Organic chemistry 04: Arrow-pushing: resonance, nucleophiles and electrophiles

These are my notes from lecture 4 of Harvard’s Chemistry 20: Organic Chemistry course, delivered by Dr. Ryan Spoering on February 2, 2015.

Resonance

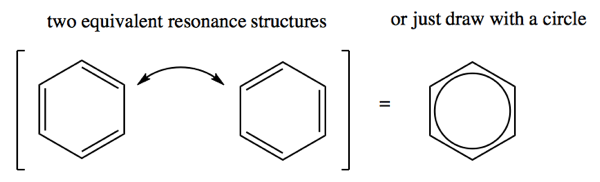

Equal resonance

The structure of benzene frustrated chemists surprisingly far into the 1900s. Each side of the hexagon is 1.4Å, about halfway between the C-C bond length (1.54Å) and the C=C bond length (1.34Å). Benzene can be drawn with a resonance structure of two different configurations of the double bonds. For a long time, chemists debated whether there were indeed two separate species in equilibrium with each other. It was eventually determined that is not the case - there is in fact but a single benzene structure, which is a superposition of those two structures. Thus, drawing it with a circle in the middle is actually more accurate to how benzene behaves on its own. Yet the circle model makes it confusing to account for electrons when thinking about reactivity.

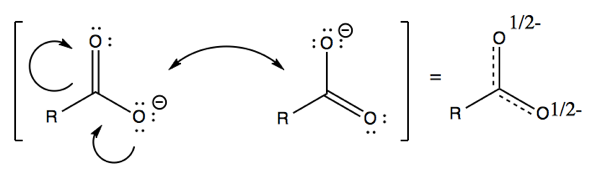

Another example of resonance is carboxylate ions. Here, the small curvy arrows indicate resonance between electrons on lone pairs of oxygen, and electrons in pi bonds. In other words, both oxygens have half the character of having two lone pairs, and half the character of having three lone pairs, and both carbon-oxygen bonds have half the character of a single and half the character of a double bond. Just as in benzene, the two structures are equivalent and equal contributors to the one actual structure.

Note that the small arrows must always point from a place that has electrons to a place that can accept electrons.

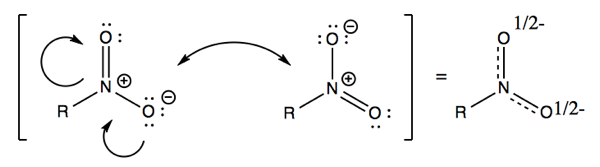

A final example is nitrites. Once again, the two structures are equal contributors.

In all of the above examples, there is actually but one structure, and it just takes two drawings of structures to explain what that one structure is.

Unequal resonance

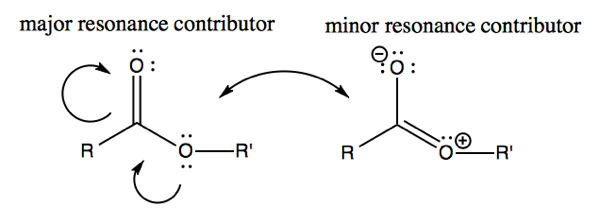

Esters have an unusual property that is not fully captured in the drawing. There is one structure which has no formal charge and is thus more stable. However, some of the reactivity of esters can only be explained by invoking some amount of electron donation which creates a formal charge. Thus the structure at left is the major contributor, while that at right is less stable, and is a minor resonance contributor.

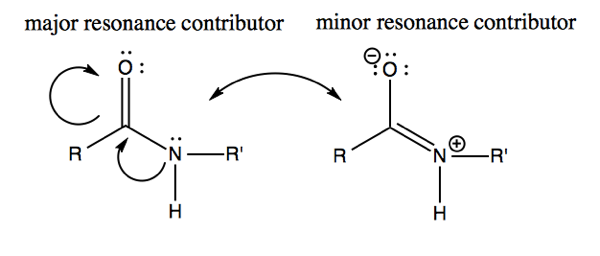

Similarly in amides, there is a barrier to rotation around the carbon-nitrogen bond created by the partial double bond character of the minor resonance contributor at right. This is an important factor in protein folding.

Stabilization by multiple minor resonance structures: the example of alcohol deprotonation

An alcohol such as methanol (CH3OH) has a pKa of ~15, about the same as water itself. Thus, the forward direction of this reaction has a very unfavorable Ka of 10-15:

CH3OH + H2O ↔ CH3O- + H3O+

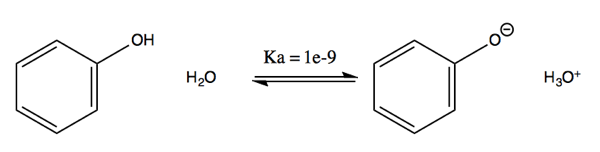

A phenol on the other hand has a pKa of ~9, meaning it has about 106 greater propensity to dissociate into acid in water than methanol does.

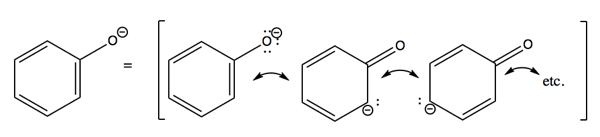

This greater stability can be explained by resonance. When the -OH on phenol is deprotonated to leave O-, the extra electron density on that oxygen is shared into the pi system of the benzene ring. This greater distributedness of electron density is more favorable than having only the one methyl group in methanol to share that electron density with. Mind you, oxygen is more electronegative than carbon, so in either case, the resonance structure in which oxygen has the extra electron is always the major resonance contributor. But phenol has six minor resonance contributors corresponding to the charge being on each different carbon, whereas methanol has just one minor resonance contributor. And phenol’s minor resonance contributors involve a double bond to oxygen instead of in the aromatic ring. Thus, in the phenol conjugate base, known as phenolate, oxygen and all carbons are sp2.

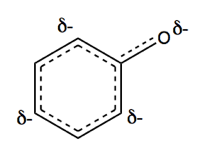

We can draw a single structure with dotted lines that sort of reflects this, with δ- indicating partial negative charge:

Nucleophile-electrophile reactions

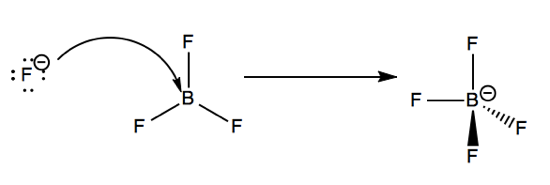

We’ll begin with a Lewis acid-base reaction. BF3 is a trigonal planar electron receptor due to its incomplete octet - it has one empty 2p orbtial. F- is an electron donor. The reaction between these two species can be accounted for by an arrow indicating the movement of lone pair from F- into that empty 2p orbital. This results in a tetrafluoroborate ion with tetrahedral shape, and a formal negative charge on boron.

Frontier molecular orbital theory

In frontier molecular orbital theory (FMO), a reaction is when a filled orbtial → empty orbital.

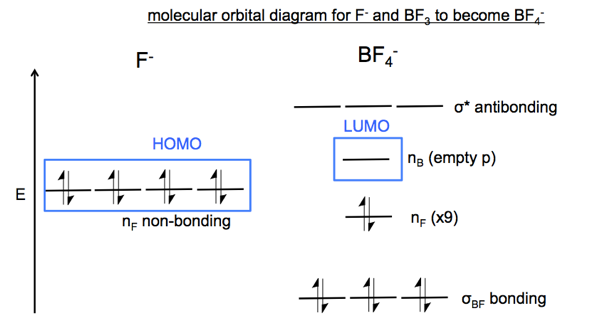

In the example above, the fluoride ion has four filled non-bonding orbitals, denoted nF (n for non-bonding, F for fluorine). BF3 has an empty non-bonding orbital on boron dubbed nB. The mixing of the filled orbital nF into the empty orbital nB yields the BF4 ion.

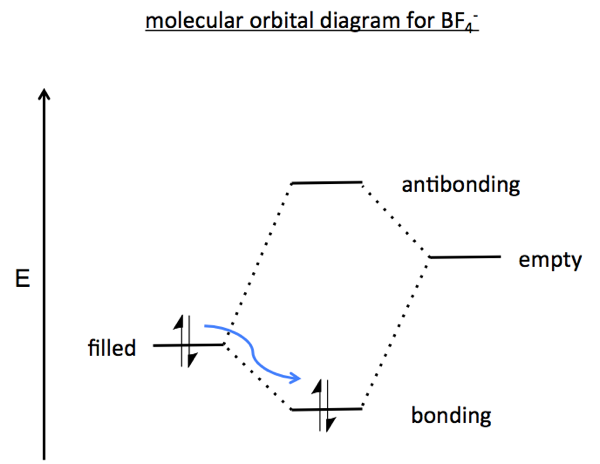

These sorts of filled-empty interactions create one lower-energy bonding orbital and one higher-energy antibonding orbtial. From the diagram below, you can observe that if you had a filled-filled interaction you would have surplus electrons leading to a filled antibonding orbital. If you had an empty-empty interaction there would be no electrons to fill the bonding orbital. This diagram depicts what happens when the fluoride ion and BF3 meet:

HUMO-LUMO

Frontier molecular orbital theory holds that the interactions all take place at the frontier or marginal orbitals. In other words, to understand the entire reaction, you only need to consider the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO). In order for a new bond to form, two conditions must be met:

- Spatial overlap between HOMO and LUMO

- Energetic similarity between HOMO and LUMO

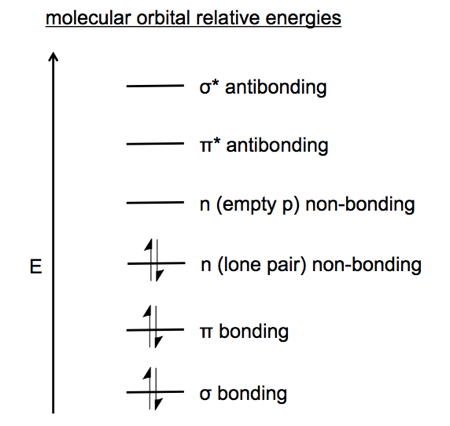

The most stable bonds in a molecule are σ bonds. These offer a lot of stabilization relative to non-bonded atomic orbitals. π bonds are the next lowest energy, then lone pairs denoted n for non-bonding, then empty p orbitals denoted n for non-bonding, then π* antibonding, then σ* antibonding.

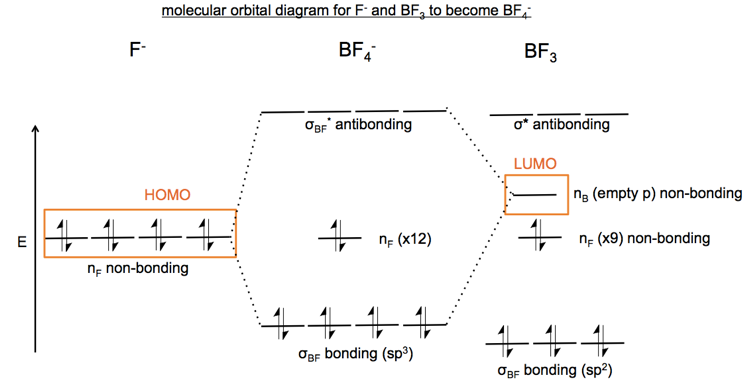

With this insight, we can draw a full MO diagram of the reaction between F- and BF3. I am not certain I got all the details correct but here is my best attempt:

The reaction involves the movement of electrons from an nF non-bonding orbital in F- to an nF non-bonding orbital in BF4-. Because movement is between non-bonding orbtials, this is called an n→n reaction.

I don’t fully understand this because it seems like once you have formed a tetrahedral BF4- ion you have four sp3 hybridized orbitals rather than three sp2 hybridized orbitals and you have therefore moved electrons from a non-bonding orbital into a bonding orbital. If so, then the MO diagram should look more like the one below. I need to ask about this in class.

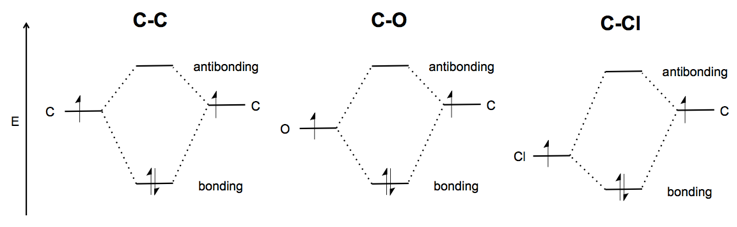

Electronegativity

The relative electronegativity of the two atoms bonding determines the relative energy difference between a σ bonding orbital and a non-bonding orbital from the more electronegative atom. Carbon-carbon is symmetric, whereas in carbon-oxygen the oxygen’s non-bonding orbital is lower, and in carbon-chlorine, where the latter is quite electronegative, the picture is more lopsided still.