Protein folding 08: Chaperones and chaperonin

These are my notes from week 8 of MIT course 7.88j: Protein Folding and Human Disease, held by Dr. Jonathan King on April 2, 2015.

Assignment 7

This week’s reading consists of two papers [Martin 1991, Pereira 2010].

Chaperonin-mediated protein folding at the surface of groEL through a ‘molten globule’-like intermediate

This paper [Martin 1991] discusses the folding state of the intermediates recognized by GroEL/S, a group I chaperonin complex introduced below.

They consider two substrates: chicken dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), which can re-fold and regain activity on its own, and rhodanese, which cannot re-fold and regain activity on its own. GroEL has ATPase activity which is active by default when GroEL is the only protein present. This activity further increases when GroEL contacts a potential substrate such as rhodanese or casein, but decreases when it contacts GroES.

DHFR can re-fold and regain activity on its own, and this activity is actually lost when GroEL (only) is introduced. Adding GroES, Mg2+ and ATP in addition to GroEL allows DHFR to re-fold almost as quickly as it does on its own, though still not quite. In the absence of GroES, increasing concentrations of GroEL slow down DHFR folding (increasing the half-life of folding), while if GroES is present, then the half-life becomes independent of GroEL concentration within the range studied.

In contrast to DHFR, if left to its own devices rhodanese will form aggregates. Aggregate formation is inhibited by GroEL in a perfectly stoichiometric fashion, meaning if you introduce GroEL in a .25:1 ratio, you reduce aggregation by 25%, and if you add it in a 1:1 ratio you completely abolish aggregation. Still, with GroEL alone, although you can abolish aggregation you cannot recover enzymatic activity. Only when you add GroEL, GroES, Mg2+ and ATP do you finally get a nearly full recovery of native activity.

They then ask low-resolution questions about the structure of DHFR and rhodanese bound to GroEL. They begin by measuring tryptophan fluorescence (it helps that GroEL doesn’t contain tryptophan, so you are measuring only the substrate). For both DHFR and rhodanese, the native state has a peak at ~332 nm, and the fully denatured state at ~355 nm, while the state bound to GroEL has a peak at ~343 nm. This suggests that the bound state is a partially folded intermediate. This intermediate state exhibits a strong interaction with ANS. ANS is a small molecule that binds apolar sites on proteins and then fluoresces only if surrounded by hydrophobic residues. The fact that ANS signal is strong in the intermediate is taken to suggest that the intermediate is a “molten globule”, in contrast to the fully unfolded state (where ANS does not get surrounded) or the fully folded state (where complete space-filling excludes ANS from the hydrophobic core).

Crystal Structures of a Group II Chaperonin Reveal the Open and Closed States Associated with the Protein Folding Cycle

This paper [Pereira 2010] reports crystal structures of two different states (open and closed) of a group II chaperonin from archaea.

The canonical Group I chaperonin is the complex of GroEL and GroES. GroEL has equatorial, intermediate and apical domains, where the apical is nearest the GroES cap. Group II chaperonins do not have two distinct subunits - they are simply composed of two octameric rings (thus a 16-mer in total), where, like GroEL, each subunit has equatorial, intermediate and apical domains.

They obtained crystals of the closed wild-type chaperone (Cpn-WT) and open and closed forms of a mutant lacking the lid domain (Cpn-Δlid). Apparently they couldn’t obtain a crystal of open wild-type Cpn.

They present a variety of summary statistics on their structures - numbers which mean nothing to a non-crystallographer - along with cartoons, space-filling models and electron density maps. There is conserved P-loop ATP-binding site with the canonical GDGTTT sequence. There are videos showing the transition between open and closed states - in the closed state, the apical domains lean in towards one another across the ring. In these experiments, there is no substrate present, but presumably in the cellular environment it is the substrate that triggers this change from open to closed conformation. When it closes, the height of the cylinder reduces, and the volume of the cavity reduces from 350,000Å2 when open to 130,000Å2 when closed. The interface between the subunits includes a salt bridge (R425 to D451) present in both closed and open states and thought to be a pivotal part of the contact. In the open state, only the equatorial domains contact one another. The apical domain contains a hydrophobic patch, particularly at the interface between helices 10 and 11, which may stabilize the closed conformation. The inside of the cavity is hydrophilic, with loads of D, E, K and R side chains sticking into it.

The authors speculate that the D, E, K and R help to recognize the substrate. But chaperonins specifically recognize partially folded intermediates, which should have lots of exposed hydrophobic patches, and would hate to be surrounded by D, E, R and K. I wondered if these instead serve to recognize the native state, thus telling the chaperonin when the protein is done folding and can be released - but Dr. King says that what is released from these chaperonins is usually still not the native state, but rather another intermediate that is only somewhat more folded than what went in.

The eukaryotic ortholog of the chaperonin discussed in this paper was discovered in the study of mammalian actin and tubulin. Early efforts to isolate newly synthesized actin found that it was always found in a megadalton-sized complex, which turned out to be this chaperonin. In vitro experiments have shown that this chaperonin can fold actin in about 25 minutes. If you think about scaling this to the amount of actin that a cell uses, you quickly encounter a problem. Actin is one of the most highly expressed proteinsin the cell, and if you do the calculatons on how many copies of this huge chaperonin would be needed to fold all of that actin if each one takes 25 minutes, you get an implausible number. We still don’t know how to resolve this discrepancy - one hypothesis is that the chaperonins just work much, much faster in vivo, folding actin a couple of seconds instead of 25 minutes. We also don’t know how substrates get into chaperonin cavities - again, the mathematics of it would argue there must be active transport and not just diffusion.

Note that these chaperonins are ATP-dependent. They appear to bind substrate independent of ATP but require ATP hydrolysis in order to release the substrate when finished.

The best-characterized substrate of group II chaperonins is VHL. The chaperonin binding site on VHL, identified by making a series of mutations in VHL, turns out to be a series of hydrophobic beta sheets.

Lecture notes

Intro to chaperones and chaperonins

Over the years, the set of functions ascribed to chaperones and chaperonins has increased steadily, in approximately the following order:

- Assisting (but not being essential for) newly synthesized polypeptide chains to reach the native state, in bacteria, and in the cytoplasm, chloroplasts/mitochondria, and endoplasmic reticulum of eukaryotes.

- Being essential for folding of some newly synthesized polypeptide chains.

- Mediating the association or dissociation of subunits of complexes or oligomers.

- Generating a precursor essential for polymerization - for instance for actin or tubulin.

- Stabilizing polypeptides in an unfolded state, for instance to feed them into the proteasome.

- Recognizing misfolded proteins and moving them onto the degradation pathway, possibly in a different subcellular compartment.

- Dissociating aggregated proteins.

Discovery of chaperones

The discovery of chaperones was achieved, largely independently, by three different routes.

One line of inquiry involved rubisco, which is the most abundant protein in plants, which (because plants have greater biomass than other kingdoms) makes it the most abundant protein on earth. Rubisco stands for ribulose bisphosphate decarboxylase. It captures CO2 from the atmosphere. Mature rubisco is an octamer of four copies of each of of two subunits, one large and one small. The newly synthesized large subunit is always found associated with another protein not found in mature rubisco, originally referred to simply as “binding protein” or “large subunit binding protein (L/BP)”.

A second line of inquiry involved the assembly of bacteriophages, often using T4 or λ as model viruses. It was discovered that T4 assembly requires two host proteins expressed by E. coli, which came to be known as GroEL and GroES. (The E in the name comes from the fact that the major coat protein of bacteriophage λ is called E protein). When the amino acid sequence of GroEL was determined, it was found to be homologous to L/BP.

The third line of inquiry concerned animal heat shock genes, studied chiefly in Drosophila. In Drosophila salivary glands, DNA is replicated before it is separated, and the chromatin assembles into giant polytene chromosomes. These polytene chromosomes were often studied because they are visible with relatively low-powered microscopes. They also have another useful property, which is that the chromatin has to open up to allow transcription of RNA, resulting in visible changes in chromatin conformation. You could therefore expose the flies to heat shock, and then look at the chromosomes to see which cytogenic bands had changed conformation in response to the heat shock, implying that genes there had been transcribed. Decades later, after SDS-PAGE was invented, the same questions were asked by pulse-chasing the flies with radiolabeled amino acids (say, containing 14C) and then running proteins on a gel to identify bands that appeared selectively in the presence of heat shock. Such efforts led to the discovery of a series of so-called heat shock proteins, named for their molecular weights (?). The Hsp60s turned out to include a homologue of GroE. Hsp70s included homologues of RNAK, Hsp80s included homologues of DNAJ, Hsp100s included homlogues of Clp, A and X (?), and there was also JHSP20-26 which was a homlogue of α-crystallin.

Elucidation of how chaperones worked

Two key experiments revealed how these newly discovered chaperones worked. A key player in this field was George Lorimer at DuPont Central Research. Rubisco, for all its importance and all its ancientness, is surprisingly slow at its job. In hindsight, the fact that evolution didn’t come up with anything better in 5 billion years might suggest that it can’t be done. Nonetheless, Lorimer’s goal was to engineer a better rubisco, starting with a prokaryotic rubisco from Rhodospirillum rubrum. His group cloned the Rhodospirillum rubisco gene and put it into E. coli but found that it had relatively little activity. They then overexpressed GroE in these E. coli, and found that it increased their yield of rubisco activity.

Rubisco can be denatured by acid, urea, GdnHCl, or heat. There is an important difference between these methods. Whereas GdnHCl yields something that we believe is close to a random coil, an acidic environment results in strong preferences for certain residues to be buried and others exposed. Lorimer’s group denatured rubisco using these different methods, and measured the resulting folds with circular dichroism. They found that urea, acid, and heat all resulted in particular folds with distinctive CD spectra. Only GdnHCl gave a truly flat signal on CD, consistent with total unfolded randomness. They therefore proceeded to denature rubisco in GdnHCl at pH 7.6 in the presence of EDTA and 0.1M salts, and then dilute it into buffer at different temperatures. At any reasonable physiological temperature from 25°C to 37°C they observed zero refolding. They then lowered the temperature even further and found that down around 10°C or lower, rubisco could re-fold, but it took 44 hours, which intuitively strikes one as being far, far longer than it must take in vivo.

They then repeated these experiments with some goodies variably added to the buffer: two chaperones called Cpn60 and Cpn10, and Mg2+, K+, and ATP. Without the chaperones, there was no refolding, just as before. But with the chaperones, ions and ATP added, they finally saw almost 100% recovery of activity at 25°C within about 30 minutes, which might plausibly be the time scale for folding in vivo. They then varied the concentration of Cpn60 and Cpn10 relative to rubisco. Surprisingly, the relative yield was maximized when these three were present in a 1:1 molar ratio. Excess chaperone reduced the yield, and excess rubisco did not add to the yield.

They then asked whether the order of events was important. They diluted rubisco out of denaturant into buffer without chaperones, and then added the chaperones post-hoc. This revealed that the ability to recover rubisco activity depends on the time elapsed between dilution into naked buffer, and the introduction of chaperones. You can recover activity if you add chaperones right away, but not if you wait a half hour. The conclusion was that the substrate for the chaperones is a partially folded intermediate monomer. If the partially unfolded intermediate is left unchaperoned for too long, it aggregates, at which point the chaperones can no longer rescue it. These experiments did not exactly rule out the possibility that the chaperone’s substrate is a fully unfolded polypeptide chain, and indeed, it is difficult to completely disprove this. However, some experiments have been done with cytochrome c, which denatures at 0.8M GdnHCl, a concentration at which GroE remains fully folded, which indicate that GroE does not interact with fully denatured / fully unfolded polypeptides.

The idea of a partially folded intermediate as substrate led to a question of exactly what structure the chaperones were recognizing in that intermediate. This remains somewhat mysterious, but we at least got some answers when the structure of GroE was solved [Xu 1997, PDB# 1AON].

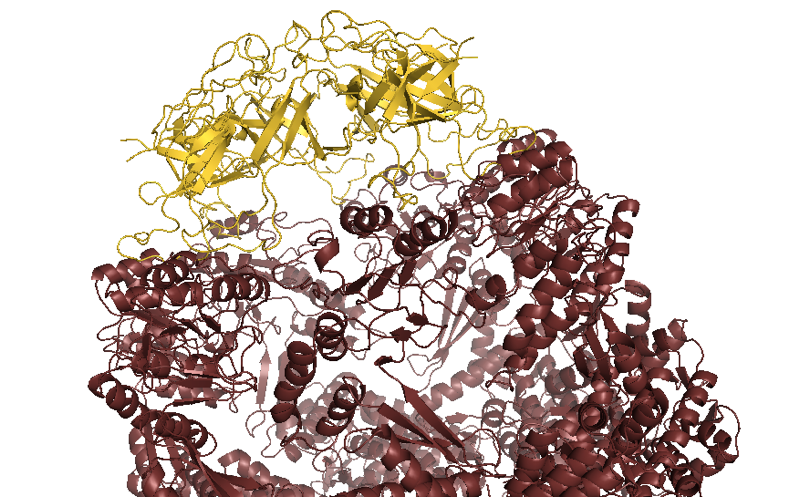

fetch 1aon

bg_color white

hide everything

show cartoon

color 0x802A2A

color 0xFCD116, chain O or chain P or chain Q or chain R or chain S or chain T or chain U

Above: GroEL (maroon) capped by GroES (yellow).

GroE is a double barrel where each half composed of seven copies of the large subunit (GroEL) with a cap composed of seven copies of the small subunit (GroES). It seems that the cap opens, allows an unfolded protein in, some mysterious folding events happen inside the closed barrel, and then the cap opens again. How this all actually works remains mysterious. Experimental evidence indicates that the two chambers of the double barrel operate independently, but this makes no sense conceptually, because then why would it have evolved as a double barrel.