Chemical biology 08: The role of natural products in drug development

These are my notes from lecture 8 of Harvard’s Chemistry 101: Chemical Biology Towards Precision Medicine course, taught by Dr. Stuart Schreiber on October 1, 2015.

Introduction

This and the next lecture will discuss two major challenges in organic synthesis: targeted syntheses (today) and diversity syntheses (next lecture). Targeted synthesis is trying to make a molecule with a known structure. While natural products are exquisitely evolved to have good pharmacodynamics (how a drug affects its target / the body), they are not under much selection for good pharmacokinetics (how the human body processes the drug), so often one needs to figure out how to synthesize a natural product in order to begin tweaking it in search of better pharmacokinetic properties.

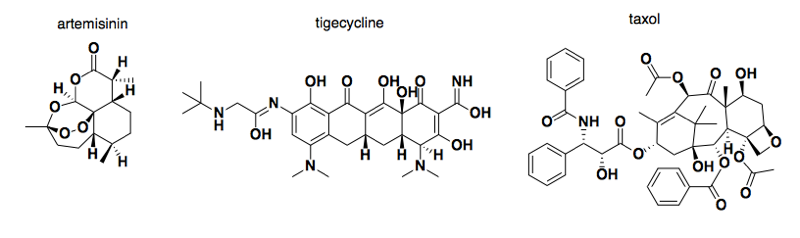

Above: some examples of natural products that became drugs: artermisinin (青蒿素), tigecycline, and taxol.

The halichondrin story

Overview:

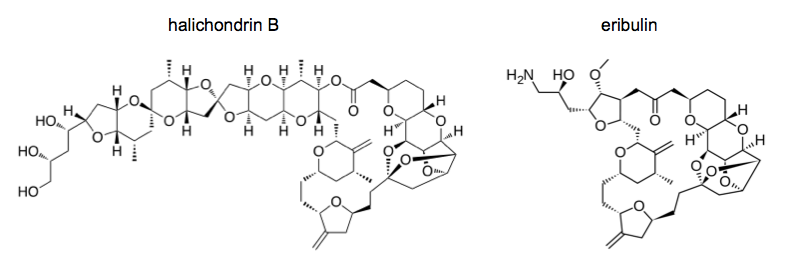

- Halichondrin is a structrually complex natural product

- Halichondrin synthesis was achieved in the Kishi laboratory

- The Kishi lab and Eisai performed SAR on the synthesis and developed eribulin, which got approved for metastatic breast cancer

- Halichondrin and eribulin are “antimitotic” chemotherapy drugs, as distinct from targeted cancer therapies. Modern cell biology is trying to identify new targets in antimitotic drug development.

Halichondrin refers to a series of structurally similar natural products (norhalichondrin A, halichondrin B, etc.) produced by the sea sponge Halichondria okadai. This sea sponge was originally better known for producing the phosphatase inhibitor okadaic acid. Okadaic acid is incredibly toxic and is present in the sponge in vast excess to halichondrin, plus the sea sponges are physically difficult to collect from the sea floor using submersibles. Therefore, these sponges were a bad way to get halichondrin.

Synthesis of halichondrin required asymmetric synthesis, which means reactions that proceed with enantiotopic or diastereotopic group or face selectivity in unequal amounts. Note that “unequal amounts” is a qualitative, not quantitative, designation, so even a 51%/49% synthesis is still asymmetric.

In this sort of approach, modular synthesis is incredibly important. In other words, you need to synthesize the product in multiple parallel steps that converge at the end. If you have a single linear series of steps, then it will be very difficult to tweak it to get any even slightly different product. A great challenge of modular synthesis, however, is that each intermediate product you make is precious, because you’ve already put many steps into it. Therefore you don’t have one cheap reagent that you can add in great excess to drive the reaction. Very rarely in synthesis is it possible to get an efficient reaction by adding two reactants in a 1:1 ratio. Crucial to Kishi’s synthesis of halichondrin was the discovery of a means for coupling two of the reactants of interest in equal amounts. This required a Nozaki-Hiyama-Kishi reaction. This reaction was originally a chromium coupling reaction; Kishi’s contribution was the realization that trace amounts of nickel greatly increased the reproducibility of the reaction.

Once Kishi had synthesized halichondrin B, they partnered with Eisai and began structure-activity relationship studies. The right half of halichondrin B possessed almost all of the whole compound’s activity in cell culture, but lacked any in vivo activity in mice. In cell culture, the mitotic block was reversed after drug washout. They started to search for compounds that would retain activity after washout. To identify the target, they biotinylated the molecule, used it to pull down proteins, then ran the proteins on a gel. On the hypothesis that the target might be tubulin, they blotted with antibodies against alpha and beta tubulin, and sure enough, both of these tubulins were being pulled down by the molecule.

They performed medicinal chemistry on over ten different atoms and groups in the molecule, achieving various improvements in solubility and resistance to degradation in vivo. This was pioneering work; before this, no one believed that you could do medicinal chemistry on such a complicated molecule. Eventually they arrived at the molecule now known as eribulin, which received FDA approval in 2010. When the FDA approves a drug, they are not only regulating the end product, but also all of the intermediate steps, certifying that all of the intermediates are of sufficient purity and that the nickel and chromium and other catalysts have been removed. The eribulin synthesis approved by FDA required 62 steps. The Kishi lab has since developed a vastly improved, more efficient synthetic pathway for eribulin, but the new pathway is not FDA-approved, so all eribulin used clinically has to be synthesized the old way.

Eribulin is but one of many chemotherapeutic agents that target tubulin. There are many structurally distinct natural products that bind tubulin, in part because it is an essential protein and therefore a desirable target, but also because it is easy to find compounds that bind tubulin. If you do a screen of a compound library, a lot of pretty simple synthetic compounds — much simpler than taxol or eribulin — have similar effects on tubulin. All tubulin-targeting agents are neurotoxic and often result in severe neuropathic pain because they disrupt the microtubules that are essential for long-distance trafficking of neurotransmitters in peripheral nerves. This inspired the development of “clean” antimitotics whose targets — aurora kinase, kinesin-5 — are not expressed in neurons. Frustratingly, though these drugs successfully avoided neurotoxicity, they also proved far less effective than anti-tubulin drugs. This has led to speculation that the anti-cancer effects of anti-tubulin drugs are not mediated solely by interferene with mitosis, and may instead involve mitochondria or other targets as well.

In targeted therapies, cancers will often develop resistance through mutations in the target. In chemotherapy, that’s not possible because tubulin is too essential; instead, tumors sometimes become taxol-resistant through upregulation of efflux proteins that expel taxol from the cell.