Organic chemistry 27: Introduction to aromaticity

These are my notes from lecture 27 of Harvard’s Chemistry 20: Organic Chemistry course, delivered by Dr. Ryan Spoering on April 15, 2015.

Aromaticity

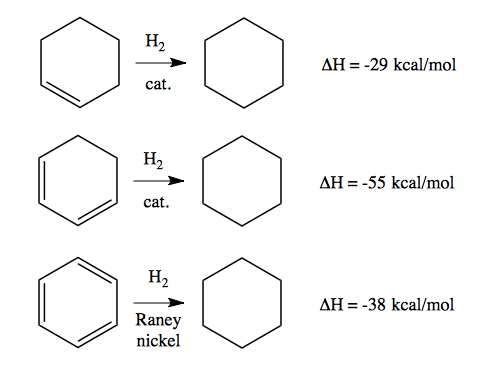

Aromaticity is conjugation, but it is a very special kind of conjugation that confers an unexpectedly large amount of stability. Consider the following reductions:

All are downhill, with a negative change in enthalpy. The ΔH from hydrogenating away one double bond is -29 kcal/mol, but for two double bonds it is -55 kcal/mol rather than -58. This indicates that the two-double-bond cyclic compound at middle left has a 3 kcal/mol stabilization due to conjugation of the two π systems. Then even more surprisingly, the ΔH for hydrogenating away all three π bonds in a benzene is only -49 kcal/mol. -29*3–49 = -38, meaning that benzene has 38 kcal/mol of stabilization due to conjugation.

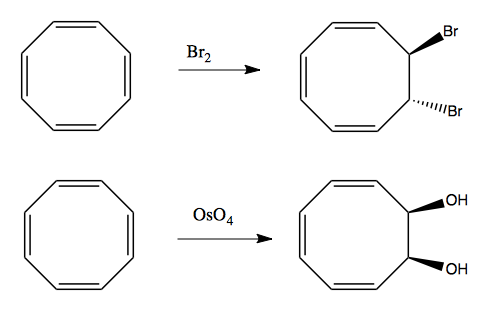

Benzene is unique in this regard. Consider for contrast cyclooctatetraene:

Cyclooctatetraene isn’t even flat - it has a “tub conformation”:

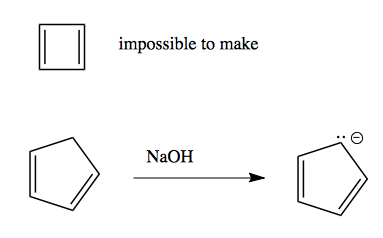

So in effect, the four π systems are as independent as if this was just a linear alkene. In addition, other cyclic alkenes have unexpected properties too: cyclic butadiene cannot be isolated at all. Cyclic pentadiene is surprisingly stable and able to donate a proton - in fact, it has a pKa of just 15:

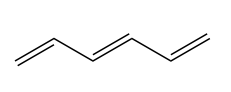

To understand all of these phenomena, which cannot be readily explained in light of what we’ve learned so far in this class, we must turn to frontier molecular orbital theory. Consider an FMO analysis of a linear hexene with three double bonds:

Here are its orbitals in descending order of energy:

| orbital | occupied | orientation | nodes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ψ6 | __ | + - + - + - |

5 |

| Ψ5 | __ | + - + + - + |

4 |

| Ψ4 | __ | + - - + + - |

3 |

| Ψ3 | ↑↓ | + + - - + + |

2 |

| Ψ2 | ↑↓ | + + + - - - |

1 |

| Ψ1 | ↑↓ | + + + + + + |

0 |

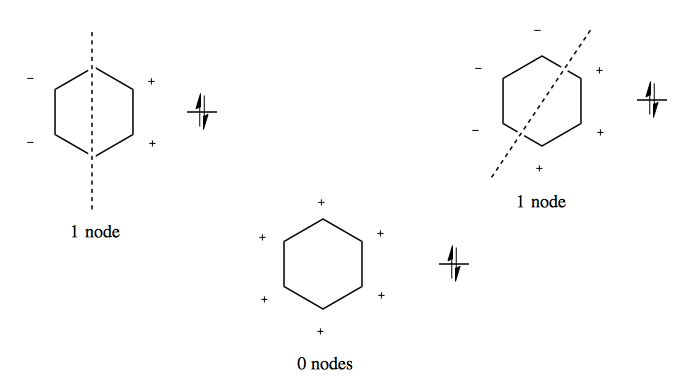

Benzene is different than that. Because it is cyclic, there are two different orientations that each result in exactly 1 node. Thus, these two have equivalent energy, and are called degenerate. These orientations result from bisecting the molecule through two atoms or through two bonds:

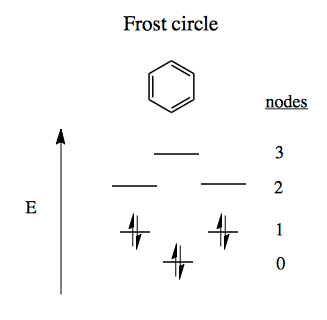

Similarly, there are two ways to introduce exactly two nodes into this molecule, and one way to introduce 3 nodes. Thus we can have six different orbitals without ever having more than 3 nodes, which gives benzene extremely low energy. The FMO diagram for benzene thus looks like a Frost circle.

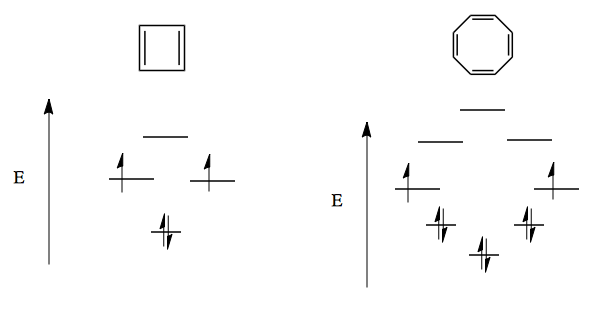

This way of thinking also leads to anti-aromatic configurations which explain why cyclobutadiene cannot exist, and why cyclooctatetraene forces itself out of planar configuration in order to avoid an unfavorable state:

These observations lead us to Hückel’s Rules: to be aromatic, a compound must be:

- Cyclic, with a continuous array of p-orbitals (π systems)

- Planar, so there is orbital overlap

- Contain 4n+2 π electrons

Rule #3 gives us 6, 10, 14… as possible numbers of electrons.

Compounds that meet all three rules are aromatic. Compounds that meet rules 1 and 2 but not 3 are anti-aromatic. Compounds that fail to meet either rule 1 or rule 2 are simply non-aromatic.

| rule | benzene | cyclobutadiene | cyclooctatetraene |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. cyclic | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 2. planar | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| 3. 4n+2 | ✓ (6) | ✗ (4) | ✗ (8) |

| diagnosis | aromatic | anti-aromatic | non-aromatic |

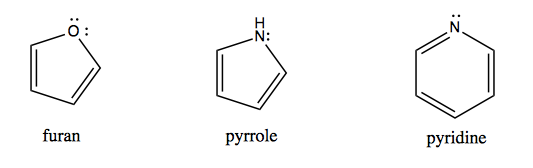

Then there are heteroaromatic compounds in which a heteroatom becomes part of an aromatic system. The following three compounds have very different reactivity:

In pyrrole, the nitrogen lone pair is part of the conjugated π system so it is very non-reactive. In pyridine, the nitrogen lone pair is “extra”, hanging off the end of the ring, so it is highly reactive.

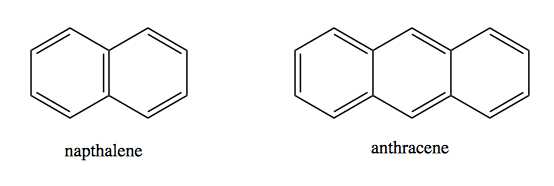

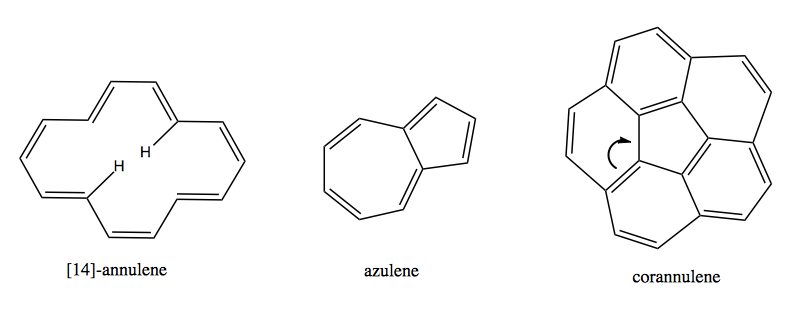

Then there are polycyclic compounds which are multiple ring systems stuck together:

Polycyclics can get very large indeed. Graphite is simply sheets of benzene rings stuck together. Bucky balls are another example. As you get larger and larger polycyclics, the 4n+2 requirement eventually relaxes.

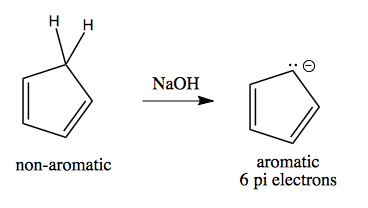

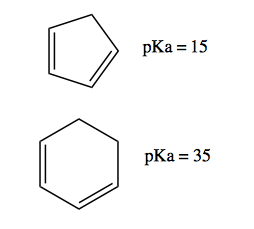

Aromaticity allows us to understand the reactivity of cyclopentadiene, introduced above. It is non-aromatic when protonated, but by deprotonating it can become aromatic:

Thus, it has a pKa of 15, compared to 35 for the corresponding cyclohexadiene, which is not aromatic when de-protonated:

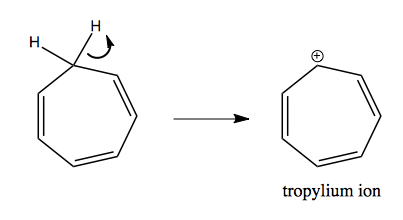

This also explains the propensity of cycloheptatriene to lose a hydrogen, becoming a tropylium ion:

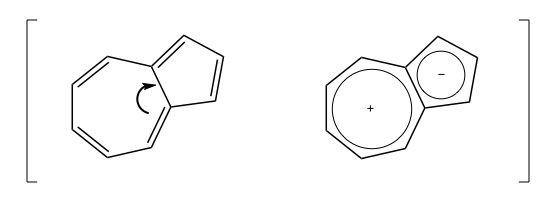

There are even stranger combinations:

Azulene has a resonance structure where electrons move from the 7-membered ring into the 5-membered ring so that each has 6 electrons, thus giving the compound a dipole moment and giving it a bright blue color: