Git tutorial

This post is my presentation for a half-hour tutorial on git and GitHub delivered to my department, the Analytical and Translational Genetics Unit at MGH, on August 27, 2014 as part of our summer tutorial series. An important disclaimer: I myself am far from being a git expert! I volunteered to give this tutorial because I figured it would be a chance to shore up my own basics. If you see any mistakes, please leave a comment below.

Why use version control?

Like me, the following statements probably describe many of you:

- I only write one-off scripts to be used for a single project.

- I’m the only one who works on them.

- Git sounds complicated and I don’t want to be distracted from my science.

So you may wonder, “why would I use version control?” Well, here are some reasons:

- Creates a backup of everything you do.

- Delete old stuff without worrying if you’ll need it again - no “mycode_old.py”, and no commented-out old lines.

- Revert to an earlier version whenever you want. This lets you try out a change without risking not being able to get your code to work again.

- Collaborate easily without emailing attachments.

And that’s just the simple stuff - once you get fluent in git you’ll find there is so much more you can do with it.

So what are git and GitHub?

git is a version control system. Instead of storing a whole copy of ever version of every file, it just stores the differences between each version. GitHub is a hosting site and social network built around git. There are other version control systems (subversion and mercurial), and other social networks that can run git (BitBucket). Here are a few good reasons to use git and GitHub in particular:

- They’re the official system at ATGU and your colleagues are using it.

- The user community comprises many of the world’s best coders. This is probably why the git system is complicated and arcane, but also why it’s highly reliable and full-featured.

- Almost any question you could have has already been answered on StackOverflow

- GitHub is an awesome social network with nice collaboration features.

How does it work?

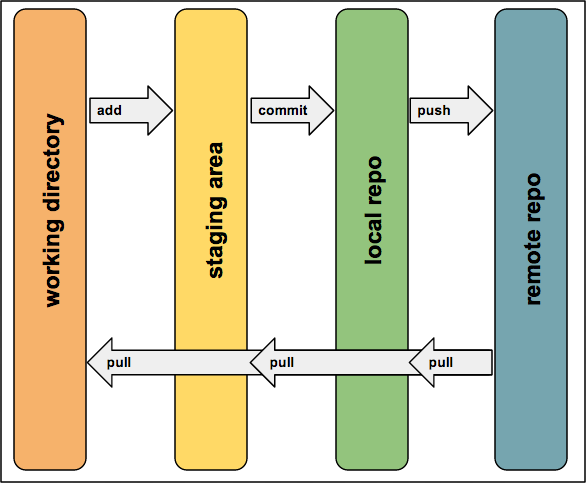

Here is a diagram of the different zones of your git universe and how different actions affect them.

If your needs are relatively simple, then in a typical usage you would:

- Create local files however you like - maybe in your favorite text editor

git addyour changes to be tracked by gitgit commityour changes to your local gitgit pushyour changes from local to GitHub.comgit pullany remote changes to your local

We’ll go through examples of all this today.

Time for an example

Here’s an example we’ll walk through in the tutorial. To follow along and do this yourself, you’ll want to go to GitHub.com and register yourself an account. You can have unlimited free public repositories; their business model is based on charging for private repositories. If you have a .edu email address, though, you can sign up for an education discount which gives you five free private repos. You’ll also need to install and configure git.

First, we’ll create a directory for our project, and initialize a local git repository with git init:

mkdir fibonacci # create a folder for our project

cd fibonacci

git init . # start a git repo locally

Now we have a local git repo, though we still haven’t connected to anything on the web. Let’s add some Python code to calculate the nth Fibonacci number:

def nth_fibonacci(n):

n = int(n)

fibs = [1,1] # initialize with first two elements

while len(fibs) < n:

fibs.append(fibs[-2]+fibs[-1])

return fibs[n-1]

And now let’s add that code to our staging area and commit it to our local repository.

git add nth_fibonacci.py # add the new python code to be tracked by git

git commit -m "calculate nth fibonacci number" # commit the changes to the local repo

Now that we have some work, we’ve got something to lose! Let’s not just keep everything locally - let’s go to github.com and start a new public repo which will hold our work for all the world to see.

For this example, we won’t initialize the repository with a README. If you do that, then you have some work that’s only local (your Fibonacci code) and some work that’s only remote (your README) and you’ll have to reconcile the two versions of the repository. We’ll get to that in a minute, but I want to cover some more basics first.

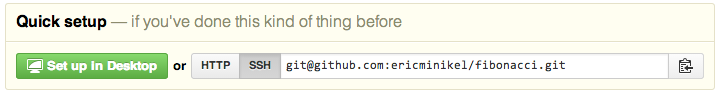

Once your repository is created, you’ll get an ssh link you can use to connect your existing local repository to it.

GitHub will also give you instructions for how to do this connecting. We’ll only use these two lines:

git remote add origin git@github.com:ericminikel/fibonacci.git # the github remote is now named "origin"

git push -u origin master # set the "origin" remote to be upstream of the local "master" branch

The first line tells git (which is a program running locally on your machine) to consider ericminikel’s fibonacci repo on GitHub.com as a remote copy of your local repository. You’ll refer to this remote copy as “origin”. The second line sets a default: your local “master” copy corresponds to the remote “origin” copy. The -u stands for upstream: it means that “origin” is upstream of “master”. One needs to know a lot more about git to understand why any of this matters, but don’t worry about it for now - remember we just copied this code from what GitHub told us to do, so we’re not actually doing anything fancy or scary.

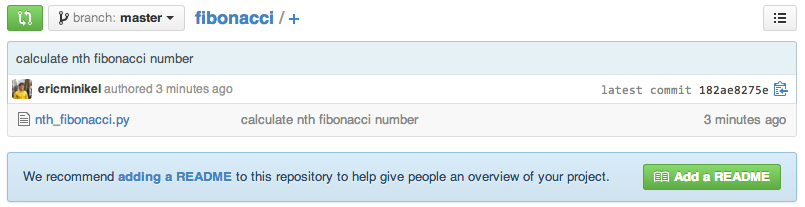

Now let’s have a look at our remote repository. Look - it’s now in sync with our local! The Fibonacci code that we created locally is there - along with a message reminding us that we really should add a README.

So let’s go ahead and add a README:

echo "This is just an example git repo for a tutorial on git." > README.md

Quiz: based on what you know about the four “zones” of your git universe above, where is this README file?

Answer: We can type git status to learn more. It turns out that it is simply in our working directory - git considers it an “untracked” file. If we git add it and then git status again, we find that now it’s being “tracked” as a “new file”:

git status # where is the README currently?

git add README.md # add to staging area

git status # now where is the README?

If we’re happy with our changes, then we can commit them to our local repo.

git commit -m "added a readme" # commit to the local repo

Quiz: now if we go back to the remote repo on GitHub.com, what will we see?

Answer: the new README is not there yet - we’ve only committed it to the local repo. If we want it to be on the web, we’ll need to push it there:

git push # push to remote repo

If we go back to GitHub, now we see our changes.

Now suppose we’re browsing the web and we stumble upon Binet’s formula, and read about how to implement it. We get excited to use that. Let’s open a text editor and change our Python code to this:

from math import floor, sqrt

def nth_fibonacci(n):

n = int(n)

phi = (1+5**.5)/2

return int(floor((phi**n)/sqrt(5)+.5))

Quiz: In what “zone” do my changes exist?

Answer: So far they are only in the working directory; git is not “tracking” them. We can find this out using git status. In fact, maybe we want to see what all has changed - to make sure the code is good - before we stage it. We can compare the old and new versions with git diff and see a line-by-line breakdown of what has changed. If we’re happy with the changes, we can roll with it:

git add nth_fibonacci.py

git commit -m "using Binet's formula"

git push

Notice that I didn’t copy my old code into a file named “nth_fibonacci_old.py”, and I didn’t leave the old method commented out in the function. I don’t need to - if I go to the file on GitHub and click on History, I can see that line-by-line comparison of the old and new versions, and if I click on “Browse code” for the old version, I see it exactly how it was before I made the change. Pretty neat!

The rest of the world can see it too. My colleague Sahar is a stickler about getting answers exactly right. She finds my code browsing on the web, and is concerned that Binet’s formula is only as exact as the floating point arithmetic in Python. She comments on the commit where I changed to the fancy method:

@ericminikel this method is only as exact as your floating-point arithmetic. In python it gives the same answer as the original method up through n = 70, but for n = 71 it gives 308061521170130 instead of 308061521170129.

Oh no! Is it true? I want to test out my code and see if Sahar is right. I realize it is kind of silly that I can’t actually run my code from the command line to see what answer it gives. To fix this problem, I create a new file “wrapper.py” in my remote repo on GitHub.com and write this code in it:

import sys

from nth_fibonacci import nth_fibonacci

print nth_fibonacci(sys.argv[1]) # call the function on the first command line arg

Quiz: Where does wrapper.py exist currently?

Answer: It is only in the remote repository, I don’t have any copy of it locally. git status doesn’t know about it either, because it only compares my working directory, staging area and local repo. If I want this work locally, I’ll need to pull it down from the cloud:

git pull

Now I have the code locally. Note that when you pull it pulls to the local repo, which in turn updates your working directory. If you have untracked files, git will leave them alone, but other than that, git owns your directory, and will write and overwrite things at will.

Now I try out my code, and sure enough, I get the answer Sahar said I would:

python wrapper.py 71

# 308061521170130

Now I want to go back to the old way of calculating Fibonacci numbers. There are a few ways of doing this - git reset, which I won’t go into today, rolls the whole repository back to how it looked at a particular commit. That’s useful in many cases, but right now I don’t want to do that because I have this new “wrapper.py” code which was added after I changed my Fibonacci code, and I don’t want to lose it. Instead, the right tool for the job is git revert. I can figure out which commit I want to revert by having a look at my log:

git log # look at the list of commits

I find the 32-byte SHA1 hash of the commit of interest, and type git revert <hash>. This creates a new commit which undoes the old commit. Note that here you’re operating in the local repo, so reverts are automatically committed. If you type git status you’ll see there are no changes - the reversion is already in the local repo. This means it also overwrites whatever I had in that file on disk - remember, git owns this directory.

If we do a little test, we’ll see that Sahar was right! The old Fibonacci code gives a different answer than above.

python wrapper.py 71

# 308061521170129

Based on this, we do want to push our changes out to the world.

That’s all for today, but we have barely scratched the surface. There are loads more cool things you can do with git.

Here is the repo we created in today’s tutorial: https://github.com/ericminikel/fibonacci.