Cell Biology 08: Cell Cycle Regulation and Checkpoints

These are notes from lecture 8 of Harvard Extension’s Cell Biology course.

Lecture 7 introduced the cell cycle and the role of microtubules therein. This lecture will discuss the regulatory mechanisms and biochemical checkpoints throughout the cell cycle. Disclaimer: these notes are not my finest work – a lot of this is just a collection of random facts.

cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs)

CDKs are important master regulators of the cell cycle. Their role is to phosphorylate proteins on either S or T amino acids and thereby regulate the activity of those proteins. Yeast have just one CDK (Cdk1), while ‘metazoans’ (animals) like us have nine, of which four are really critical to the cell cycle and will be introduced today.

How are the CDKs themselves regulated? The levels of these proteins remain pretty constant throughout the cell cycle, yet their levels of activity rise and fall cyclically. CDKs need to hydrolize ATP for energy in order to perform phosphorylation. They have an ATP binding cleft whose ability to bind ATP is regulated by two mechanisms. First, CDKs have a ‘flexible T loop’ which contains a threonine (T) residue which normally blocks the ATP binding cleft, but not when the T is phosphorylated. Second, cyclins bind CDKs and induce a conformational change that also helps to expose the ATP binding cleft. Therefore a fully active CDK is one which is both phosphorylated at the T on the T loop and is bound to a cyclin.

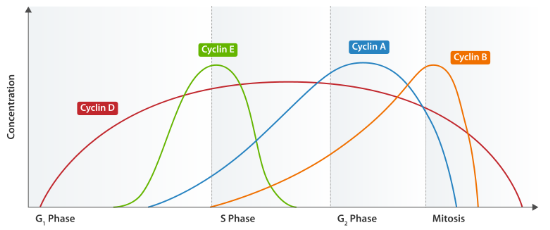

The various activities of the cell cycle, then, are determined by the combination of cyclins and CDKs that are active at each stage, as shown in the following table:

| cell cycle stage | cyclins | CDKs | comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | Cyclin D | CDK4&6 | Can react to outside signals such as growth factors or mitogens. |

| G1/S | Cyclins E & A | CDK2 | Regulate centrosome duplication; important for reaching START |

| S | Cyclins E & A | CDK2 | Targets are helicases and polymerases |

| M | Cyclins A & B | CDK1 | Regulate G2/M checkpoint. The cyclins are synthesized during S but not active until synthesis is complete. Phosphorylate lots of downstream targets. |

All cyclins contain a conserved 100 amino acid ‘cyclin box.’ Cyclin/CDK complexes regulate the cell cycle both by promoting activites for their respective stages, and by inhibiting activites for future cell cycle stages that must not yet be reached. Therefore cyclins must be able to be both generated and degraded in order for the cell cycle to proceed.

Antibodies against Cyclin D inhibit entry into the S phase, which can be measured by whether BrdU (a fluorescent nucleotide analog) gets incorporated into DNA (which only happens during synthesis).

DNA replication starts at ‘prereplication complexes’ that get assembled at origins of replication during early G1 phase. The S-phase cyclin/CDK complexes phosphorylate these complexes and thereby trigger replication starting from these ‘origins’.

Here is a bit more about how the CDKs are regulated through phosphorylation. A CDK-activating kinase (CAK; a trimeric complex composed of CDK-7, Cyclin H and Mat1) phosphorylates amino acid T160 in CDK, located at the T loop, thereby activating CDK. CDKs are also regulated by CDK inhibitors p27 (CDKN1B gene), p21 (CDKN1A gene) and p57 (CDKN1C gene), which bind to and inhibit both of the G1 CDKs (CDK4 & CDK6). p27 does this by physically blocking the cyclin/CDK complex’s interaction with its targets. p15 (CDKN2B gene) and p16 (CDKN2A gene) are both Ink4s (“inhibitors of kinase 4″, though they also inhibit CDK6) control the mid G1 phase by binding to CDK4 and CDK6 and blocking their binding to cyclin D. This results in decreased phosphorylation of target proteins. Overexpression of p16 arrests the cell cycle by inhibiting CDK4/Cyclin D during early G1.

Another inhibitor called Rb prevents entry into the S phase by binding to E2F transcription factors. E2Fs are transcriptional activators when they act alone but repressors when bound to Rb. The mid-G1 cyclin/CDK complexes partially phosphorylate Rb, reducing its binding to E2Fs; the late G1 complex of CDK2/Cyclin E completely phsophorylates it, preventing its binding to E2F. E2Fs can then act as transcriptional activators for genes needed in the S phase.

S-phase cyclin/CDK complexes accumulate in late G1, but are still bound to an inhibitor called Sic1. But G1 CDK/cyclin complexes polyphosphorylate Sic1 at six sites. When and only when all six sites are phosphorylated (which takes a while), Sic1 is released, whereupon it gets polyubiquitinated and therefore degraded by the proteasome. The S-phase cyclin/CDK complexes are then free to induce DNA replication. This mechanism allows the cell to accumulate many of these complexes ‘ahead of time’ (starting in G1) but then post-translationally activate them all at once in order to suddenly start massive-scale DNA replication in the S phase.

Targeting of proteins such as Sic1 to the proteasome is mediated by two complexes SCF (Skp, Cullin & F-Box) and APC/C (anaphase promoting complex / cyclosome), each composed of ubiquitin and a protein ligase. These two control three major transiations in the cell cycle:

- the onset of S phase by degradation of Sic1

- beginning of anaphase by degradation of securin

- exit from mitosis by degradation of Cyclin B.

APC/C is composed of several proteins including but not limited to cullin (APC2), Ring (APC11) and SCF-like protein. APC/C’s role is to ubiquitinate (add ubiquitin tags to) proteins, thus flagging them for degradation by the proteasome. Cdc20 casues APC/C to polyubiquitinate the anaphase inhibitor securin in point (2) above. Cdh1 causes APC/C to polyubiquitinate Cyclin B in point (3) above. Cdh1 is itself regulated by phosphorylation – the G1/S cyclin/CDK complexes phosphorylate it, preventing it from acting too soon; Cdc14 then later activates Cdh1.

SCF has no binding partner – rather, its ability to ubiquitinate targets (substrates) is determined by the latter’s phosphorylation state. SCF is active throughout the cell cycle; the cell regulates its activity by regulating the phosphorylation of SCF’s targets. An example is Sic1 (above).

MPF (Maturation or Mitosis Promoting Factor depending on who you ask) is a fancy word for the cyclin B / CDK1 complex, which is active in the M phase – actually, required in order for entry to the M phase. Here’s how MPF itself is regulated. CDK1 has two phosphorylation sites (in vertebrates; only one in yeast) at amino acids Y15 and T161. In animals, phosphorylation of Y15 is inhibitory, while phosphorylation of T161 is activating. The cyclin/CDK2 complex begins its life wholly unphosphorylated (thus inactive), then Wee1 phosphorylates Y15, CAK then phosphorylates T161 too, then finally Cdc25 removes the Y15 phosphorylation, allowing the complex to be active (about 100x more activity than with neither site phosphorylated). Cdc25 overexpression results in premature removal of this Y15 phosphorylation so that the cell enters the M phase before it has had enough time to grow during the G2 phase. This results in ‘wee cells’ which are literally small because the cell growth was inhibited, so that the daughter cells after mitosis are smaller than the mother cell was. (Hence the name Wee1, which is of course backwards since Wee1 acts against the ‘wee cell’ phenotype).

Once a cell passes the restriction point (R) in late G1, it is committed to passing through the S phase.

Many cancers involve a loss of p16 leading to cyclin D1 overexpression. Other cancers (esp. late onset cancers – breast, lung, bladder) often have hyperphosphorylation of Rb leading to release of E2F to promote the cell cycle. This hyperphosphorylation can be caused by loss or ‘misexpression’ of one or more things (p16,…?)

regulatory steps in the cell cycle

Here is an overview of what are considered to be the 9 fundamental steps of cell cycle regulation. Cell starts in phase G0 or G1.

- DNA replication machinery begins to assemble at origins of replication

- G1 cyclin-CDK complexes inactivate Cdh1

- G1 cyclin-CDK complexes activate the S-phase cyclin-CDK expression

- G1 cyclin-CDK complexes phosphorylate and thereby inactivate S-phase inhibitor(s?)

- SCF polyubiquitinates the phosphorylated S-phase inhibitor, targeting it for proteasome degradation. Cell enters S phase.

- S-phase cyclin/CDK activates the preplication complexes that began to assemble in step 1. S phase and G2 phase happen.

- Cdc25 phosphatase activates M-phase cyclin/CDKs. Cell enters M phase and gets to metaphase.

- APC/C and Cdc20 target securin for proteasomal degradation. Cell advances from metaphase to anaphase.

- CdcA phosphatase activates Cdh1, making it possible for APC/C and Cdh1 to target the M-phase cyclins for proteasomal degradation. Cell returns from M phase to G0 or G1 phase.

Step 7 relies on a mechanism to recognize unreplicated DNA and stalled replication forks in order to ensure that mitosis does not proceed before all DNA has been replicated. Two proteins are involved in this mechanism: ATR and Chk1 (pronounced ‘check one’). Both are protein kinases that ‘sense’ the state of DNA. ATR is located at the replication fork and activates other protein kinases, leading to phosphorylation and therefore activation of Chk1 which is also a kinase. Chk1 then phosphorylates and inactivates Cdc25, which would otherwise activate MPF. ATR thus continues to prevent M phase entry until replication is complete (= when replication forks are gone?).

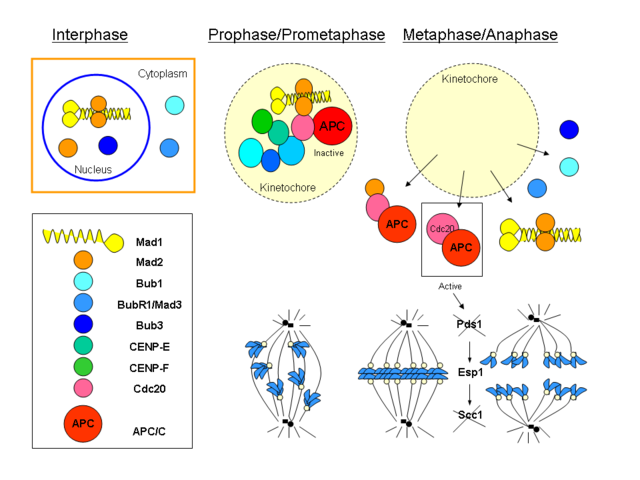

Step 8 involves an even more complicated mechanism called the mitotic spindle assembly checkpoint which prevents entry into anaphase until each and every kinetochore is attached to a microtubule. Sister chromatids are held together at the centromeres by a multi-protein complex called cohesin (composed of smc1, smc3 and kleisin). Separase is an enzyme that cleaves part of cohesin kleisin, physically releasing the chromatids. Securin inhibits separase to prevent separation of the chromatids. Once all kinetochores are attached, securin is targeted for degradation, thus freeing separase from inhibition and causing entry into anaphase. The mechanism for ‘knowing’ when to target securin for degradation is the really complicated part. It involves Mad1, Mad2, Cdc20, APC/C. Mad2 can have an ‘open’ or ‘closed’ conformation. ’closed’ Mad2 inactivates Cdc20, thus preventing its association with APC/C. This pretty Wikimedia commons graphic by Dawn08 gives some sense of how complicated it all is:

Proper segregation of the daughter chromosomes is monitored by the ‘mitotic exit network’. At this stage, MPF is inactviated, Cdh1 is dephosphorylated, and the cell can enter telophase.

There is also a ‘spindle position checkpoint’. In yeast, Tem1 becomes associated with the spindle pole body at the centrosome.

‘DNA damage checkpoints’ detect whether DNA has been damaged (e.g. by UV light, chemicals, etc.). The cell cycle arrests in G1 or S, preventing the copying of damaged bases until they can be repaired. Arrest in G2 allows double-stranded breaks to be repaired before mitosis. Tumor suppressor genes are important in preventing replication of damaged DNA. Cells can sense UV or gamma radiation damage through a protein called ATM/R. ATM/R phosphorylates and activates Chk2, which then phosphorylates Cdc25, marking it for degradation. ATM/R also stabilizes the tumor suppressor p53 (gene: TP53), which is a transcription factor that activates p21, which (inhibits the G1 CDKs? and) arrests the cell cycle in G1. p53 undergoes loss-of-function mutations in perhaps 50% of cancers, and many of the mutations are dominant negative so only one allele need be mutated. Mdm2 also regulates p53, and ATM/R prevents Mdm2′s binding to p53. p53 is regulated by multiple means, and also has multiple roles in promoting DNA repair, cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis.