Organic chemistry 13: Bimolecular beta elimination (E2) - regioselectivity and stereoselectivity

These are my notes from lecture 13 of Harvard’s Chemistry 20: Organic Chemistry course, delivered by Dr. Ryan Spoering on March 2, 2015.

Bimolecular β-elimination (E2)

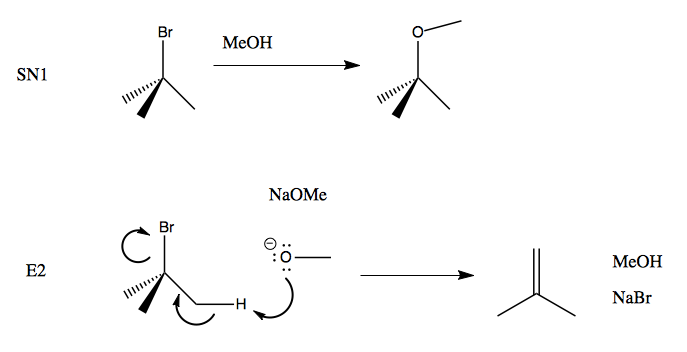

Recall that SN1 reactions proceed via solvolysis. A substrate very slowly dissociates to form a carbocation (that’s the rate-limiting step), which once formed is highly reactive and will react with even the weakest of nucleophiles. In the diagram below, the top reaction is an SN1. What if we want to speed it up? We can use NaOMe instead of MeOH, and then it will proceed via the bottom reaction, which is E2:

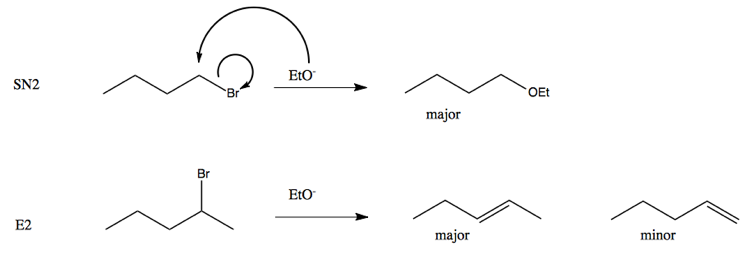

E2 reactivity depends on how basic the nucleophile. In many cases you get both a major and minor product. Consider the following SN2 vs. E2 reactions:

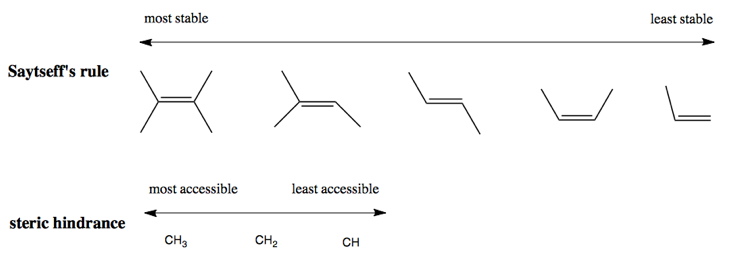

Regioselectivity

Saytseff’s rule says that the more substituted an alkene, the more stable it is. Most bases in E2 will preferentially form the most substituted alkeke possible (i.e. furthest left in the below diagram). However, there is a countervailing phenomenon as well. It is easier for E2 bases to go after hydrogens on less-substituted carbons. This is trivially due to the number of opportunies (CH3 has three hydrogens, CH has just one, so even if there were no preference, the base would get one of the methyl hydrogens 3/4 of the time), and less trivially due to steric hindrance - hydrogens on less-substituted carbons are more accessible.

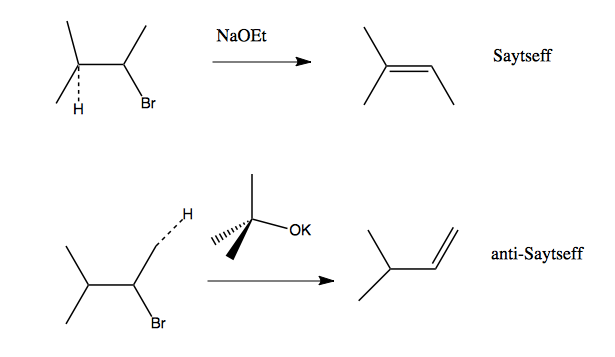

We can play these two countervailing trends against each other to get the product we want, using what we call regioselectivity. The following two reactions can be performed on the same substrate; the first product is by far the easier one to get, but by using a bulky enough base such as KOtBu, which we use in the second reaction, we can introduce enough steric hindrance to favor a different product. (The hydrogen being removed is shown with a dashed line).

Stereoelectronic effect in E2

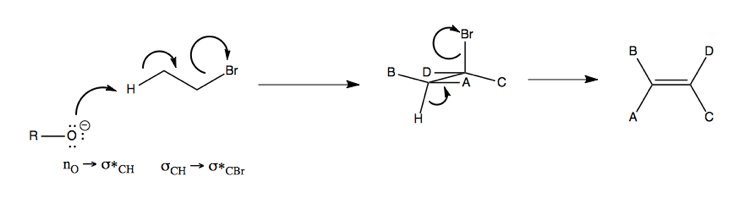

Consider the orbitals involved in an example E2 reaction. In order for the following reaction to be favorable, you need antiperiplanar CH and CBr bonds, or in other words, the hyrodgen and the bromine must be able to take on an anti position in the Newman projection of the molecule.

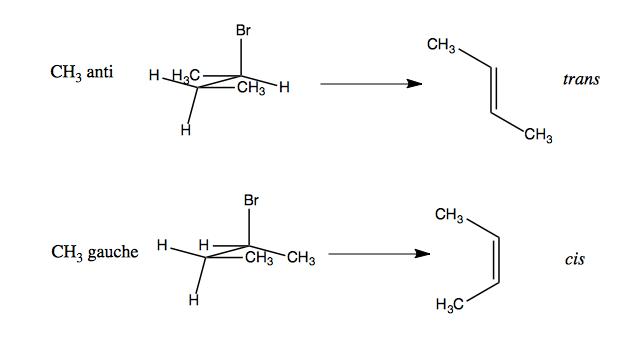

You can take advantage of this to get stereoselectivity. In the following example, observe how two different conformations of the reactant result in trans vs. cis isomers as the product. In this case, the CH3 anti conformation is far more favorable than CH3 gauche, and as a result, the trans product is vastly favored over the cis.

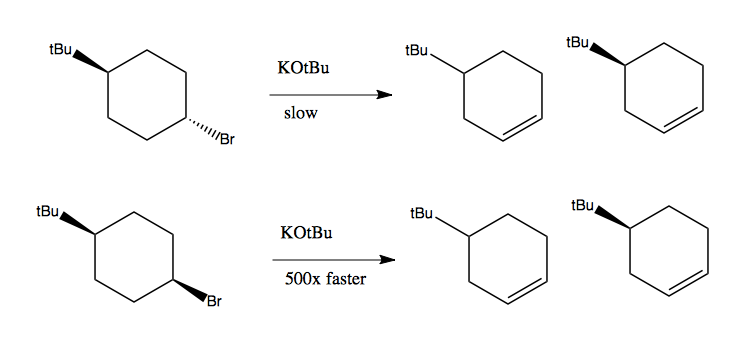

Below is another example. In both cases, we get a racemic mixture of the two enantiomers at right. Yet the second reaction runs ~500x faster than the first one. This is because in the bottom reactant, there are two antiperiplanar hydrogens, which have the necessary alignment to let this reaction run forward.

This can be understood by looking at the different chair cyclohexane conformations of these two molecules in diamond lattice form:

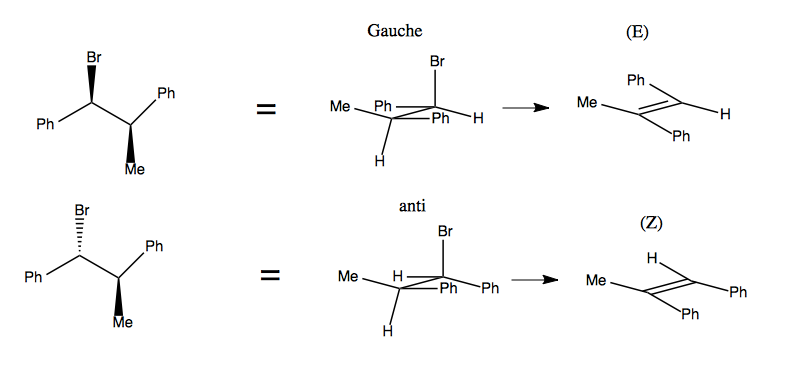

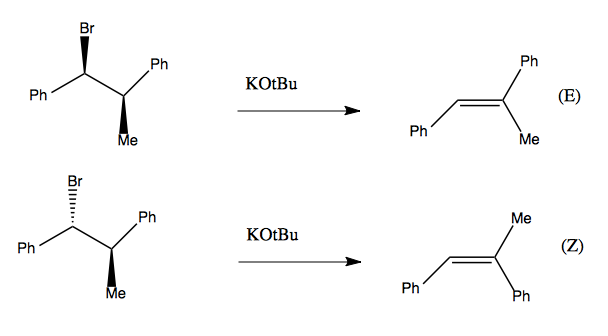

Stereospecific elimination

A stereospecific reaction is one in which stereochemistry in the reactant specifies stereochemistry in the product. Here is an example where having the Br and Me be Gauche vs. anti specifies that you get an (E) or (Z) product, respectively:

This can be understood, again, by looking at diamond lattice structures (or Newman projections):