Biolit 03: cGAMP

These are my notes for week 03 of Harvard’s BBS 230 “Analysis of the biological literature” course (September 16-18, 2014). This includes my own reading and analysis of the papers, as well as my notes from both discussion sections.

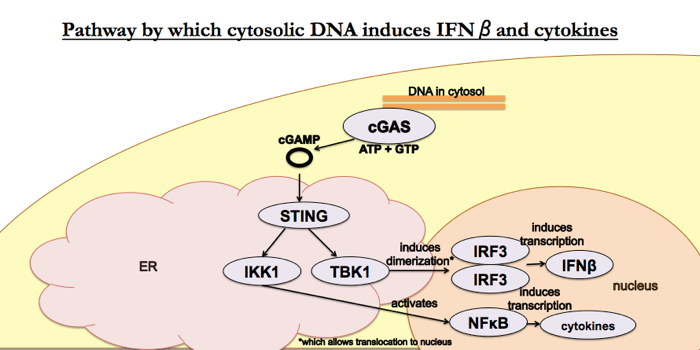

The papers for this week are [Sun 2013] and [Wu 2013], published by the same group — Chen Zhijian (陈志坚)’s group at UT Southwestern Medical Center — in the same issue of Science. Together, the two papers established this pathway:

Wu 2013: Cyclic GMP-AMP is an endogenous second messenger in innate immune signaling by cytosolic DNA

Historical context

Second messengers are a means by which signals can be amplified in cellular signaling pathways. By 2013, already known second messengers included cAMP, IP3, DAG, and Ca2+ - see Cell Biology 09.

Innate immunity is responsible for immediate response to a small set of molecules that are associated with pathogens. It is an ancient system common to most (all?) animals. Activation of the innate immune pathways results in secretion of cytokines which will attract adaptive immune cells to the site and which will also induce macrophages to phagocytose invading bacteria. The 2011 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded in part to Bruce Beutler and Jules Hoffmann for clarifying the role of toll-like receptors in innate immune response to lipopolysaccharide.

Methods

The authors’ assays rely on permeabilizing cells. To permeabilize cells, one might often use a low concentration of a detergent such as Triton. These authors instead use perfringolysin O (PFO) instead, probably because it is a very mild treatment. Whereas detergents will change many things in the cell (protein folding, etc.), PFO is a Clostridium protein exotoxin which specifically forms pores in the cell membrane.

The readout for pathway activation (eventually called the “cGAMP activity assay”) relies on dimerization of a transcription factor called IRF3 (interferon regulatory factor 3). You can’t detect dimerization of proteins in a standard Western blot protocol, because boiling samples in SDS will dissociate the dimers. Instead, they use 35S-labeled IRF3, which they add to the permeabilized cells along with the activated lysates from other cells, and then they run the IRF3 on a native gel. This protocol avoids boiling in SDS, and the use of exogenously added radiolabeled IRF3 ensures that any IRF3 dimers that are detected were formed after addition of the activated lysate (whereas if they’d done a Western blot they would have had to deal with background due to a baseline level of endogenous IRF3 dimerization).

Figure by figure

- Figure 1 uses IRF3 dimerization as a readout for whether the pathway of interest is being activated. They find it can be activated by any just old DNA sequence - herring testis DNA, poly(dA:dT), poly(dG:dC), poly(dI:dC), or interferon-stimulatory DNA all work. No RNA sequence works - for instance, poly(I:C) (the RNA equivalent of dI:dC) or some unspecified ssRNA don’t work. For the DNA sequences which do work, shRNA against STING prevents the IRF3 dimerization. This all works in a number of different cell lines (though not HEK293T cells). The activating messenger is not degraded by heat nor nucleases nor proteases, so it must be a small molecule. So: cytosolic DNA, but not RNA, stimulates IRF3 dimerization via STING via a small molecule messenger.

- 1A. Is simply a diagram of what they did.

- 1B. Shows that IRF3 dimerization requires both DNA-activated cell lysate and permeabilization of the target cells.

- 1C. Shows that the messenger is heat-resistant (left panel vs. right panel) and sequence-independent (ISD vs. HT-DNA lanes). Though not included in the figure, they also performed benzonase and proteinase K digestions to show that the messenger is not a protein or nucleic acid. By elimination, it is probably a small molecule.

- 1D. Shows that the messenger is DNA seqeunce-independent but does require DNA and not RNA. This reaction also required ATP (as mentioned in the legend).

- 1E. The response they’ve been observing is STING-dependent, because shRNA against STING reduces or eliminates the response.

- 1F. IRF3 dimerization can also be induced by other pathways - Sendai virus, which is an ssRNA virus, causes IRF3 dimerization. However, the ssRNA-sensing pathway is not STING-dependent, because shRNA against STING does not affect IRF3 dimerization induced by Sendai virus. Actually, it was already known that this RNA sensing was STING-independent.

- 1G. Surveys a variety of cell lines; HEK cells do not respond to the messenger in question, all the other types do - even MEFs, which are not immune cells.

- In Figure 2 they performed mass spec to identify the small molecule messenger. In reality they may have already had a hypothesis that it would be some sort of cyclic dinucleotide, because they mention elsewhere that c-di-GMP and c-di-AMP were already known to stimulate STING. But in any event, they tagged STING with FLAG, and then performed affinity chromatography to get fractions containing the active molecule, then subjected these fractions to mass spec. The mass spectra identified a peak present only in active fractions, which was halfway between the c-di-GMP and c-di-AMP mass/charge ratios, and this molecule proved to be cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP). They then chemically synthesized it and showed that the synthetic cGAMP gave the same peak in mass spec.

- 2A. Shows mass spectra from the active fraction vs. background, and highlights one peak which is unique to the active fraction. Based on this they were able to hypothesize it was cyclic GMP-AMP. This molecule had been observed in Vibrio cholerae before but was novel in eukaryotes.

- 2B. They then further fragmented their fractions by collision-induced dissociation (CID) - colliding the molecules with inert gases. The peaks they detected corresponded to expected masses of fragments of cGAMP.

- 2C. They perform HPLC on their fractions and show that the presence of cGAMP in HPLC fractions is associated with activity in the IRF3 dimerization assay.

- 2D. They repeat CID on the HPLC-purified cGAMP and synthetic cGAMP and show that the CID spectra are the same.

- In Figure 3 they show that their synthetic cGAMP can activate IFNβ, and they also show that infection by DNA viruses (but not RNA viruses) also causes IRF3 dimerization similar to that seen in Figure 1. As far as I can tell, these two messages (“synthetic cGAMP induces IFNβ” and “DNA virus infection causes IRF3 dimerization”) were combined into one figure just for space.

- 3A. Chemically synthesized cGAMP induces IFNβ over a time course. They measured both RNA (by qPCR) and protein (by ELISA).

- 3B. Chemically synthesized cGAMP induces IFNβ in a dose-dependent manner.

- 3C. Chemically synthesized cGAMP induces IFNβ more than c-di-GMP does. This might be included because previously people had thought that STING’s native function was to detect c-di-GMP which is a bacterial signaling molecule. This suggests that the cGAMP pathway is STING’s primary function, and c-di-GMP sensing may be off-target.

- 3D. A setup for 3E. This just shows that DNA and DNA viruses, but not RNA viruses, are capable of stimuating IRF3 dimerization compared to levels of endogenous IRF3 dimerization.

- 3E. HPLC demonstrates presence of cGAMP in the active but not inactive extracts from Figure 3D.

- 3F. This doesn’t use chemically synthesized cGAMP. It shows the time course of activated cell extracts inducing IRF3 more quickly than they induce IFNβ

- 3G. Shows that two DNA viruses induce endogenous IRF3 dimerization and also cGAMP activity. This is nothing new, but just confirmatory - it uses human cells, and a physiologic concentration of DNA.

- By this point, there are already a few sources of evidence that cGAMP binds STING (we saw that shRNA against STING blocks the pathway in Figure 1, and we saw that cGAMP elutes with STING in affinity chromatography in Figure 2). But Figure 4 provides more evidence to confirm this. Remember how HEK293T cells lacked a response to cGAMP in Figure 1? Well now they show that STING is lowly expressed in HEK cells, and that if you transfect them to overexpress STING, then they do have a response to cGAMP. Remember how shRNA against STING blocks the pathway in Figure 1? Well that was with heat supernatants from cytosolic DNA-stimulated cells; now they repeat that experiment but with chemically synthesized cGAMP. Plus they cross-link STING to radiolabeled cGAMP and show that they migrate together.

- 4A. HEK239T cells don’t have this pathway endogenously, but if you express STING in them, you can get a response to synthetic cGAMP but not DNA. It must be that HEK239T cells lack something else in the pathway, in addition to lacking STING. This is showm by measuring IFNβ

- 4B. Same as Figure 4A but with endogenous IRF3 dimerization instead of IFNβ as readout.

- 4C. RNAi against STING abolishes the response to cGAMP (and c-di-GMP, possibly because they used huge non-physiological concentrations of these synthetic molecules) but not to RNA.

- 4D. cGAMP physically binds to STING.

Conclusions

This paper was unbelievably thorough. It established cGAMP as a second messenger in animals — until then, cyclic dinucleotides had only been known to be second messengers in Dictyostelium.

Thoughts and questions

If cGAMP is called a second messenger, then the cytosolic DNA must be considered the “first messenger”.

Sun 2013: Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway

This paper asks how cytosolic DNA induces cGAMP production. The answer: a cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) encoded (in humans) by the MB21D1 gene.

Figure by figure

- First they tried three different methods for fractioning activated cell lysates and seeing which proteins co-purify with cGAMP-synthesizing activity. This assay is fairly complicated: they fractioned L929 lysates, then for each fraction they incubated with ATP, GTP and HT-DNA and then heated, digested with nucleases and tested for cGAMP activity to see which fraction had contained the putative cGAS. This could very easily have not worked, if the synthase and DNA detector had been different proteins that eluted in different fractions. Only because cGAS both binds DNA and synthesizes cGAMP did this work. Once they had identified active fractions, they tried to use silver staining to find a protein band unique to active fractions, but they did not see any obvious unique protein bands. So instead they did mass spec, and found three candidates. One of these, a protein then called E330016A19, appeared to be homologous to a different nucleotidase (NTase) called oligoadenylate synthase, so they pursued that one further. The multiple alignment is shown in Figure 1A. In Figure 1B and 1C, the mRNA for this gene is expressed in cells that do have the cGAMP-synthesizing activity but not in those that don’t (HEK cells). Weirdly, though, the level of mRNA is very low in MEFs even though these did have activity in one of the IRF3 assays in [Wu 2013]. They were able to purchase an antibody to human cGAS from Sigma, and they show that the protein is present in THP1 cells and not detectable in HEK293T cells.

- In HEK cells which endogenously lack activity in this pathway, you can get IFNβ induction if and only if you transfect them to express both cGAS and STING (Fig 2A). The same conditions that induce IFNβ also trigger IRF3 dimerization (Fig 2B). This doesn’t work if you mutate the putative catalytic site on cGAS. Other DNA sensors besides cGAS don’t do this (Fig 2C). In Fig 2D, note that MAVS does induce IRF3 dimerization, but this IRF3 dimerization is not “transmissible” to other permeabilized cells, a test which they call the “cGAMP activity assay”.

- 2A. Induction of IFNβ RNA in HEK239T cells is dependent upon transfection with both STING and a cGAS plasmid, and doesn’t work if you mutate the putative active site in cGAS.

- 2B. Figure 2B is to IFNβ protein as Figure 2A is to IFNβ RNA. They use a FLAG tag to confirm expression of the proteins of interest, both for comparability between experiments, and because there is no antibody to mouse cGAS.

- 2C. Other proteins which people had thought might be involved in this pathway do nothing. Note that this relies on the plasmid itself inducing the IFNβ pathway by virtue of its being DNA. They do not additionally stimulate the cells with HT-DNA or anything.

- 2D. The IRF3 dimerization activity of the candidates from 2C.

- 2E. They purify cGAS from HEK293T cells using a FLAG tag and are able to reconstitute the reaction in vitro. In a moment they’ll do this in E. coli.

- In Figure 3 they test whether knockdown or overexpression of parts of the pathway affect the IFNβ response. It took us a long time to understand this figure. The transfection with the overexpression or siRNA plasmids is responsible both for inducing IFNβ (because these experimental procedures involve introducing foreign DNA) and for manipulating parts of the pathway in order to understand it. In addition, one has to stare at Fig 3B in particular for a long time to figure out that, for instance, in the middle gray column labeled “cGAS” they are both knocking down and overexpressing cGAS at the same time, and apparently the overexpression “wins” since an IFNβ response is observed. And so on. Note that Fig 3A shows that the shRNAs against cGAS are not perfect, which is why you do still get a response (indeed, a quite robust one) in Figure 3B when you knock down cGAS in cells overexpressing STING but not cGAS. Overall, it seems one could conclude that even a little bit of cGAS is sufficient to support pathway induction, whereas STING is limiting, such that if STING is knocked down then IFNβ induction is reduced. Similarly, overexpression of STING greatly increases pathway induction, whereas overexpression of cGAS doesn’t increase activity that much. Knockdown of cGAS affects IRF3 dimerization response to a DNA virus (Fig 3D) but not to an RNA virus (Fig 3E). What Fig 3F and 3G add is that shRNA against cGAS to reduce response to DNA viruses also results in a reduction in cGAMP.

- 3A. shRNA against cGAS reduces the IFNβ response to the transfected DNA.

- 3B. See discussion in the general comments on Figure 3 above. The interpretation is complicated by the fact that shRNA knockdown is imperfect and we don’t know a priori which step in this pathway is limiting. If one were doing this experiment today, one possible approach would be to use CRISPR to knock out cGAS or STING entirely in order to demonstrate the pathway’s dependence on these proteins.

- 3C. Time course of IFNβ induction.

- Figure 4 boils it down to purified components to show that cGAS, DNA and ATP + GTP are sufficient to create cGAMP. They expressed and purified a FLAG-tagged cGAS in HEK cells (demonstrated in Fig 4A). They then performed a cell-free reaction of cGAS + ATP + GTP + DNA, and showed that this reaction creates cGAMP, as measured by their cGAMP activity assay (Fig 4B). This worked with any old DNA, but only when GTP and ATP are both present as substrates (Fig 3C). It also works with recombinant, SUMO-tagged cGAS (from E. coli) and doesn’t work if you mutate the putative catalytic site (Fig 3D). The IRF3 dimerization activity induced by the products of the recombinant cGAS + ATP + GTP + DNA is seen at the same time as cGAMP production (measured by mass spec) peaks.

- 4A. They successfully purified FLAG-tagged cGAS from HEK293T cells.

- 4B. Reconstitution in vitro with nothing but DNA, cGAS, ATP and GTP allows them to induce IRF3 dimerization.

- 4C. ATP and GTP are both necessary and, together, are sufficient, for cGAMP synthesis by cGAS in the presence of DNA.

- 4D. Figure 4D is to E. coli-expressed recombinant cGAS as Figure 4B is to HEK-expressed, FLAG-purified cGAS. Also, mutating the catalytic domain abolishes activity.

- 4E. The recombinant cGAS in the minimal in vitro reaction creates cGAMP.

- Figure 5 confirms a physical interaction between cGAS and DNA. The use of streptavidin beads to pull down biotinylated DNA also pulls down GST-tagged cGAS (Fig 5A). Based on the success of the purified components reaction in Figure 4, it had to be the case that cGAS physically binds DNA, but this experiment just confirms it. Figure 5C uses deletion mutants to figure out which parts of cGAS do what. They couldn’t purify 161-212, but at least they can say that 1-212 is necessary & sufficient to bind DNA.

- Figure 6 shows that cGAS localizes largely in the cytosol. Note that the nomenclature is that S100, for instance, means “supernatant after centrifugation at 100,000g”, with P meaning pellet, etc. They found cGAS in S100 and P100 indicating it might be partly in the cytosol and party in “light organelles”, but it wasn’t in the P20, meaning it’s not in heavy organelles such as the ER. Their images of cells (Fig 6C) suggest that cGAS binds DNA in the cytosol. The message of Figure 6 is not as conclusive as the other figures.

Epilogue

Soon after these papers were published, this group came out with a third Science paper in which they showed that reverse transcription of HIV RNA into DNA triggers this pathway [Gao 2013] and a fourth Science paper in which they created cGAS knockout mice and showed that they were more likely to die when infected with herpes simplex virus [Li 2013].