Molecular Biology 27: 'Eukaryotic translation'

These are my notes from lecture 27 in Harvard’s BCMP 200: Molecular Biology course, delivered by Melissa Leger-Abraham on November 21, 2014.

Facts about eukaryotic translation

The eukaryotic ribosome has essentially the same organization as the prokaryotic ribosome: it has a small subunit (40S) and a large subunit (60S). Together they weigh in at 80S, so “the 80S ribosome” refers to the whole complex. The large contains 28S and 5S rRNAs and ribosomal proteins L1 through L50, and the small contains the 18S rRNA and ribosomal proteins S1 through S33.

The eukaryotic ribosome contains about 1.5 MDa of parts that are specific to eukaryotes. Of this figure, about 350 kDa is due to expanded portions of rRNAs, 800 kDa is proteins with no prokaryotic homolog, and 200 kDa is proteins which are eukaryote-specific but do contain a domain that has a recognizable prokarytoic homolog.

A high-resolution (3.0Å) structure of the eukaryotic ribosome was solved only recently, in yeast [Ben-Shem 2011].

The 60S subunit is said to be a “ring” containing a P-stalk (in place of the prokaryotic L7/L12 stalk), a CP, an exit tunnel, and an L1 stalk.

Structures of polyribosomes were just solved to 3.4Å using cryo-electron tomography a couple weeks ago [Myasnikov 2014].

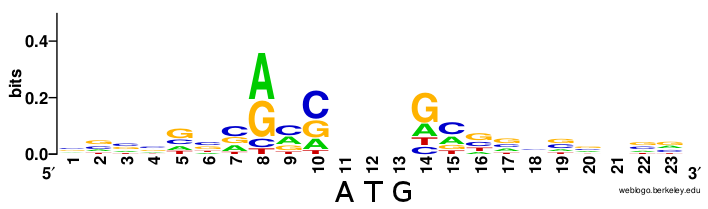

mRNAs are specified for translation by ribosomes by their 5’ cap and polyA tail. Eukaryotes have no direct equivalent of the prokaryotic Shine-Dalgarno sequence. AUG sites that get translated are preceded by a Kozak context, but unlike Shine-Dalgarno, this is not a single rigid sequence but rather a loose motif (from Wikipedia):

The mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation is reviewed in [Klann & Dever 2004]. Initiation involves several eukaryotic initiation factors, proteins whose name begins with eIF. eIF2 is compoosed of three subunits - α, β and γ - where eIF2β (or eIF2B) is a GEF. eIF2α is regulated by phosphorylation of residue S51. Kinases that can phosphorylate this residue include GCN2, HRI, PKR and PERK. These four kinases are regulated, respectively, by amino acid scarcity, heme scarcity, dsRNA, and ER stress. Thus, they each act to repress translation initiation in cases where either resources are scarce (so the cell should focus on essential proteins), or there is a risk of translating viral proteins, or there are already too many misfolded proteins in the cell. Some key concepts are reviewed in [Holcik & Sonenberg 2005].

ATF4 is an example of a protein whose translation is regulated by uORFs. The ATF4 mRNA contains two upstream ORFs, called uORF1 and uORF2. The mechanism by which this controls ATF4 translation is reviewed in Figure 4 of [Jackson 2010], and I have also touched on it briefly in BBS 230 week 9.

eIF4E and eIF4G bind each other [PDB# 1EJH] and are important for translation initiation. eIF4E-binding proteins (4E-BPs) are master regulators of translation initiation. Under conditions of inhibition, 4E-BP binds eIF4E, sequestering it from binding to eIF4G. 4E-BP is regulated by phosphorylation. When it is hypophosphorylated, it binds eIF4E, inhibting translation; when 4E-BP is hyperphosphorylated, it does not bind eIF4E, so translation is activated.

mTOR, the target of rapamycin, controls 4E-BP.

eIF4GI binds eIF4A via a HEAT repeat. It also binds many other proteins.

PDCD4 is a tumor suppressor upregulated in apoptosis and downregulated in some cancers. It inhibits the eIF4G/eIF4A interaction.

Translation is also regulated by RNA secondary structure. Some RNAs contain an iron response element (IRE) which is a specific nucleotide sequence in the 5’ UTR. When iron is low, IRE-binding protein binds this sequence, inhibiting translation. When iron is high, IRE-binding protein releases the mRNA and allows translation. This mechanism regulates the translation of, for instance, ferritin, which is responsible for iron transport. This mechanism somehow relates to RNA secondary structure.

Note that IRE is a totally different thing than IRES, the latter of which stands for Internal Ribosome Entry Sites. Some viruses have evolved to be able to undergo translation initiation without eIF4E, by using IRES. According to Wikipedia IRES is a nucleotide sequence that allows translation to start in the middle of an RNA. As far as I can tell from the lecture slides, this appears to involve a stem-loop structure. You can study IRES using a dual reporter gene encoding RFP and GFP with or without this stem-loop structure (IRES sequence?) in between them.

An in vivo experiment conrirmed that 4E-BP represses translation initiation, and that this is important for cancer [Avdulov 2004].

A fluorescent polarization assay using fluorescein allows you to study something related to all this. This was used to discover a small molecule called 4EGI-1. This molecule turned out to inhibit translation by disrupting the eIF4E/eIF4G interaction and it inhibits the growth of human cancer xenografts (into mice??).

Recoding events cause a ribosomal frameshift. Many viruses are capable of doing this. HIV-1 has a programmed ribosomal frameshift. HIV-1 encodes a Gag domain followed by a Pol domain in the -1 frame relative to Gag. 90% of translation events result in just a Gag protein. In 10% of cases, a -1 frameshift occurs during translation, creating a Gag-Pol fusion protein. Gag contains MA, CA and NC which are viral structural proteins, while Pol cintains PR, RT and IN, which are viral enzymes. This 9:1 ratio of Gag to Gag-Pol has been shown to be important for viral replication [Dulude 2006]. This frameshift is programmed by a “slippery sequence” in the RNA.

Ribosome profiling is an important genome-wide technique for studying translation. This was the subject of BBS 230 week 9. Earlier this year, Nick Ingolia wrote a review of this whole technique / field of study [Ingolia 2014]. Because translation initiation is the limiting step in translation, you usually see a pileup of ribosome footprints over the initiation site.