Organic chemistry 24: Alkynes - reactions, synthesis and protecting groups

These are my notes from lecture 24 of Harvard’s Chemistry 20: Organic Chemistry course, delivered by Dr. Ryan Spoering on April 6, 2015.

Introduction to protecting groups

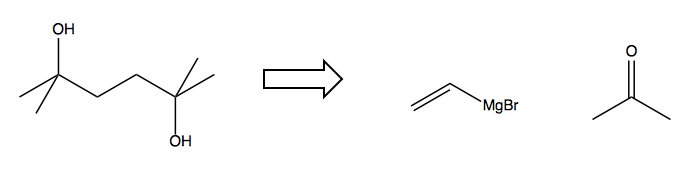

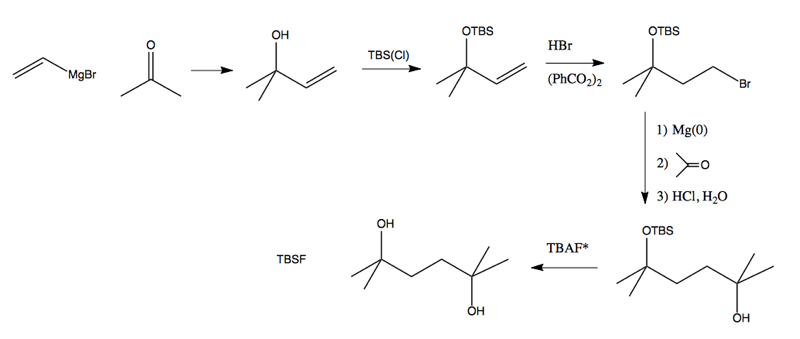

Consider this retrosynthesis problem. The block arrow means “figure out how to make the thing on the left from the things on the right”.

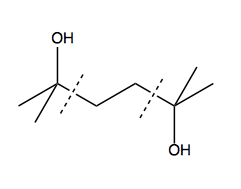

We can quickly recognize two tertiary alcohols connected by an alkane:

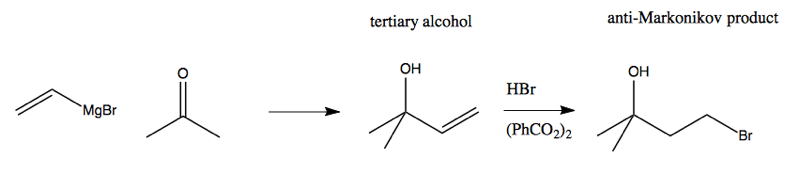

And based on that thinking, we can devise this beginning to our synthesis strategy:

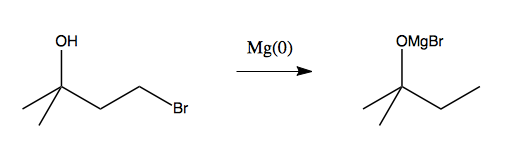

However, at this stage we are stuck. We want to use a Grignard reagent next, but if we do, it will attack the alcohol:

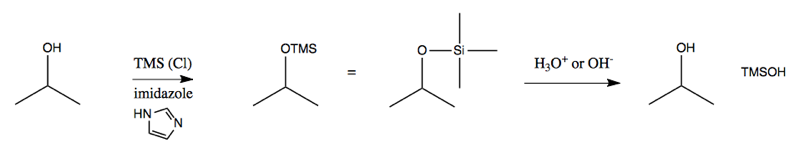

This motivates the need for a protecting group. We need a way to block the alcohol from reacting while we do something else, and then freeing it up again. The canonical protecting group is some sort of silyl ether. The simplest way to achieve this is with as trimethylsilyl (TMS; Me3Si):

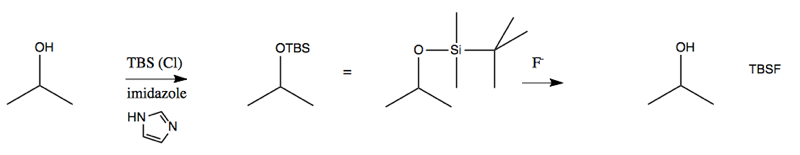

In other words, TMS will form an ether with your alcohol, and can be removed again upon addition of acid or base. However, this group falls off so easily that it’s actually not as useful as it could be, and therefore is not that often used. A more useful reagent is tBuMe2Si, abbreviated TBS. Amazingly, just substituting different alkanes on the silicon makes a big difference in how easy the group is to remove. TBS is removed most readily by F-.

With TBS in our toolkit, we are now ready to solve the retrosynthesis problem at top:

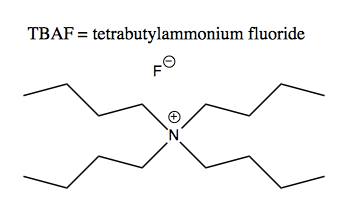

The TBAF is a source of fluoride; its structure is this:

Alkynes in synthesis

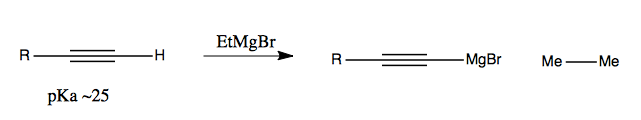

Alkynes can be used together with Grignard reagents:

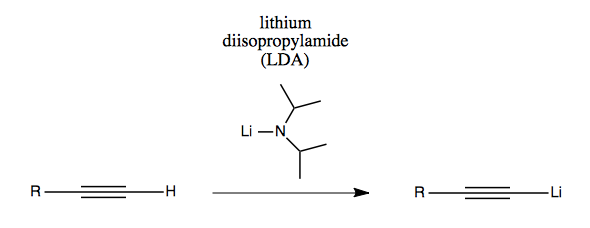

Another option is the bulky base lithium diisopropylamide (LDA).

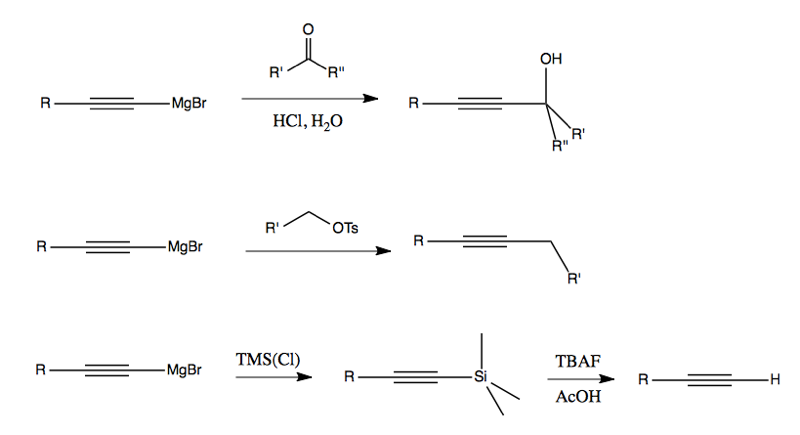

Alkynyl Grignards are unique among Grignards for their ability to do SN2 chemistry. (All other Grignards are too basic / too reactive, and may just give you an E2 product). Once you have your alkynyl Grignard or alkynyl lithium reagent (above), you can react with (for example) carbonyls, OTs, or TMS:

Reduction of alkynes

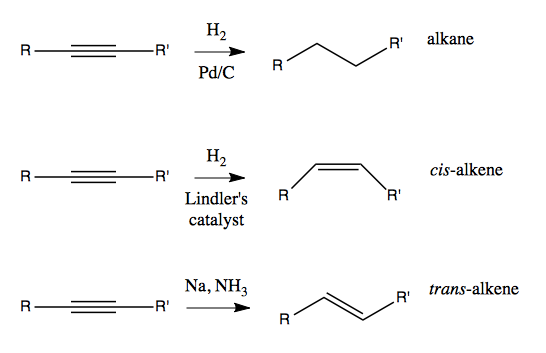

An alkyne can be reduced (hydrogenated) to an alkane using Pd/C, or reduced only to an alkene using Lindler’s catalyst (cis) or Na and NH3 (trans). This means that if our end goal is an alkane or alkene, we have the option of doing our chemistry with an alkyne and then reducing it later.

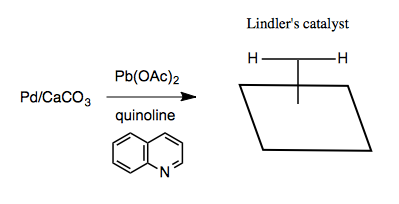

How do these reduction reactions work? Lindler’s catalyst is said to be a poisoned catalyst. Similar to Pd/C, you end up with a metal surface with hydrogens projecting up out of it, ready to react with an exposed face of alkynes.

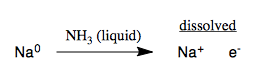

The Na, NH3 reaction is referred to as dissolving metal reduction. The Na metal actually dissolves in the ammonia, producing a beautiful deep blue solution:

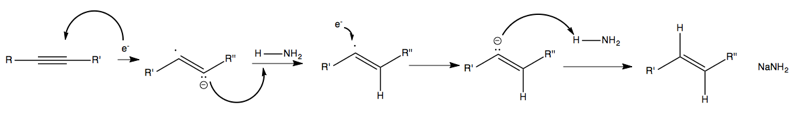

The electron that dissociates from sodium then attacks the triple bond, yielding a radical anion which reacts with ammonia twice to add two hydrogens:

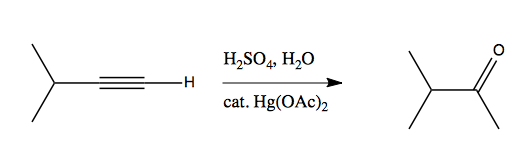

Hydration of alkynes can also be achieved using sulfuric acid and mercury acetate:

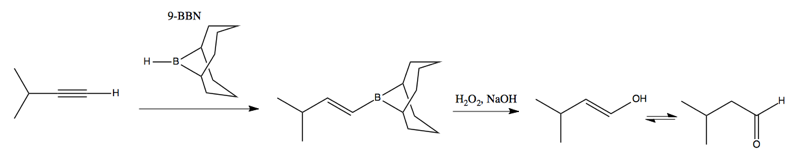

You can also perform hydroboration of alkynes using 9-BBN, introduced in lecture 20:

Another retrosynthesis problem

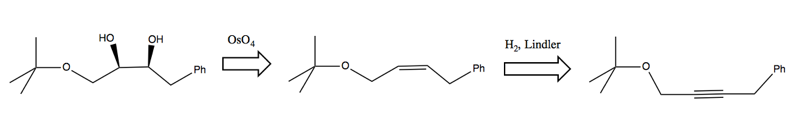

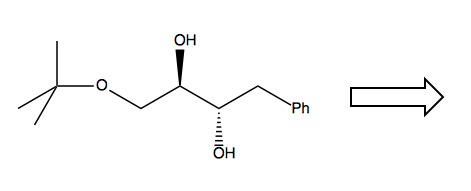

Now consider this problem:

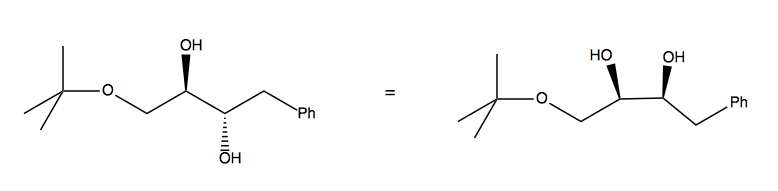

Right away, we must recognize that we’ll need to take special care to create the stereochemical relationship between the two hydroxides. Observe that the bond in between the two -OH can rotate. Therefore we can think of this as either a trans anti configuration, or a cis syn configuration:

Once we recognize this, it becomes possible to design a synthesis by reducing an alkyne with Lindler’s catalyst and then adding the hydroxyl groups with OsO4: