Curcumin as prion therapeutic

Read with caution! This post was written during early stages of trying to understand a complex scientific problem, and we didn't get everything right. The original author no longer endorses the content of this post. It is being left online for historical reasons, but read at your own risk. |

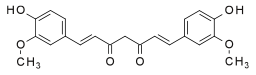

Curcumin (above) is a phenol compound found in turmeric (top), responsible for its characteristic yellow color. For at least a couple of decades now there has been interest in curcumin’s possible neuroprotective and anticancer effects, in part due to observations of apparently lower rates of Alzheimer’s and colon cancer in South Asia compared to the U.S. These effects are purported to be due to at least two roles: as a free radical scavenger and as an anti-inflammatory.

The first study to examine curcumin as a prion therapeutic was Caughey 2003. In addition to the antioxidant properties and low toxicity of curcumin, Caughey noted that the molecule has some structural similarities to Congo red, which is known to inhibit PrP plaque formation, but that unlike Congo red, curcumin has no charged groups, so it’s more likely to cross the blood-brain barrier.

Caughey’s experiments in scapie-infected neuroblastoma (ScNB) cell culture showed that curcumin substantially inhibited of PrP-res formation even at reasonably low concentrations such as 10 nM. So Caughey tested dietary curcumin in hamsters infected intracerebrally with 10-2 dilution of 263K scrapie brain homogenate. Different groups of hamsters received curcumin treatment in their diet beginning 14 days before infection, 0 days post infection (dpi) or 40 dpi. All of the treatment groups lived very slightly longer than the control, but none of the differences were statistically significant. The dietary concentration of curcumin was 0.2% wt/wt. Caughey also tried a high-dose group with 2% wt/wt curcumin in food, also with no significant delay in disease onset.

| treatment started dpi | dose | days to onset | control onset | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -14 | 0.2% wt/wt | 85.3 ± 4.0 | 82.6 ± 3.9 | ns |

| -0 | 0.2% wt/wt | 84.1 ± 4.3 | 82.6 ± 3.9 | ns |

| 40 | 0.2% wt/wt | 83.5 ± 4.1 | 82.6 ± 3.9 | ns |

| 45 | 2% wt/wt | 85.4 ± 4.7 | 82.6 ± 3.9 | ns |

So: no effect in vivo in this study. In concluding, Caughey speculates about a pharmacokinetic reason for this, and offers that curcumin is still a worth lead compound for further drug development.

People didn’t give up on curcumin after Caughey’s negative result in hamsters. Hafner-Bratkovic 2008 provided a large battery of biochemical evidence for the idea that curcumin interacts directly with PrP. If true, this provides another mechanism of action beyond any anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of curcumin. Riemer 2008 tested curcumin in scrapie mice, the only other animal trial of curcumin that we’re aware of.

Riemer’s mice were intracerebrally infected with 10-3 or 10-4 dilutions of 139A brain homogenate and drug treatment was commenced at 100 dpi. Here are results for curcumin:

| infectious titer | curcumin dose | treatment survival | control survival | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-3 | 500 mg/kg/day | 174±9.0 | 174±8.6 | ns |

| 10-4 | 50 mg/kg/day | 208±8.4 | 192±9.2 | <.01 |

| 10-4 | 500 mg/kg/day | 192±9.7 | 192±9.2 | ns |

So here’s an interesting result. The lower dose of curcumin was significantly effective (8% delay in disease onset) but the higher dose wasn’t. Riemer speculates as to the possible reason:

Inhibition of multiple kinases and other drug effects at high curcumin concentrations may provide an explanation for this observation, as this spectrum of activities could potentially offset beneficial drug effects (Gautam et al., 2007; Menon & Sudheer, 2007).

Hmm, so more isn’t always better. Where did all these doses come from in the first place? Who said 50 mg/kg and 500 mg/kg were the right doses to test? Riemer states that doses in this study were following Lim 2001, one of the first studies of curcumin in Alzheimer’s mouse models. Lim’s results are important and are also cited by Caughey. Lim used APPSw mice– transgenic mice carrying the so-called Swedish double mutation in the human APP gene, one of the hereditary causes of Alzheimer’s. The study didn’t actually measure cognitive, behavioral or lifespan endpoints in the mice; instead, it consisted of immunohistochemistry to see how curcumin treatment had affected various pathways believed to be important in Alzheimer’s pathogenesis. The study used two doses of curcumin: 160 ppm and 5000 ppm in food. So these work out to .016% and .5% of the food. Here were the results compared to control mice that did not eat curcumin (only significant results are shown, otherwise ns for not significant):

| measure | low dose | high dose |

|---|---|---|

| IL-1β | -61.8% | -57% |

| GFAP (marker of astrocytic gliosis) | -16.5% | ns |

| Oxidized proteins | -61.5% | -46.3% |

| SDS-insoluble Aβ | -39.2% | ns |

Notice that while both doses had some significant effects, the low dose performed categorically better than the high dose.

In light of Lim’s result, it’s not so surprising that Riemer also had better luck with lower doses. The doses in the two studies are supposed to be comparable: Riemer states that doses were “adjusted to previously described ranges”, citing Lim for curcumin. But Lim’s doses are given in ppm of food provided ad libitum. This primer from Purdue says that “An adult mouse will eat approximately 15 grams and drink 15 ml of water per 100 grams of body weight per day”, so that’s 150,000 mg/kg/day of food. So 160ppm curcumin works out to 150,000*160/1,000,000 = 24 mg/kg/day, and 5000 ppm works out to 750 mg/kg/day. Caughey used 0.2% and 2.0% wt/wt in feed, which means 2,000 and 20,000 ppm respectively, but in hamsters, which eat 8-12 grams of food per 100g body weight per day according to Purdue. So assuming 10g as a midpoint, Caughey’s doses of curcumin work out to 200mg/kg/day and 2,000 mg/kg/day. That’s in hamsters, so you need to use body surface area to convert between species. For comparability, here are the doses from all three studies expressed as equivalent doses for a 70 kg person:

| study | low dose | high dose |

|---|---|---|

| Lim 2001 | 136 mg | 4256 mg |

| Caughey 2003 | 1891 mg | 18919 mg |

| Riemer 2008 | 283 mg | 2838 mg |

Wow. So Caughey’s low dose is actually closer to Lim’s and Riemer’s high dose, and Caughey’s high dose is enormous. I did a bit more digging to put these figures in perspective with the human diet. Some of the hype about curcumin seems to have originated from observations that South Asians have apparently lower rates of dementia than Americans do (Lim cites Ganguli 2000, Muthane 1998). There are a million confounding factors, and in fact the studies don’t even compare Indians in India to Indians in the States; they compare Indians in India to white people in the States. For obvious reasons no one has convincingly established that curcumin is part of the reason, but if you do buy that curcumin has something to do with it, then the amount of curcumin in the human diet might be a good starting point for a relevant dose.

I dug up a study quantifying the curcumin content of different brands of turmeric (and curry powder) sold in Asian grocery stores in the U.S., putting the curcumin content of turmeric at 0.58% to 3.14%, with an average of 1.51% [Tayyem 2006 (ft)]. And according to this calculator, turmeric has a density of about 7g/Tbsp. 7g*1.51% = 106 mg of curcumin per tablespoon of turmeric. I asked a couple of Indian-born-and-raised friends how much turmeric they eat, and got answers of a half teaspoon and two teaspoons per day. One tablespoon (= three teaspoons) is probably on the upper end of what anyone actually eats, and that would be average ~106 mg of curcumin. So the human diet is probably a bit lower than Lim’s low dose, less likely to approach Riemer’s low dose, and will never be anywhere near the high doses– Caughey’s high dose is like 11 cups of turmeric per day.

Obviously, Caughey was not proposing that anyone eat 11 cups of turmeric. It is perfectly reasonable to get much higher doses of a drug in supplement form than from the diet, and given the low toxicity of curcumin, it was an excellent idea to ask whether really high doses of curcumin might be especially effective against prion disease. But now with the benefit of hindsight, the fact that lower doses were more effective in both Lim’s and Riemer’s studies makes it seem as though perhaps curcumin could have been effective in Caughey’s mice at a lower dose. Another observation is that Caughey’s hamsters were infected with a high dose of scrapie: 10-2 dilution, compare at 10-3 or 10-4 in Riemer and most of the other therapeutic studies reviewed elsewhere on this blog. So perhaps curcumin could be effective against a lower infectious titer or in a genetic model where infectious material accumulates gradually over the animal’s lifetime.

In all three of these studies, curcumin was administered orally, so the astute reader will ask, does curcumin even get to the brain from the diet? Sharma 2007 fed human volunteers 3.6g/day of curcumin and and found levels of curcumin in the GI tract that were potentially therapeutically relevant for colorectal cancer, but noted that “There appears to be negligible distribution of the parent drug to hepatic tissue or other tissues beyond the gastrointestinal tract.” That’s referring to free curcumin (either as the diketo shown in the molecular diagram at top, or either of two equivalent enol forms); the authors do note that curcumin gets glucuronidated or sulfated in the gut. Vareed 2008 found that there are appreciable levels of glucuronide and sulfate forms of curcumin in the serum after oral administration. A number of different approaches such as chemical modification and encapsulation in nanoparticles have been attempted to improve the bioavailability of curcumin — for a reveiw, see Anand 2007.

The most fascinating part of the curcumin bioavailability question is the interaction with piperine, the alkaloid compound that makes black pepper peppery. Shoba 1998 found that when humans eat piperine (evidently a known inhibitor of glucuronidation) at the same time as curcumin, the bioavailability of the curcumin increases 20-fold. This is apparently a pretty serious proposition, as a 2005 U.S. clinical trial led by Michael Seiden (then in charge of clinical cancer research at MGH, now CEO of the Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia) on the bioavailability of curcumin was supposed to look at curcumin/piperine interactions. As far as I can tell online, results from that study were never published.

Anyway, as far as I can tell no one has actually addressed the question of whether curcumin needs to be in its free and original form in order to have neuroprotective effects. The mice and hamsters in these Alzheimer’s and scrapie studies were presumably not fed black pepper, and yet Lim’s results show pretty convincingly that something was different in the brains of APPSw mice treated with curcumin: lower IL-1β, less Aβ buildup, less astrocytic gliosis. Whether or not any of this actually points to a therapeutic effect against Alzheimer’s pathology, much less an effect that would translate to humans, would require further study; but Lim’s results are highly significant that oral administration of curcumin brings about biochemical changes in the mouse brain. So there is some disconnect between this finding and the pharmacokinetic evidence that free curcumin doesn’t make it very far past the intenstines. Perhaps curcumin glucuronide or curcumin sulfate make it to the brain and have therapeutic effects, or perhaps these compounds in the serum lead to downstream therapeutic effects in the brain.

tl;dr: There are a lot of open questions about how curcumin might exhibit neuroprotection and at what dose, but evidence suggests it works better at a lower dose on the order of 50mg/kg/day in mice and that it might be worth further testing against prion diseases.