen 1995].

- Different genetic mutations in PRNP give rise to different protease cleavage sites and different neuropathological profiles, and these differences are maintained upon passage into mice lacking the original mutations. Thus, conformation alone, without any difference in amino acid sequence, is sufficient to encode these strain differences [Telling 1996].

- An epitope that is exposed in PrPC but buried in PrPSc can be used to distinguish the two isoforms. Using this method it is shown that different prion strains differ in their conformational stability (resistance to guanidine denaturation) [Safar 1998]. As an aside, this paper is also a landmark for demonstrating the existence of protease-sensitive prions.

All the references I’ve cited so far have probably already convinced you that PrP is everything in prion disease. PrP is the pathogen, its conformation is what creates infectivity and defines strain, it is what governs incubation time and species barriers, it is what causes genetic prion disease. Every approach — biochemistry, model organism genetics, human genetics — converges on this one answer: PrP is what causes prion disease.

And all of that means that PrP is the obvious drug target if you want to treat prion disease. So I often also include a sentence or two along these lines:

From first principles, PrP is the obvious drug target for treating prion disease. PrP is the major or sole component of prions, and its expression is required for disease and for neurotoxicity.

Here are a few of the foundational papers that provide proof of principle that if you can target PrP, then you can treat prion disease:

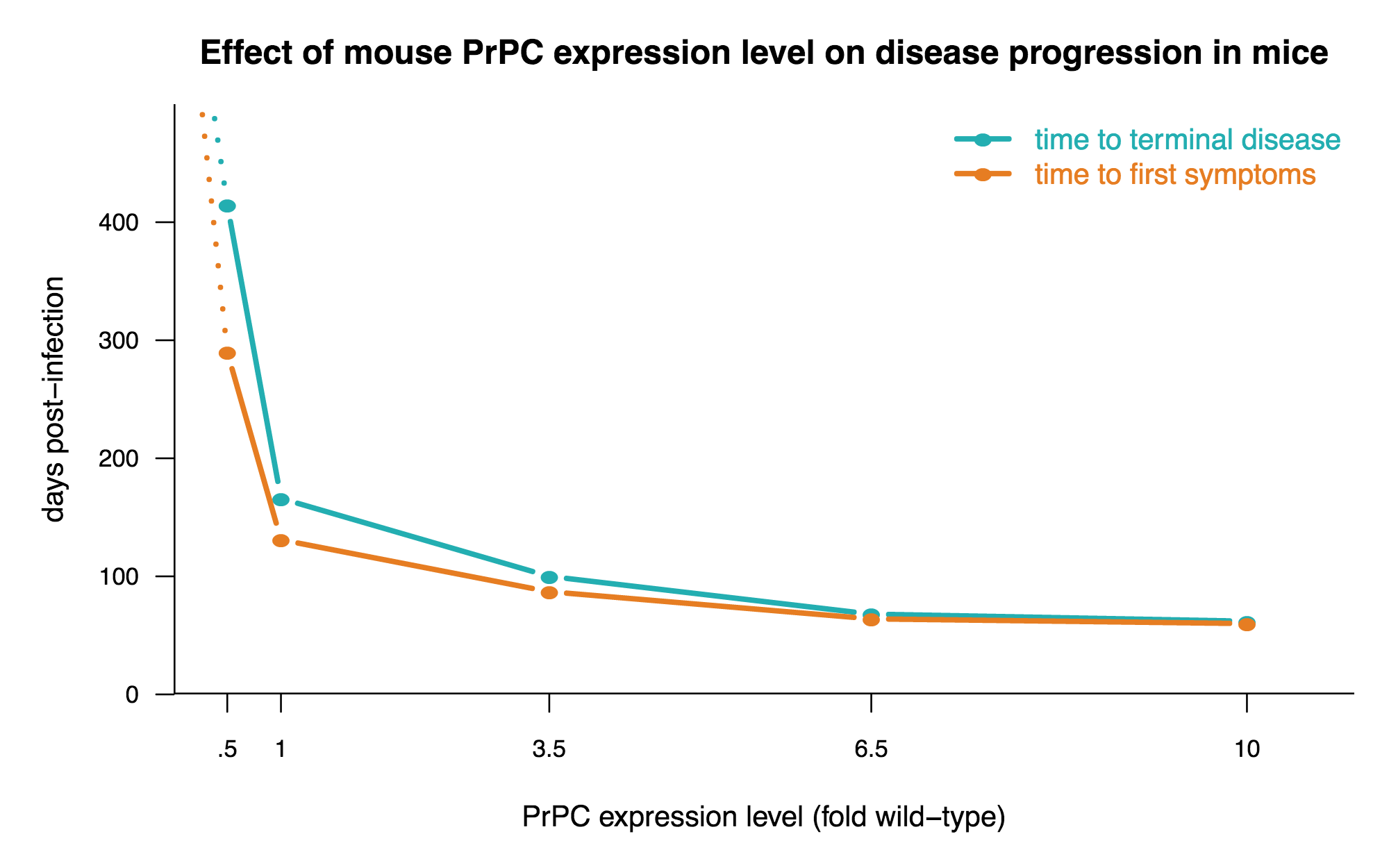

- Overexpression of PrP in mice hastens prion disease, and heterozygous knockout slows it down [Fischer 1996].

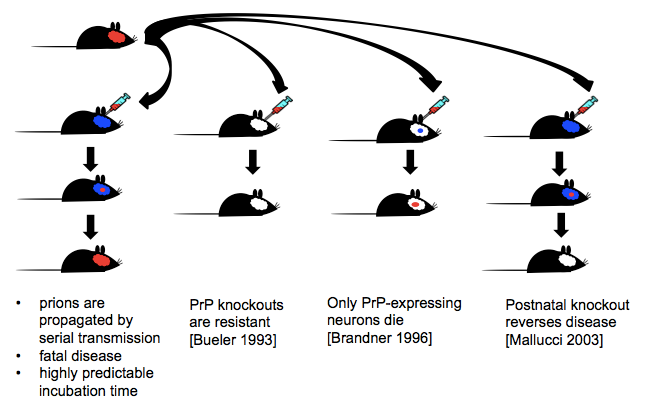

- If PrP knockout mice with a graft of PrP-expressing tissue in their brains are infected with prions, the graft will generate prions and its neurons will die, but adjacent PrP-null neurons will not. Thus, PrP is required not only for prion replication, but also for prion neurotoxicity [Brandner 1996].

- Post-natal knockout of PrP (using a Cre system) in neurons after mice are infected halts prion disease [Mallucci 2003].

- Post-natal supression of PrP expression (using a Tet-off system) after mice are infected dramatically slows prion disease [Safar 2005].

- Monoclonal antibodies to PrPC can cure peripheral prion infections in mice. Although they don’t work at all once the infection is in the brain, this still at least provides proof of principle for directly targeting PrP with a therapeutic [White 2003].

One key take-home message from the above work is that the less PrP, the better, and the more PrP, the worse. Here’s a plot of the data from [Fischer 1996] to drive that home:

In presentations I sometimes also show this handy diagram of a few key lessons from prion mouse models:

As soon as I get to talking about reducing PrP expression as a therapeutic strategy, the question arises, well, what is the knockout phenotype? Here are a few key papers on that:

- The first-ever characterization of PrP knockout mice: they’re viable, fertile, and after a large battery of behavioral tests, researchers couldn’t find a single thing wrong with them [Bueler 1992].

- In the years after Bueler 1992, scads of PrP knockout mouse phenotypes were reported, but most or all of them are pretty dubious (this is a review) [Steele 2007]. Most importantly, note the “Caveats of a Phenotype” section of this paper and don’t believe everything you hear.

- 18 years after the first PrP knockout mouse, we finally get to an undeniably real phenotype of PrP knockout mice: a defect in peripheral myelin maintenance [Bremer 2010]. As you read, notice the sheer number of experiments required to show that this phenotype is actually real: four different knockout lines, bred to multiple different mouse strain backgrounds, rescued (or not rescued) with several different transgenes. None of the other knockout phenotypes reported to date have come close to this level of evidence.

My ultimate reason for interest in knockout phenotypes, of course, is to know whether reducing PrP levels would be safe. I think the clear answer is yes. The myelin defect reported here begins early in life and appears histopathologically severe, but in terms of consequences, it’s still pretty mild: at 60 weeks of age, the difference in hot plate response among the mice is tiny, to the point of not even being detectable in some mouse strains. And the defects are not seen at all in heterozygous knockout mice. So in the face of how terrible prion disease is, nothing here reduces my enthusiasm for reducing PrP expression as a therapeutic strategy. (We now have some, albeit very limited, evidence that heterozygous knockout is tolerated in humans too [Minikel 2016]).

While the proof of concept for therapeutic targeting of PrP is very strong, the small molecules that have proven most effective at delaying prion disease in mice don’t reduce PrP levels, and most, in fact, don’t seem to interact directly with PrP at all. They were discovered in phenotypic screens, and their mechanisms of action are still unknown. When I describe the current state of the field I usually say something like this:

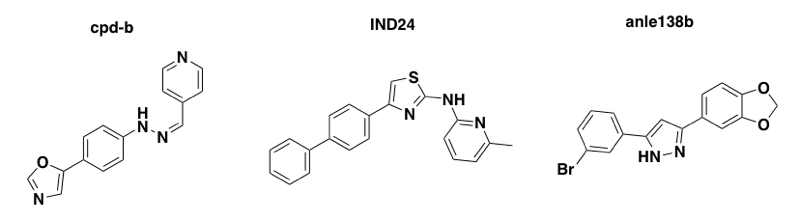

Phenotypic screening in prion-infected mouse cells has yielded small molecules that reduce prion replication in cell culture and extend life in prion-infected mice by 2-4X. This success demonstrates, in principle, the feasibilty of small molecule therapy for prion disease. None of these molecules, however, has shown efficacy in humanized mice infected with human prions.

Above: three molecules discovered in phenotypic screens, with unknown mechanisms of action, that extend survival in mice infected with mouse prions but are useless in humanized mice infected with human prions.

That’s the current state of the field. To learn more about that current state and how we got here, I offer you just a tiny fraction of the many excellent papers out there about prion therapeutics:

- The first phenotypic screen of any appreciable scale in prion-infected cells [Kocisko 2003]. They screened ~2,000 bioactives, and none of the hits proved effective in vivo, but this nonetheless formed a template for much of what came after.

- Demonstration of in vivo efficacy of pentosan polysulfate (PPS) [Doh-Ura 2004]. PPS is not a small molecule — it’s a huge molecule. Until the first effective small molecules came along a few years later, this was the best preclinical success out there. One recurring theme, of which this is an early example, is that the earlier you treat, the more efficacy you get, and if you treat after onset of symptoms, you get zero efficacy.

- The identification of cpd-b, the first small molecule effective against prion infections in the brain [Kawasaki 2007]. This provided the first hint that small molecules can have differential effects against different prion strains.

- The first report of prions evolving drug resistance, in this case to quinacrine [Ghaemmaghami & Ahn 2009]. This is a phenomenon which has since been observed for many other compounds.

- The story of 2-aminothiazole antiprion compounds, which pretty much shows the current state of the field: people have found small molecules that are orally bioavailable and remarkably effective against prion infections in the brain, but they only work against some strains of prions, and even then, their efficacy can in some cases be limited by the evolution of drug-resistant strains [Berry 2013].

- A very thorough battery of experiments documenting what we know about the 2-aminothiazole antiprion compounds, particularly how their efficacy changes as a function of disease timepoint, dosing regimen, and PrP expression level [Giles 2015]. While there is still no efficacy against human prion strains, the demonstration of a 4X increase in survival time for prophylactic treatment should convince you, if nothing above did, that therapy for prion disease is possible.

To summarize all of the above considerations, I often include a table something like the following. It includes a few more references not mentioned above, but you don’t necessarily need to read all of them to get the gist — they mostly just validate and shore up conclusions mentioned above.

| therapeutic strategy | proofs of concept |

|---|---|

| Reduce PrPC levels | PrP knockout mice are resistant to prion disease [Bueler 1993] PrP expression level and incubation time are inversely correlated [Fischer 1996] Disruption of PrP expression using Cre or Tet-off systems can delay or reverse disease [Mallucci 2003, Safar 2005] PrP knockout is tolerated in mice, cows, and goats, and there exist healthy older humans heterozygous for PRNP loss-of-function variants [Bueler 1992, Manson 1994, Richt 2007, Yu 2009, Benestad 2012, Minikel 2016] |

| Stabilize PrPC conformation | Partial denaturation of PrPC, for instance with guanidine, facilitates in vitro conversion to PrPSc [Kocisko 1994] “Stapling” of PrPC with certain non-native disulfide bonds prevents conversion to PrPSc[Hafner-Bratkovic 2011] Monoclonal antibodies against PrPC cure prion-infected cells and peripheral prion infections [Peretz 2001, White 2003] |

| Antagonize PrPC to PrPSc conversion | Certain heterozygous missense variants in humans, and PrP transgenes from different species in mice, act as dominant negatives, inhibiting PrPSc formation [Palmer 1991, Telling 1995] Small molecules discovered in phenotypic screens, which reduce PK-resistant PrPSc formation in cell culture, extend life in mice infected with prions [Kawasaki 2007, Berry 2013, Wagner 2013] |

In thinking about therapeutics, it will also help you to know some basics about PrP. Let me help with one that non-prion people constantly forget: PrP is a GPI-anchored protein that can be found transiting through the secretory pathway, living on the outside surface of the cell, or in the endosomal/lysosomal pathway. Here is a handy diagram to help you remember some things about PrP’s localization and life cycle:

Above I’ve only depicted PrPC and have not depicted where in the cell PrPSc replication occurs. That’s in part because there isn’t total agreement or clarify on this point, though as I reviewed in this MoA post it seems like PrPSc replication probably occurs somewhere in the endosomal/lysosomal pathway at right.

Here are just a few classics on prion cell biology:

- In prion-infected cultured cells, PrPC appears to transit to the cell surface before being re-internalized and then converting to PrPSc in some internal compartment; PrPSc is degraded in these cells, but it has a longer half-life than PrPC. [Caughey 1990, Borchelt 1990, Caughey & Raymond 1991].

- PrPSc undergoes N-terminal truncation by lysosomal proteases, implying it reaches the lysosome at some point in its life cycle [Caughey 1991].

- Characterization of alpha cleavage, shedding, and endocytic recycling of PrPC [Harris 1993, Shyng 1993].

And you might also want to know a bit about two oft-mentioned tools of the prion trade:

- Protein misfolding cyclic amplification (PMCA) is a process of cyclic sonication and incubation that allows cell-free amplifcation, or generation, of PK-resistant PrPSc and prion infectivity [Saborio 2001, Castilla 2005].

- Real-time quaking-induced conversion (RT-QuIC) is a process of cyclic shaking and incubation that detects prions with remarkable sensitivity, while not generating any new infectivity [Wilham 2010, Atarashi 2011].

Again, there’s a whole world of other amazing scientific literature out there on prions that I haven’t even touched on here. If you had to pick a rare disease to have, prion disease really is amazingly well-studied and a lot is known. But for an “introductory” reading list like what I was asked for, this post is already way too long.