Biochemistry 05: carbohydrates, glycoproteins and lipids

These are notes from lecture 5 of Harvard Extension’s biochemistry class.

carbohydrates

Monosaccharides are a single linear chain or cyclic ring. These come in two families. Aldose (e.g. glyceraldehyde) has an aldehyde as its carbonyl gruop. Ketose (e.g. dihydroxyacetone) has a ketone as its carbonyl group. Sugars can also be named by the number of carbons (e.g. pentose). But no matter what, the C:H:O ratio is 1:2:1. Most monosaccharides are chiral. Suppose you write the CHO on top, CH2OH at bottom. Then if HO is left and H is right, that’s L and if H is left and OH is right that’s D. Most natural sugars are D:

CHO | H-C-OH | CH2OH

The reference carbon for naming chirality is the chiral carbon most distant from the carbonyl (C=O, top in above diagram) end.

Epimers are sugars that differ only in the configuration around one carbon atom. Example from Wikipedia:

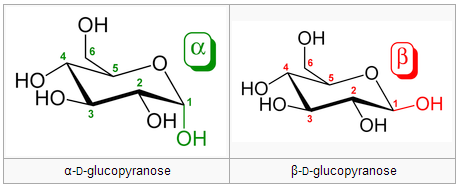

Anomers differ in configuration around the hemiacetal carbon. Anomers can freely convert between the alpha and beta forms. A free anomeric carbon can act as a reducing agent, thus making the sugar a “reducing sugar.” Example from Wikipedia (the bottom row are anomers of the two epimers above):

Oligosaccharides are chains of 2-10 monosaccharides. Disaccharides are most abundant, e.g. sucrose = glucose + fructose. Disaccharides are formed via a hydrolysis and condensation reaction that forms a glycosidic bond. If the first molecule is in a beta configuration and its 1st carbon is linked to the other molecule’s second carbon, it’s called a β1-4 bond. Re: the above paragraph, a carbon is not “free” if it is involved in a glycosidic bond, and therefore cannot act as a reducing agent.

Polysaccharides can be thousands of units.

Homopolysaccharides have only one type of unit; heteropolysaccharides have multiple. Either can be straight or branched. Glycogen, starch and cellulose are homopolysaccharides. Heteropolysaccharides are found in the extracellular matrix.

Starch is a chain of glucose linked by α1→4 linkages. Amylopectin is a particular configuration of branched starch with just one available reducing end, because all other would-be reducing ends are taken up by branching. If interfolded with amylose it can create a starch granule. When amylopectin is degraded, glucose is taken off the non-reducing end.

Glycogen is the fuel storage molecule in animals. Like amylopectin it is glucose in α1→4 linkages, but it branches approximately once per 10 glucose molecules. Glucose is removed from the non-reducing end. Glycogen is abundant in liver and skeletal muscle.

Cellulose is a β1→4 polymer of glucose. The bonding structure provides rigidity and strength – cellulose forms the hard structure in plants. We do not have enzymes that can break down β1→4 linkages, which is why we can’t digest cellulose. (Nor do ruminant genomes encode enzymes to break down cellulose – instead they harbor gut bacteria that do it.)

glycoproteins

Glycoproteins are proteins with glycan chains attached. See PrP glycosylation post.

The carbohydrate content of glycoproteins can be < 1% to > 90% of their mass. Most secreted and membrane-associated proteins are glycosylated (latter on the exoplasmic side only). N-linked oligosaccharides are attached to nitrogen in asparagine cotranslationally. O-linked oligosaccharides are attached to oxygen in serine or threonine post-translationally, usually in the Golgi.

Oligosaccharides can assist in chaperone folding, provide “tags” for protein binding, or provide blood type specificity. The chaperone folding thing refers to the calnexin/calreticulin cycle where the number of glucose molecules is a sort of “code” for whether the protein has achieved correct folding.

Carbohydrate-binding proteins called lectins need to see specific oligosaccharide “tags” on substrate proteins in order to act. They then control the rate of degradation for some peptide hormones. Many viruses have lectins on their surface to recognize specific oligosaccharides that are markers of the cells the viruses want to target.

Everyone has fucose on their glycans on blood cells. Blood type A has a branched tip with N-acetylgalactosamine and fucose; B has a branched tip with galactose and fucose; O only has fucose.

Proteoglycans are glycoproteins with very large polysaccharides called glycosaminoglycans (GAGs). GAGs are very large repeating units of disaccharides. GAGs have an acetylamido group and a sulfation group. These enormous fan-like branches maintain the structure and rigidity of the extracellular matrix. Hyaluronate is one such component. It is highly hydrated, i.e. it holds a lot of water. Physical pressure releases this water until the negative charges of the GAG chains themselves resist each other. Thus GAGs can act as a “buffer” against pressure and are important in the resilience of cartilege.

Proteoglycans are not only found free in the extracellular matrix. They also exist in membrane-bound forms.

lipids

Lipids are largely hydrophobic, though some have polar components. They don’t form hydrogen bonds. Fatty acids are a hydrocarbon chain of varying length (most common lengths are C16 and C18) with a carboxylic acid group at one end. Unsaturated fatty acids have one double bond, polyunsaturated have more than one double bond. Conventional fatty acid nomenclature specifies the chain length and the placement of double bonds. For instance, 18:1(Δ9,12) Linoleic Acid tells you that the two double bonds start on carbons 9 and 12. In an alternate, froofier naming scheme, omega tells you how far the double bond is from the last carbon, so Omega-3 fatty acids have a double bond three spots from the end. Cis double bonds occur naturally; trans double bonds are very rare naturally (a little bit in some animal fats) but can of course be produced artificially.

Unsaturation produces kinks which interfere with fatty acid packing. Saturated fatty acids pack tightly with atoms all along their length engaging in van der waals contact with adjacent molecules. Melting temperatures decrease with the degree of unsaturation.

We’ll categorize lipids into storage lipids, which are neutral, and membrane lipids, which are polar.

All lipids have a backbone of either glycerol or sphingosine. The polar membrane lipids also have a polar head group. See plasma membrane.

Triacylglycerol is the storage lipid. It is a glycerol backbone with three fatty acid chains attached via ester linkages.

Glycerophospholipids have a glycerol backbone with fatty acids at positions 1 and 2 but a polar or charged head group attached to position 3 via phosphodiester linkage. The identity of the head group determines which phospholipid it is.

Sphingolipids have a sphingosine backbone. A sphingosine with a fatty acid on the middle amide linkage is called a ceramide. Head group varies and there are phosphoshingoplipids and glycosphingolipids. Sphingomyelin is most common and is a key part of myelin in the CNS. See also cerebrosides and gangliosides.

take home points

- Classifications and what they’re based on

- Different components

- Different backbones

- Recognize and identify the different structures.