Organic chemistry 11: SN1 Substitution - carbocations, solvolysis, solvent effects

These are my notes from lecture 11 of Harvard’s Chemistry 20: Organic Chemistry course, delivered by Dr. Ryan Spoering on February 25, 2015.

Unimolecular substitution reactions (SN1)

SN1 are the simplest type of reaction. It can proceed via solvolysis.

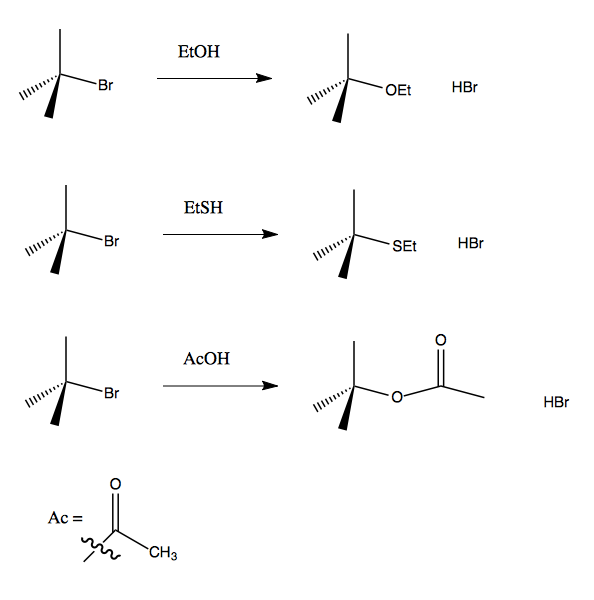

If you have a polar protic solvent, a carbon-halide bond will break very easily, yielding a carbocation which will rapidly react with solvent. All of these reactions with tert-butyl-bromide will run forward:

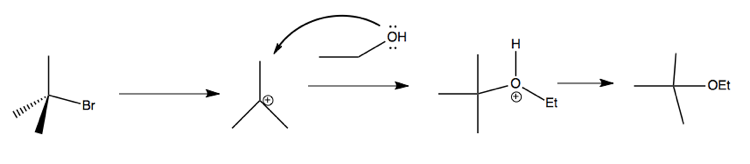

This proceeds via the a 2-step mechanism (this is what he said in class, even though it looks like >2 steps to me):

Review of molecularity and kinetics

| class | elementary steps of a reaction | rate = |

|---|---|---|

| unimolecular | A → B | k[A] |

| unimolecular | A → B + C | k[A] |

| bimolecular | A + B → C | k[A][B] |

| bimolecular | A + B → C + D | k[A][B] |

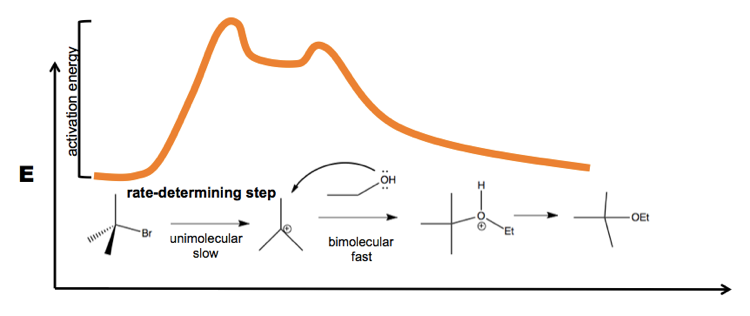

When you have a reaction with two steps, this gets complicated. But in the case of tert-butyl-bromide, the unimolecular step is so slow that to a close approximation, the rate depends only on that step. Therefore the overall rate for this reaction is k[+BuBr]:

Carbocation stability

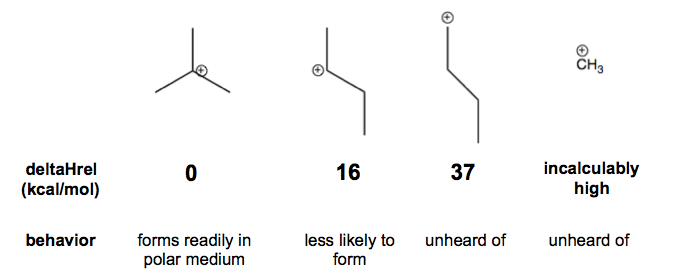

The more alkyl substitution there is on a carbon, the more stable the corresponding cation will be. That is because alkyl groups can donate some electron density to the carbon carrying the formal charge. Therefore a tert-butyl cation is by far the tertiary carbocation you are most likely to encounter. The two carbocations at right are so high-energy that you will essentially never encounter them as a plausible intermediate.

In tertiary carbocations, hyperconjugation is what helps stabilize. There is a weak donation of electron density from the σCH bond to the empty p (nC) orbital.

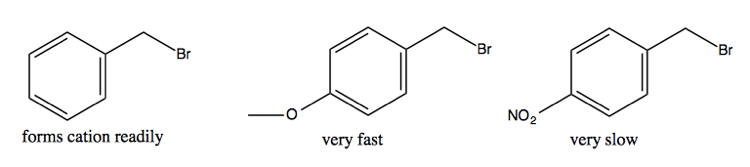

Here are some potential benzylic cations and their relative propensity to ionize:

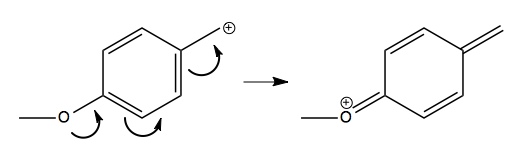

The reason why the middle one is so prone to ionize is because it has several resonance stuctures, one of which (depicted below at right) has all octets satisfied, which is the biggest determinant of stability:

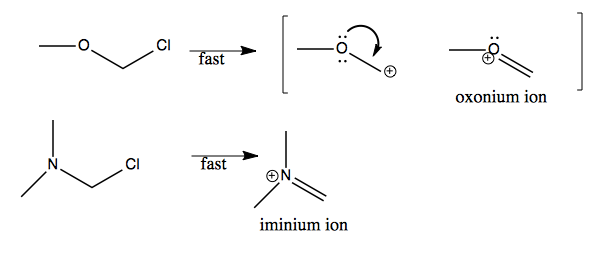

Indeed, lone pair donation from oxygen, or nitrogen, is a popular way of stabilizing carbocations, for instance in the two examples below, which yield oxonium and iminium ions.

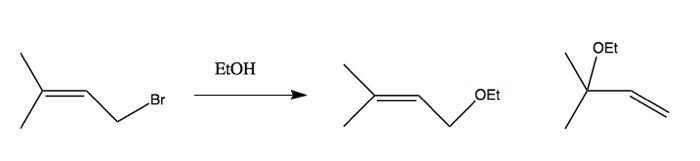

Allylic cations are also possible. For instance, this reaction runs forward:

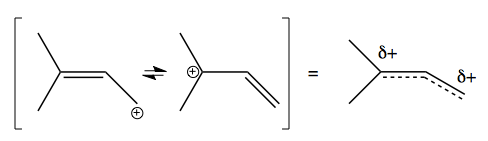

And the reason why the cation forms readily is that it has a resonance structure such that the positive charge is shared equally between two carbons:

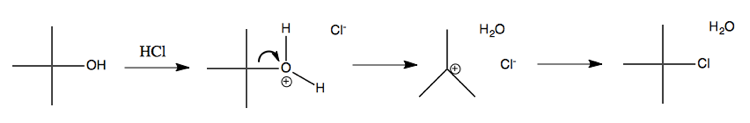

So far we’ve talked only about alkyl halides, which are useful commerically available reagents. However, carbocations also figure into plenty of other types of chemistry. In fact, using acid catalysis, you can easily achieve solvolysis of alcohols, and thereby make alkyl halides via an SN1 reaction known as acid-catalyzed dehydration:

Note that when you take a chiral molecule and put it through a unimolecular substitution with a carbocation intermediate, it loses its steochemistry because the carbocation is trigonal planar. If the end product is chiral again, you’ll end up with a racemic mixture, even though you started with 100% S or 100% R.