Organic chemistry 17: Anchimeric assistance, epoxide transformations

These are my notes from lecture 17 of Harvard’s Chemistry 20: Organic Chemistry course, delivered by Dr. Ryan Spoering on March 11, 2015.

Intramolecular reactions

Nucleophilic catalysis

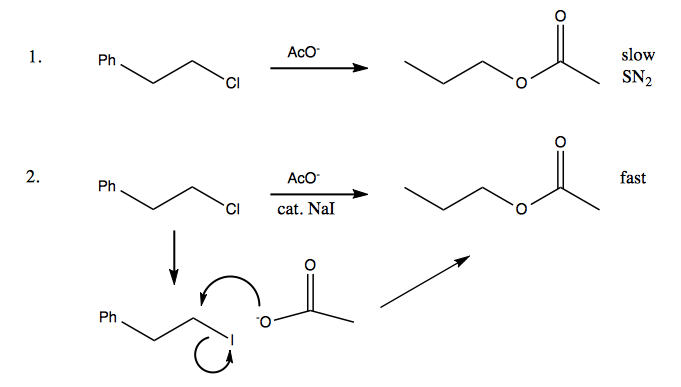

Consider the reaction below. AcO- is a pretty marginal nucleophile (it’s the conjugate base of an acid with pKa = 5), so the top reaction could proceed by SN2 very slowly. Adding “just a pinch” of NaI, however, allows I- to act as a catalyst. The I- initiates a nucleophilic attack on the carbon to which the Cl is bound, thus replacing it. The I is then much more vulnerable to replacement by the acetyl group.

In essence, the iodine lowers the activation energy.

Anchimeric assistance

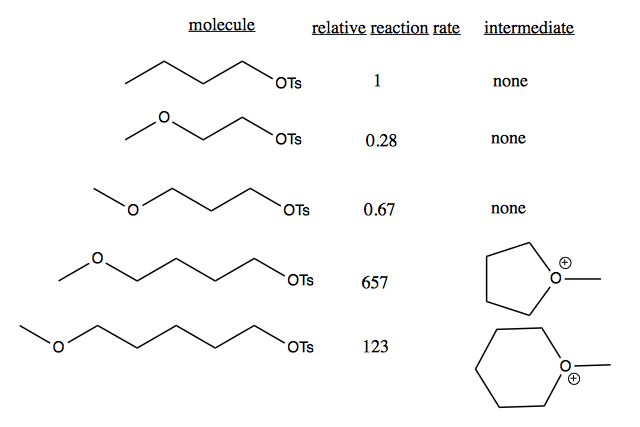

Similar phenomena as above can occur on an intramolecular level. Anchimeric assistance is when a neighboring group participates in a reaction. Consider the following reaction rate data for these molecules reacting with AcO-.

Molecules 2 and 3 are slower than 1 because of an electron withdrawing effect. Molecules 4 and 5 are much faster because the chain is long enough to allow anchimeric assistance, where the molecule can circularize. 7-, 8- or 9-membered rings are also possible, but less favorable than the 6-membered ring.

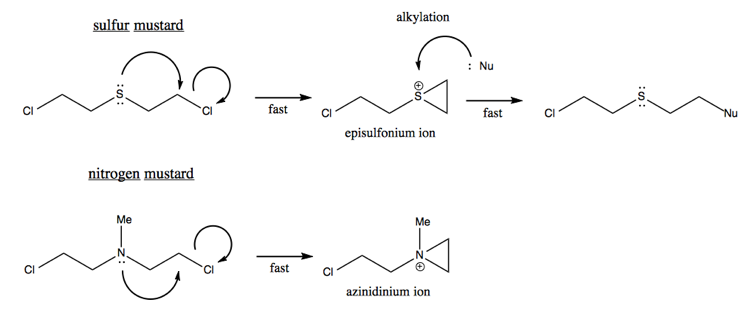

Mustards are a class of powerful aklylating agents, such as mustard gas. These destroy tissue by alkylating everything.

In general, alkylating agents are bad for you - they react with all the weak nucleophiles floating around your cells. While mustard gas is an extreme example, other alkylating agents cause DNA damage and are associated with cancer.

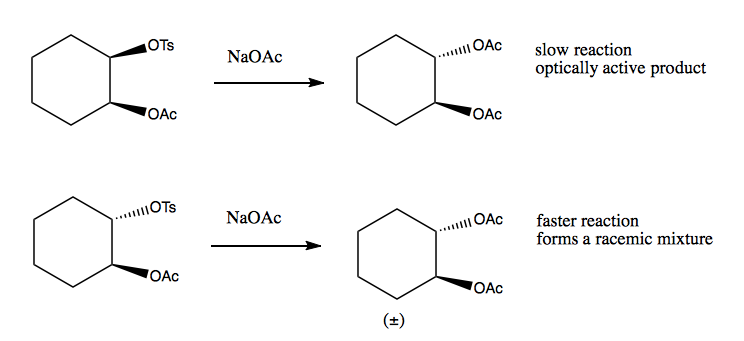

Another example of anchimeric assistance is the reason why the second of these two reactions is faster, and creates a racemic mixture:

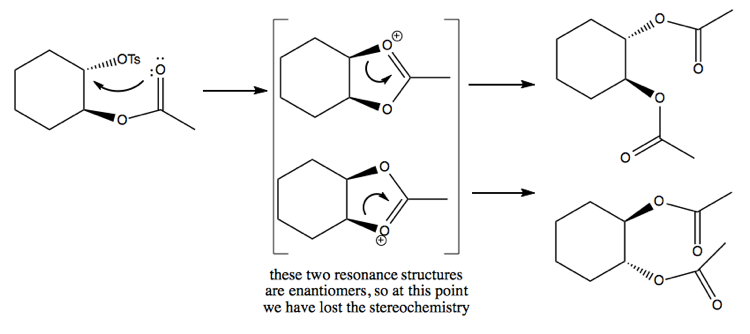

The mechanism for the second reaction involves an intermediate that has a resonance structure, thus losing the stereochemistry of the reactant:

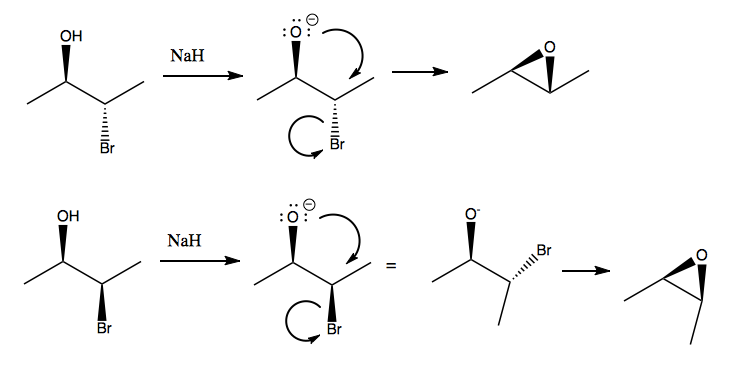

Epoxide synthesis

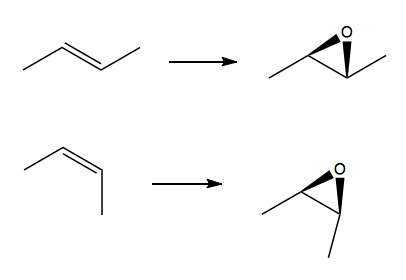

This is actually a poor way to make epoxides, because the synthesis of the original molecule is not easy. The better way to make epoxides is to start from an alkene, and drop the oxygen onto the face of the π bond. The two epoxides being made above could be made from trans and cis butene respectively.

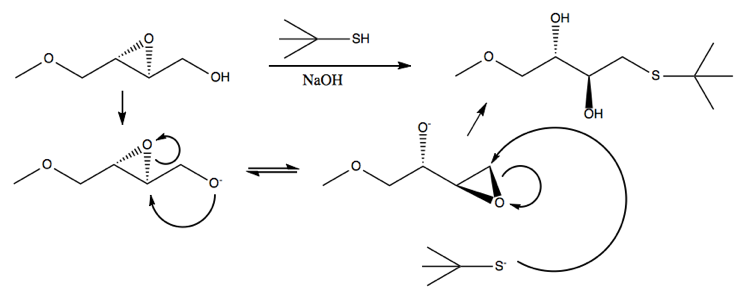

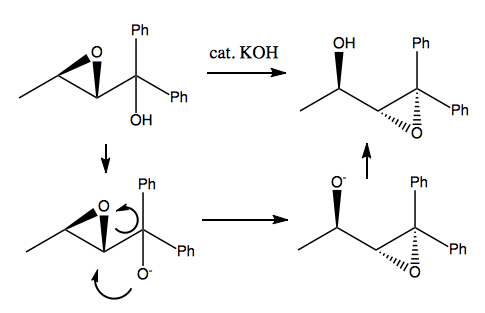

Payne rearrangement

Here is an example:

The more substituted an epoxide is, the more stable it is. This particular reaction is reversible, but the product is somewhat favored over the reactant because the epoxide is triply substituted rather than doubly substituted.

Another example is this reaction, where the sulfur can only attack once the epoxides have rearranged themselves: