Protein folding 03: Beta sheets

These are my notes from week 3 of MIT course 7.88j: Protein Folding and Human Disease, held by Dr. Jonathan King on February 19, 2015.

Assignment 2

The reading for this week was [O’Shea 1989] as well as chapters 4-5 of Branden & Tooze.

Alpha/beta structures

α/β structures are common to many small molecule-binding enzymes, including all of “glycolytic” enzymes (which bind and break down glucose in glycolysis). In such a structure, there is a core β-barrel consisting of several beta sheets, either all parallel or mixed parallel/antiparallel, surrounded by a cage of alpha helices. In linear sequence, the alpha helices and beta sheets alternate. Thus, you can think of the structure as being made up of repeating αβα motifs. It is actually the loops at one end of the barrel that form the active site for binding the small molecule.

Current phylogenetic evidence suggests that the 15 or so distinct proteins known to have alpha/beta structures arose by convergent evolution. However, interestingly, in parallel beta barrels, the active site is always at the end that has the C terminus of each beta strand, and there is no obvious reason why this should need to be the case. There is one theory out there about charge having something to do with it.

From leucine zipper to coiled coil

By the late 1980s, the “coiled coil” introduced last time was already understood to be the structure of fibrous proteins like tropomyosin and keratin. Landschulz et al studied the DNA-binding protein GCN4 and proposed that its structure was a “leucine zipper” in which the leucines, which repeated every 7 residues, interlocked [Landschulz 1988]. O’Shea et al responded with evidence that GCN4 is in fact also a coiled coil, a structure which shares some structural features with the proposed leucine zipper but does not have leucine interdigitation [O’Shea 1989].

It is worth recapping the major arguments of the 1989 paper one by one. O’Shea created 33-residue synthetic peptides corresponding to the proposed leucine zipper region of GCN4. In this paper, they did not yet determine a high-resolution structure - that came a few years later [O’Shea 1991] - but they used several clever experiments to narrow down the range of possible structures. First, they settled on some basic aspects of the structure:

- Circular dichroism (introduced here) indicated 100% alpha helical structure. Note, however, that because they later show that the peptide spontaneously forms dimers in solution, all this really shows is that the dimer is alpha helical - it is impossible to tell what structure the monomer has. In fact, Prof. King believes that the dramatic decrease in θ 222nm signal in the CD spectrum of Fig 2B as you heat the protein suggests a loss of alpha helical content when you dissociate the dimers. This is an important lesson that you cannot dissociate secondary structure from tertiary struture.

- The melting point depended on peptide concentration, which meant the peptide must form dimers or higher-order oligomers. They cite another group’s sedimentation experiments showing that it is in fact a dimer.

- The peptide is highly soluble, indicating the hydrophobic side chains must be buried in the helix-helix interface.

Then they tackled their core question of whether the helices were arranged in a parallel or antiparallel fashion. To do this, they synthesized 36-residue peptides with the original sequence plus CGG at the N terminus or GGC at the C terminus. The glycines allow flexibility so that the cysteine can form disulfide bonds under oxidizing conditions. They could distinguish the C-terminal homodimers, N-terminal homodimers, and heterodimers, on HPLC, even though the molecular weight for all is the exact same. Prof. King explained in class that the C versus N-terminal disulfide bond and parallel versus antiparallel configurations result in differential neutralization of charged residues along the helix, which affects migration of the dimer on HPLC.

In any event, they observed:

- In oxidizing conditions, one could readily obtain homodimers (N-N or C-C disulfides) whereas heterodimers were rarely recovered, indicating that the parallel configuration was preferred for the folded protein.

- In conditions that were both oxidizing and denaturing, it became possible to obtain heterodimers, indicating that the unfolded protein was capable of forming heterodimers. This seems to be a sort of control for the above bullet point.

- Once formed, the homodimers had a melting temperature that was independent of concentration, consistent with covalent association. The heterodimer had a lower, and still concentration-dependent, melting-point. (I don’t understand why this supports their theory; the heterodimer, though harder to form, ought to still be covalent, no?)

- If they formed heterodimers in denaturing conditions and then added them to a redox buffer (presumably diluting away the denaturant?), they went away, while the homodimers stayed. Thus the homodimer was preferred.

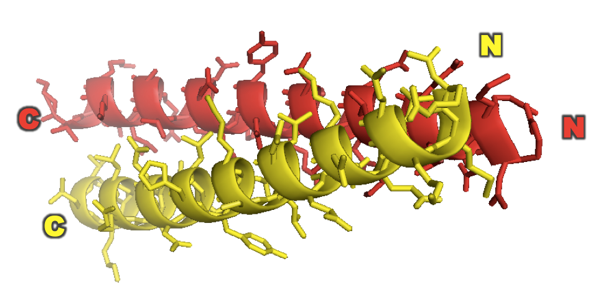

Based on all of this they conclude that GCN4 forms a parallel coiled coil. This was shown even more definitively when they came out with their X-ray structure of it two years later [PDB# 2ZTA, O’Shea 1991]:

fetch 2zta

hide everything

show cartoon

color red, chain A

color yellow, chain B

bg_color white

show sticks

Lecture: all beta sheets, all the time

Historical perspective on our understanding of globular proteins

In the early days of protein biochemistry, there were two camps. One camp was interested in food science and spent a lot of time studying egg white albumin and proposed an “oil drop” model of flexible polypeptides floating around in solution. The other camp spent a lot of time on fibrous proteins such as keratin and tropomyosin, and thought of proteins as being densely packed solids. Crystal structures couldn’t resolve this issue because crystallization inherently involves pushing things close together.

The controversy was finally resolved in a paper entitled The interpretation of protein structures [Richards 1974]. Packing density is a dimensionless quantity, the ratio of volume of objects to the total volume of the container they are in. Or as the size of the container goes to infinity, I guess it’s just the ratio of volume of objects to total volume occupied including the dead volume. For spheres in a box, the closest packing has a density of 0.74, for cylinders, it’s .91, and for crystals of organic small molecules (including benzene) the range is 0.70 to 0.78. In 1974, only three protein structures had been solved to high resolution: egg white lysozyme, ribonuclease, and myoglobin. Richards first determined the Van der Waals volumes of each amino acid (analogous to the spheres in a box). Then, to infer the “total” volume of the protein (analogous to the box itself), he modeled them as Voronoi polyhedra. In the Voronoi model, first you draw line segments between the centroid of each pair of adjacent amino acids, then you draw equal length line segments perpendicularly bisecting those line segments, then you draw a box that contains all of the line segments. Using this method, Richards computed the packing density of egg white lysozyme at 0.75 and of RNAse at 0.74. This was a profound result. These figures were within the range of crystallized organic small molecules, such as amino acids. In other words, the packing of amino acids in protein was about as dense as the packing of amino acids in crystals. Interpretation: proteins are just about as dense as can be.

Richard revolutionized our understanding of proteins. Yet it was not immediately clear how to reconcile the idea of a protein packed as densely as a crystal with the knowledge that proteins had to change conformations to do their jobs. Enzymes, for example, had to be flexible enough accommodate a small molecule, move it over the energy barrier to catalyze a reaction, and then release it.

The next breakthrough came from the lab of Barry Honig, best known as an expert in electrostatics and ionic bonds in proteins, in a paper entitled Internal cavities and buried waters in globular proteins [Rashin 1986]. These researchers modeled water as a sphere with a 1.4Å radius, and then analyzed proteins that had known structures with cavities. They asked how many water molecules you could fit in the cavity.

| protein | size (kDa) | # of cavities | total # of H2O |

|---|---|---|---|

| bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor (BPTI) | 6 | 2 | 4 |

| cytochrome C | 11 | 5 | 2 |

| RNAse | 13 | 5 | 1 |

| lysozyme | 14 | 8 | 5 |

| myoglobin | 17 | 23 | 1 |

| trypsin | 23 | 13 | 17 |

These proteins were just a few example of what eventually proved to be a general rule: globular proteins almost never have holes in them that are large enough to hold bulk water, meaning, water that can move around. Instead, hydrophobic residues are packed into the center, excluding bulk water by hydrophobic effect. These six proteins, and many others, do hold just a few water molecules, but they are each hydrogen bonded to the side chains. The pockets where the waters were predicted to reside were not accessible from the surface by any water-sized channel. But, they were connected to the surface by channels that are smaller than the size of a water molecule, and the places where water resided were generally near active sites. Thus, these channels may have opened just wide enough to allow individual water molecules to come in and out in some conformations of the protein but not others.

In multi-domain proteins, sites that hold water are almost always between domains. This is consistent with the view that multi-domain proteins may have evolved through gene fusion.

We now accept as a general rule that globular proteins have a hydrophobic interior and charged or polar exterior. 96% of R and K residues have side chains sticking outwards into solvent.

Quick review of alpha helices

Recall a few key points from last time:

- The core of an alpha helix is perfectly Van der Waals packed, accommodating no water at all.

- All side chains stick outward.

- Alpha helices can accommodate any amino acid sequence. Although there are motifs enriched in alpha helices and there are bioinformatics tools that predict alpha helices based on this, no sequence is a perfect negative predictor of alpha helical conformation.

Beta sheets

A beta strand is essentially a helix with 2.0 residues per turn, and a rise of 3.5Å per residue. Every other side chain points forward, backward, forward, backward. A beta sheet is made up of multiple beta strands, often not consecutive in linear sequence. No reported protein structure has ever had an isolated, naked beta strand - they always come in sheets. Beta sheet-rich proteins are the proteins for which it is most difficult to understand how sequence dictates fold, and even in cases where chaperones are known to have a role, it is hard to figure out exactly what the chaperone does. In general, careful inspection of beta sheet-rich proteins yields no insight as to how they fold.

Famous superstructures of beta sheets include Greek key and propeller. Some of the most satisfying strucutres are those of transmembrane channels, where the beta sheets form a barrel that transverses the membrane.

In a parallel β-helix fold, the same motif repeats in a regular fashion [Jurnak 1994, Yoder 1993, Emsley 1996]. Such proteins are found almost exclusively in pathogens, and often the sides of the beta sheets form a long lateral surface that recognizes specific glycans on the host cell. There is evidence that beta helices have been selected against in evolution, probably because they are incredibly prone to off-pathway aggregation.

As an example of a β-helix, here is the Bordetella pertussis virulence factor P.69 pertactin [PDB# 1DAB] from [Emsley 1996]:

fetch 1dab

bg_color white

hide everything

show cartoon

spectrum count, yellow_red

When an alpha helix is packed against a beta sheet, the angle between them is usually within ±30°. This is thought to be explained by the complementary twist model. All known beta sheets have a right-handed tilt of about 18-19° per strand. It is not entirely clear why these are always right-handed, though it must in some way relate to amino acids being left-handed. The grooves in beta sheets are thus perfect to accommodate the ridges formed by the i, i+5, i+8, i+1, i+5 and i+9 residues of an alpha helix, with perfect Van der Waals packing.

When a protein contains multiple beta sheets, they are almost always found with sheets (nearly) “parallel” to each other (~-30°) or with sheets nearly perpendicular to each other (~-90°). The former includes “β-pleated sheet sandwich” proteins such as concanavalin A and superoxide dismutase (SOD1). For examples and diagrams see [Chothia & Janin 1981].

For years, people suspected that the side chains sticking out in front and behind the beta sheets, which were involved in the packing between beta sheets, must help drive the folding of the protein into beta sheets to begin with. However, in a very close look at several known beta sandwich proteins, it was impossible to identify any side chain-specific interactions at the interfaces between beta sheets [Chothia & Janin 1981]. Instead, I, L, F and V comprised 61% of all residues at the interface, consistent with exclusion of water due to relatively nonspecific hydrophobic interactions.

The situation with perpendicular beta sandwiches is similar, except that they have two “splayed corners” where there may be other interactions.

The most important beta sheet-rich proteins in our daily life are immunoglobulins.

Folding intermediates

It is hard to even imagine by what series of steps the complicated beta sheet-rich proteins might fold. In order to study the folding process of any protein - from fully denatured polypeptide to native state - you need some way of characterizing the intermediates along the pathway. The tools for this are usually:

- Circular dichroism

- Fluorescence*

- NMR

- H/D exchange

Note that X-ray crystallography is not on the list because it is usually impossible to crystallize an intermediate.

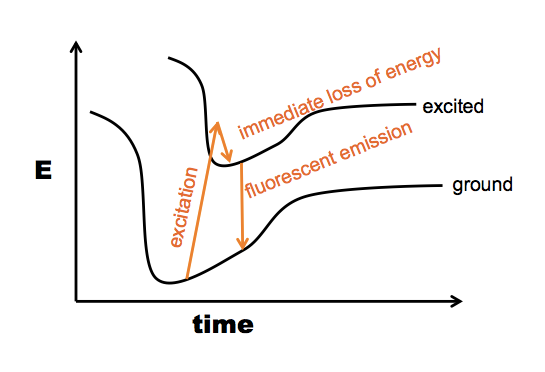

*Here is a further note about the “fluorescence” option. This actually uses the same principle as measuring protein concentration on the NanoDrop. Proteins absorb UV light with a peak absorbance at 280nm due first and foremost to tryptophan (W), although W is rare and some proteins don’t have a single W residue. Y also absorbs at 280 nm, though several times less. F has a peak closer to 260 nm, and its 280 nm absorption is barely on the chart. Anyway, the principle is that when any of these residues absorbs a photon, the excited state will within 1e-15 seconds lose some of its energy again and go back down to the lowest excited state. If this doesn’t chemically change the molecule, the next step is it will usually fall back to ground state, emitting another photon - but because it already lost a little bit of energy, the emitted photon has a lower wavelength than the absorbed photon (represented here by a slightly shorter arrow):

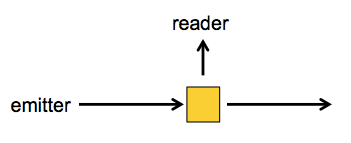

Usually, when you do excitation-emission measurements, you have the sample in a cuvette, and you shine the excitation photons in a tight beam from one angle, whereas the emitted photons will come off at any which angle, so you have the measuring device orthogonal to the excitation beam:

So when you’re using the NanoDrop you are measuring absorbance, but if you want conformation information, you can also measure emission. When W is in an unfolded protein, its λmax (peak emission wavelength) is at about 350 nm, and when it is buried in the hydrophobic core of a protein, its λmax drops to 330 nm.

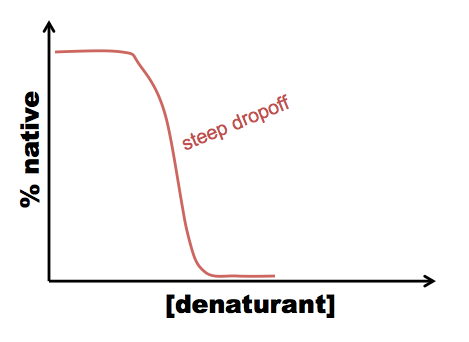

A typical procedure to gain conformational information about intermediates is either equilibrium folding, in which you start with your protein in a very strong denaturant, say, 8M GdnHCl, and serially dilute it into 6M, 4M, 2M, 1M GdnHCl and so on - or equilibrium unfolding in which you start in a native buffer and add denaturant. Either way, you’ll likely see a peak at 350 in your 6M GdnHCl solution, but at 330 in your lowest GdnHCl solution. In between, you can quantify the extent of protein folding by calculating the absorbance at 330 nm as a proportion of the absorbance at 330 nm in the native state. For most proteins, what has been discovered is that folding is a cooperative process, resulting in a relatively steep dropoff from native to denatured state:

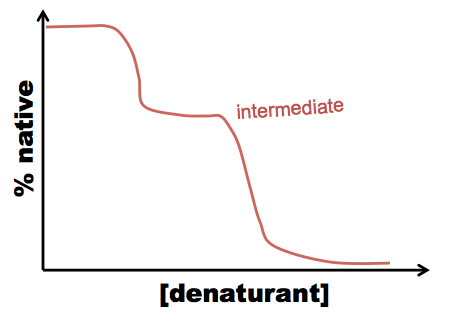

This allows you to calculate ΔG, but tells you nothing about the mechanism of folding. However, sometimes you see a curve more like this:

In this case, there are two processes: N ↔ I, and I ↔ U (N = native, I = intermediate, U = unfolded), and you can figure out how much the tryptophan is buried in the intermediate state.

If you measure enzymatic activity and fluorescence of a protein in various denaturant concentrations, you sometimes see a tight relationship between the two: native protein has activity, denatured protein does not, plain and simple. Other times, the two are uncoupled at certain intermediate concentrations, indicating that a partially folded intermediate may retain enzymatic activity but expose its W residues, or vice versa.

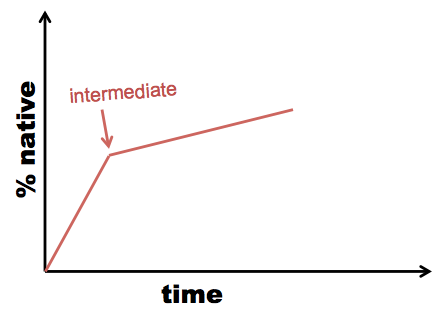

Sometimes re-folding takes time, not just dilution of denaturant. In this case, you need to measure UV emission (or another readout) over time within each dilution. This is called kinetic refolding or kinetic unfolding as opposed to equilibrium refolding and unfolding. When you see an inflection point in your kinetic curve, it suggests the existence of an intermediate:

Example: the lens protein gamma D-crystallin

The γD-crystallin in your lens was translated by a ribosome when you were in the womb and deposited in what became your lens. This initial supply of the protein lasts your entire life - your lens has no nuclei so it cannot produce more crystallin. This protein is therefore among the longest-lived of proteins. These proteins have a ton of tryptophan in them, because the retina is highly sensitive to UV light. The lens functions to protect the retina from UV light, while being perfectly transparent in the visible spectrum. Note that W only sometimes emits a photon when excited - the rest of the time, the indole ring is broken instead, and the amino acid you now have is no longer quite tryptophan. γD-crystallin has a structure exquisitely evolved to shunt excitatory energy away from its tryptophans, so that the protein will not be destroyed by years of exposure to UV radiation. As a result, the tryptophans are much brighter than tryptophans in most proteins.

This protein provides a great example of folding through intermediates. It has four W, and by making a series of mutants where all but one of them were substituted by F, Jonathan King was able to measure the refolding kinetics for each individual tryptophan. The data indicate that C-terminal tryptophans resume native state fluorescence much quicker (on the order of 15 minutes faster) than N-terminal tryptophans, suggesting that the protein folds sequentially from its C terminus [Kosinski-Collins 2004]. The protein has two domains - C terminal and N terminal. King’s group made a series of mutations in residues at the interface between the two domains, and found that these did not affect the final, fully folded structure of the protein, but did affect the kinetics of folding - most of the substitutions increased the time required for folding by over 10x. Thus, the C terminus appears to act as a template for the folding of the N terminal part, and when this templating ability is lost, you have to wait much longer for the N terminal domain to fold on its own [Flaugh 2005a, Flaugh 2005b]. There are several pairs of aromatic residues pointed at one another in the beta sheets of γD-crystallin. Prof. King’s lab tried mutating each of these residues one by one [Kong & King 2011]. Predictably, most of the mutations affected the equilibrium unfolding curves. However, surprisingly, only one pair - Y133/Y138 - affected kinetic refolding. This is the most C-terminal of all of the pairs studied, and appears to nucleate early folding events in the C terminus.

Sea slugs or something have orthologs of γD-crystallin but with only one domain, whereas all vertebrates have a two-domain version. The two-domain version is thought to have been favored in the vertebrate lens due to higher stability.

Sometimes at very low denaturant concnetrations, where you are mostly in the native state, you will see a lot of noise in your UV spectra from aggregates. The aggregates have a locally native conformation, but are formed from intermolecular rather than intramolecular Greek keys. The aggregates quench tryptophan fluorescence but have a lot of conventional light scattering which introduces noise into the measurement.