Neurodegeneration seminar 5: 'Alpha synuclein'

These are my notes from week 5 of Harvard’s Neurobiology 305qc course “Biochemistry and Biology of Neurodegenerative Diseases”, held by Michael Wolfe and Dominic Walsh on December 1, 2014.

This week we read two reviews of Parkinson’s disease [Shulman 2011, Hirsch 2013] and three original research papers on Parkinson’s disease and alpha synuclein [Kordower 2008, Luk 2012b, Emborg 2013].

Background

Parkinsonism is the term for a collecton of symptoms including tremor, rigidity and bradykinesia (slowness of movement) which appear in people who have lost dopaminergic neurons. Parkinson’s disease refers to a specific molecular disease in which pathologically misfolded alpha synuclein (a protein encoded by the human gene SNCA) causes progressive neuronal loss, particularly concentrated in the dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra pars compacta, leading to symptoms of parkinsonism as well as, oftentimes, several other clinical signs such as postural instability, dysautonomia, constipation, depression and (late in the disease course) cognitive impairment. The motor symptoms arise from the fact that loss of neurons in the substantia nigra leads to denervation of motor neurons in the striatum. Frank motor symptoms do not appear until at least 50% of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra are lost, leading to a >70% reduction in dopamine received by the striatum, even though neurons are not lost in the striatum yet at this stage. The post-synaptic neurons that receive dopamine in the striatum do eventually die off late in the disease. Parkinson’s disease was originally characterized histologically by intracytoplasmic inclusions that stain with eosin and are usually round (“Lewy bodies”) but sometimes follow the shape of a neurite (“Lewy neurites”). These inclusions eventually proved to also be positive for alpha synuclein and ubiquitin.

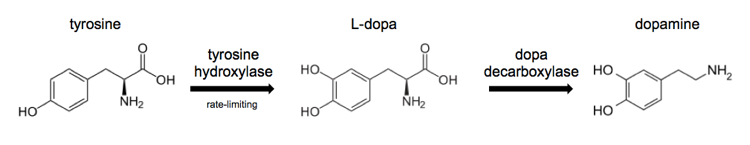

The biosynthesis of dopamine looks like this:

Current treatment options for Parkinson’s disease are based around replacing dopamine rather than addressing the underlying disease process. These approaches include:

- L-dopa to increase production of dopamine by the few remaining dopaminergic neurons which express dopa decarboxylase

- Dopamine receptor agonists

- Increasing the half-life of dopamine in the synapse

Impressively, L-dopa can reverse many early symptoms of Parkinson’s and can give people about 5 additional years of quality life compared to an untreated scenario. Yet because L-dopa relies on the remaining dopaminergic neurons, it becomes less effective as the disease course continues. It also has some toxicity and can lead to dyskinesia and psychiatric problems, thought to be mediated by changes in dopamine signaling in other regions of the brain besides the substantia nigra.

It is said that genetic forms of Parkinson’s disease are caused by autosomal dominant mutations in α-synuclein itself, or in LRRK2 or UCH-L1. Or they can be caused by autosomal recessive mutations in Parkin, PINK-1, DJ1 or ATP13A2. Patients with Parkin and PINK-1 mutations generally do not have Lewy bodies, leading some investigators to question whether these syndromes are accurately classified as being forms of Parkinson’s disease. In DJ1 patients, Lewy bodies are found in glia rather than neurons.

α-synuclein is one of the most abundant proteins in the brain. About 80% of it is found in the cytosol, and 20% is found in membrane fractions. Long thought to exist as a monomer, there is now some evidence it may exist as a tetramer. The dominant SNCA mutations A30P, E46K and A53T all appear to increase the propensity of α-synuclein to aggregate. After SNCA mutations were shown to cause to Parkinson’s [Polymeropoulos 1997, Kruger 1998] it was then discovered that the Lewy bodies, already known to be ubiquitin-positive, we are also alpha synuclein-positive - indeed, alpha synuclein is their primary component [Spillantini 1998].

Kordower 2008: Lewy body-like pathology in long-term embryonic nigral transplants in Parkinson’s disease

Starting decades ago, the transplantation of fetal brain grafts has been tested as a possible therapeutic approach to replace lost neurons in the substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease patients. Early case reports indicated a improvements in symptoms and provided some indirect evidence that the grafted neurons had survived [e.g. Sawle 1992, Piccini 1999]. Our instructor Dominic Walsh reports having met one such patient 7 years after treatment, who had undergone a remarkable remission and appeared nearly asymptomatic despite having severe Parkinson’s prior to treatment - such a recovery is unheard of in Parkinson’s, and is clear evidence that in this one patient’s case the transplantation made a real difference. Yet many patients failed to respond to transplantation at all, and a randomized trial in 34 patients at Mt. Sinai failed to see any significant benefit over 2 years of followup [Olanow 2003]. Generally only ~10% of the transplanted neurons would be dopaminergic, and some of the fetuses may have had other genetic defects that impacted neuronal function. There are a wide variety of other reasons why fetal transplantation may have failed. Some researchers believe that the positive results from these studies indicate that replacing lost neurons is a viable strategy if it can be made to work with appropriately differentiated autologous stem cells.

This study compares neuropathology in two individuals who died 4 years after receiving transplants, and one individual who died 14 years after receiving a transplant. The 14 year post-transplant individual had robust graft survival (somehow, they could tell which cells were from the graft) and the grafted cells stained positive for some markers of dopaminergic neurons, including tyrosine hyrdoxylase (TH) but not dopamine active transporater (DAT, involved in re-uptake). Although the grafted cells had survived and did not appear to be degenerating, they contained alpha synuclein aggregates. In contrast, the 4 year post-transplant individuals had cytosolic alpha synuclein but it was not aggregated. The authors concluded that “there must be either a pathogenic factor in the brain milieu that affects dopaminergic neurons or a pathological process that can spread from one cellular system to another”. That “pathogenic factor” was surely the aggregated alpha synuclein itself, as Virginia Lee and others later showed that alpha synuclein pathology is transmissible.

This paper is often cited as support for the prion hypothesis of Parkinson’s disease, and indeed, it certainly suggests that aggregates can move from cell to cell. Strictly speaking, the data only indicate cell-to-cell movement of aggregates, not recruitment of new substrate protein in grafted neurons, as they did not demonstrate that the synuclein aggregates in the graft cells were formed from graft-expressed alpha synuclein. Some observers also argue that maybe the toxic environment of the host brain caused the transplanted cells to form aggregates de novo. Interestingly, the authors themselves were pretty mild about their conclusions, but Heiko Braak wrote an accompanying commentary which endorsed this study as being strong evidence for synuclein-as-prion [Braak & Del Tredici 2008]. The same issue of Nature Medicine also featured two other brief reports about patients who had received fetal transplants [Li 2008, Mendez 2008]. One study found no pathology at all in the grafted cells in several patients [Mendez 2008] while the other study found that Lewy bodies had developed in the transplanted neurons just like Kordower found, but that the patients had a more sustained recovery from symptoms [Li 2008]. Li’s patients had less evidence of neuroinflammation surrounding the graft than Kordower’s patients, which some observers have taken as evidence that neuroinflammation and/or some non-cell-autonomous effect involving glia is involved in the neuronal impairment of Parkinson’s disease.

Questions for discussion

Q. Based on this case report would you say that fetal cell transplantation worked to some degree? Explain your answer and suggest improvements that could ensure greater success. In their conclusion the authors say: “This study indicates that the mechanisms responsible for initiating the degenerative process are still present at this late stage of the disease and are capable of affecting grafted neurons.” Describe two equally likely explanations for how the transplanted tissue could prematurely develop Lewy bodies.

A. Yes, at least the grafted cells survived and appeared to be dopaminergic. The patient was reported to have improved phenotypically for a few years after the transplant before declining again. To ensure greater success, it would be great to CRISPR edit the graft cells to knock out alpha synuclein, but of course at that point you’d be talking about transplanting iPS, which was less successful in [Emborg 2013] below, rather than primary fetal tissue. I do think the authors’ conclusion is the parsimonious one, in light of all the other evidence for alpha synuclein behaving like a prion. But two other explanations for their data would be (1) that the aggregates in grafted cells are composed entirely of host-expressed synuclein, and/or that (2) some amorphous “toxic environment” of the diseased brain triggered the aggregates as a secondary effect and they are not actually central to the disease pathogenesis.

Emborg 2013: Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neural cells survive and mature in the nonhuman primate brain

This study describes the results of autologous stem cell transplantation into three nonhuman primates to replace neurons lost as a result of MPTP lesioning. An oft-cited previous study [Zhao 2011] had found that iPS-derived teratomas induced immune response in mice, whereas ESC-derived teratomas did not, suggesting some particular immunogencity of iPS. In the present study, Emborg et al created fibroblast-derived iPS, reprogrammed with lentivirus and labeled with GFP, and differentiated them into neurons, astrocytes and neural progenitor cells. They then created dissociated cell suspensions and grafted them into monkeys that had previously been subjected to MPTP injection to lesion dopaminergic neurons. In contrast to the teratomas of Zhao et al, Emborg found that six months after transplantation, the cells engrafted successfully and elicited minimal gliosis and no macrophage infiltration, indicating they were not being rejected. The cells contained a mix of astrocytes and neurons and the neurons had long projections. However most of the neurons were GABAergic, and only a minority were positive for TH (tyrosine hydroxylase, an enzyme required for dopamine synthesis in dopaminergic neurons), indicating they had not achieved replacement of the dopaminergic neurons lost due to MPTP lesioning.

This paper was important as it provided the first evidence that autologous iPS transplantation in primates could proceed without immune rejection.

Questions for discussion

Q. Explain how MPTP causes a Parkinsonian-like disease. What are the pros and cons of using the MPTP model?

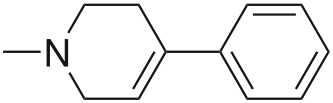

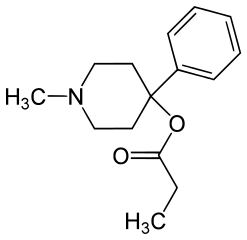

A. MPTP is a neurotoxic small molecule that specifically kills dopaminergic neurons:

MPTP is taken up by glia and metabolized into a molecule called MPP+ which is a substrate for import into dopaminergic neurons by the dopamine active transporter (DAT). Once inside the cell, it appears to poison cellular metabolism, at least partly by disruption of Complex I in the mitochondrial electron transport chain. MPTP is sometimes produced as an accidental byproduct in the synthesis of MPPP or desmethylprodine, which is this:

MPPP is a synthetic opioid and a recreational drug of yesteryear. People who used MPPP contaminated with MPTP developed parkinsonism (tremor, stiffness and bradykinesia). After that, some researchers started injecting MPTP into the brains of animals in order to model parkinsonism. Such “chemical lesion models” have been used in other diseases as well - for instance, kainic acid-lesioned rats have been used as a model for Huntington’s disease [reviewed in Kim 2011]. Because these chemical lesion models do not recapitulate the molecular cause of neurodegeneration in humans, I am generally of the opinion that they can be useful for neurobiology or studying disease symptoms, but are pretty useless for most molecular biology purposes (unless you are trying to model MPTP-induced parkinsonism, that is). However, while MPTP obviously fails to model the underlying disease process of Parkinson’s disease, it is useful in several ways: MPTP-lesioned animals respond to L-dopa, have lesions preferentially in the substantia nigra and less so in other dopaminergic neurons, and the susceptibility increases with the age of the animal. In fact, there is even some evidence that MPTP induces alpha synuclein aggregation [Kowall 2000] and that Snca knockout mice are less susceptible to MPTP toxicity [Dauer 2002].

Regardless, there is one area in which chemical lesion models can clearly be useful: in modeling autologous iPS transplantation to replace lost neurons. If you just want to see whether the transplanted neurons will be accepted by the host and will differentiate properly, it doesn’t matter as much how the original neurons were lost. And that’s exactly what they do in [Emborg 2013]. Even here, the model lacks a critical piece of Parkinson’s disease pathology - the cell-to-cell transmissibility of alpha synuclein aggregates - which as we saw in [Kordower 2008] is a major potential obstacle to cell replacement strategies. Therefore, this study can address questions like “will the transplanted neurons be rejected in a non-human primate?” and “will the neurons differentiate properly?” but it cannot address the question “will the neurons alleviate symptoms of Parkinson’s disease in the long term?”.

Q. Describe the major differences between the transplanted cells used in this study versus those used by Kordower et al. Explain why the authors generated iPSC lines that express GFP? Explain why the authors observed good graft incorporation, but no functional improvement?

A. These were autologous; Kordower used heterologous grafts. These were iPS, Kordower used fetal tissue. GFP was used to mark the transplanted cells. The lack of funcitonal improvement could be due to the low number of cells (on the order of tens of thousands, though I’m not sure what scale one would hope for) and/or the fact that most of the grafted neurons became GABAergic instead of dopaminergic.

Luk 2012b: Pathological α-synuclein transmission initiates Parkinson-like neurodegeneration in nontransgenic mice

This paper demonstrates that &alpha-synuclein fibrils formed in vitro transmit a synucleinopathy to wild-type mice. While the transmitted disease is not fatal, it results in formation of alpha synuclein aggregates, and ~35% loss of substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons by 180 days post-inoculation. Importantly, this paper shows several things which would be expected, based on the PrP literature, if alpha synuclein is indeed a prion: pathology was progressive (comparing 30, 90 and 180 dpi), appeared to spread outward according to neural connectivity, was less severe in Snca hemizygotes and absent in Snca knockout mice, and was specific to fibrils of alpha synuclein and not alpha synuclein monomers.

Although Virginia Lee had previously shown similar results in transgenic mice overexpressing mutant human alpha synuclein [Luk 2012a], people had the standard objections to that work: “but the Tg mice get sick anyway, so you’re just accelerating and not causing a disease process” and “maybe it’s an artifact of overexpression”. These sorts of objections have been raised against experiments demonstrating prion transmission in Tg animals for 20 years - at least since [Hsiao 1994].

Questions for discussion

Q. Where and to what degree is α-synuclein expressed endogenously? What is its normal function? What happened in a previous study in which synthetic preformed fibrils (PFF) of α-synuclein was injected into mice transgenic for PD-mutant human α-synuclein? What were the limitations of this study? Why did the authors think that these experiments were worth trying in nontransgenic mice?

A. In humans, SNCA mRNA is expressed throughout the brain, fairly highly in the substantia nigra though it is actually highest in the cortex [GTEx Portal]. Its normal function is unknown. The Tg mice from [Luk 2012a] actually express “mutant” human alpha synuclein under the PrP promoter. I say “mutant” in quotes because although the A53T mutation is pathogenic in humans, it is actually the reference sequence in endogenous mouse Snca. In my summary above I mentioned some of the standard objections that prionologists raise to Tg mouse experiments. Of course Virginia Lee wanted to go for the gold: prion-like transmission in wild-type animals is always going to convince more people than experiments in transgenic animals.

Q. Describe anatomical distribution of hyperphosphorylated synuclein deposits after the injection of PFFs into the dorsal striatum. What is the evidence that these deposits are like Lewy bodies of PD? That the distribution is connectivity dependent?

A. The evidence for connectivity is:

Additional populations, such as the contralateral neocortex, also developed LBs/LNs indicative of progressive spread to CNS regions… Mapping of pSyn pathology in mice at 30, 90, and 180 dpi (Fig. 1G) revealed a time-dependent dissemination of LBs/LNs between 30 and 180 dpi, with sequential involvement of populations initially unaffected at 30 dpi, including ventral striatum, thalamus, and occipital cortex, along with commissural and brainstem fibers.

The ventral tegmental region is adjacent to the substantia nigra and is also dopaminergic, but is not functionally connected. It was minimally affected. This is further evidence for connectivity being important.

The evidence for the deposits being “like Lewy bodies” is (I think) simply that they were positive for alpha synuclein.

Q. What is the significance of the development of synuclein pathology in the substantia nigra pars compacta? What is the evidence that synuclein deposition is linked to loss of dopaminergic neurons? In what ways do the motor and behavioral characteristics of the mice resemble that seen in PD? In what ways do they not?

A. Overall, the deficits in the mice were less severe than in Parkinon’s patients - only 35% dopaminergic neuron loss, and although they had poorer rotarod performance they had unchanged open field performance. But this is 6 months after inoculation, and in humans the disease develops after decades of life. I’d say the evidence that the synuclein deposition is linked to neuronal loss is that synuclein deposition was seen in the mice inoculated with fibrils but not with monomers or saline, and that neuronal loss was also seen only in the mice inoclulated with fibrils. Also the fact that hemizygotes were less affected and Snca knockouts were unaffected.

Q. What other experiments might further address the question of whether misfolded/aggregated synuclein is in fact transmitted from neuron to neuron?

A. This study was seminal, and convinced many doubters that alpha synuclein really is a prion. To me, this study has already conclusively demonstrated that the misfolded synuclein is transmitted neuron-to-neuron. They inoculated just 5 μg of fibrils in 10 μL of liquid, and induced a progressive spread of pathology over six months. This can’t just be due to progressive internalization of the inoculated fibrils, because pathology was absent in Snca knockout mice. And it can’t be due to some vague “neurotoxic insult” of the inoculation because alpha synuclein monomers did not induce pathology. I assert that nothing other than cell-to-cell transmission of misfolded protein can explain the data in this paper.

An additional experiment you could do would be to do the classic [Brandner 1996] experiment but for synuclein instead of PrP. Graft a piece of synuclein-expressing tissue into Snca knockout animals and then try to infect the graft with PFFs. One would hypothesize that only the synuclein-expressing neurons will develop Lewy bodies and/ors die.