Structures of PrPC

After my nearly three years of studying prions, structural biology remains an area I know almost nothing about. Recently I set about trying to rectify this and understand a bit of the capabilities and limitations of structural biology with regard to prions. The real challenge here is understanding what we know and don’t know about the structure of PrPSc, but for starters, in this post I’ll address the easier question of the structure of PrPC, which has been solved.

Something I’ve come to appreciate in my molecular biology class this semester is that X-ray crystallography and NMR are both old, tried-and-true technologies, and one major reason they’ve remained non-trivial to execute after all these years is that they both require extremely pure preparations of a protein or complex of interest, with virtually every copy of the molecule in the exact same conformation. For example, a challenge in creating a uniform crystal of the DNA double-strand break-binding protein complex Ku70/80 was that if you put in a piece of DNA, Ku70/80 can bind to either of its ends, so that now not every molecule is in the exact same position. Overcoming this problem required the clever trick of using a piece of DNA that has a hairpin at one end, such that only one end is recognizable as a double-strand break [PDB# 1JEY, Walker 2001].

PrPC’s structure was finally experimentally determined [Riek 1996] over a decade after it was first purified [Prusiner 1983, Prusiner 1984]. As far as I can tell, two of the major obstacles which made PrPC difficult were:

- Its flexible N terminus doesn’t want to adopt the same conformation in every copy of the molecule, and

- It is poorly soluble in water without detergent, making it hard to obtain sufficiently high concentrations (e.g. the 0.8 mM eventually achieved in [Riek 1996])

In addition, according to [Riek 1996], in early attempts to produce recombinant PrP it was found that bacterial proteases would often cleave the protein at residues 112, 118 and 120, making it impossible to obtain the intact protein. A resolution to all of these problems awaited Simone Hornemann’s development of a protocol for purifying recombinant MoPrP121-231 from E. coli [Hornemann & Glockshuber 1996]. This C-terminal segment of PrP proved far more soluble in water than the full-length protein, and it readily folded into a uniform conformation. With this enabling insight, the first structure of PrPC was soon solved via solution NMR [Riek 1996]. This solution came from the laboratory of none other than Kurt Wuthrich, who had pioneered the use of solution NMR for biomolecules and would later win the 2002 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

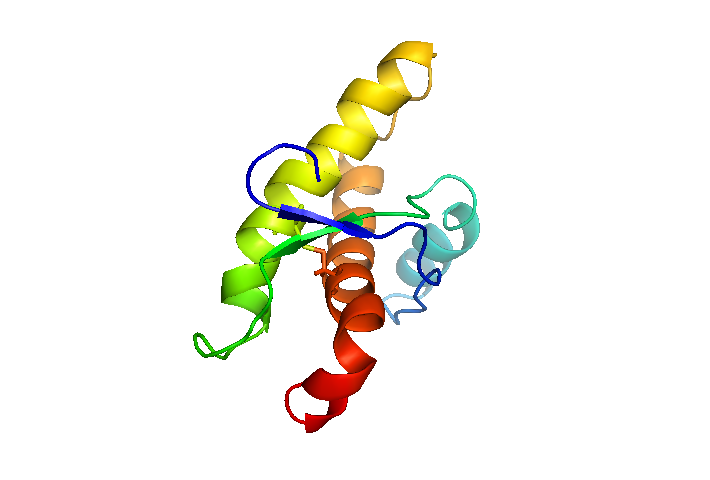

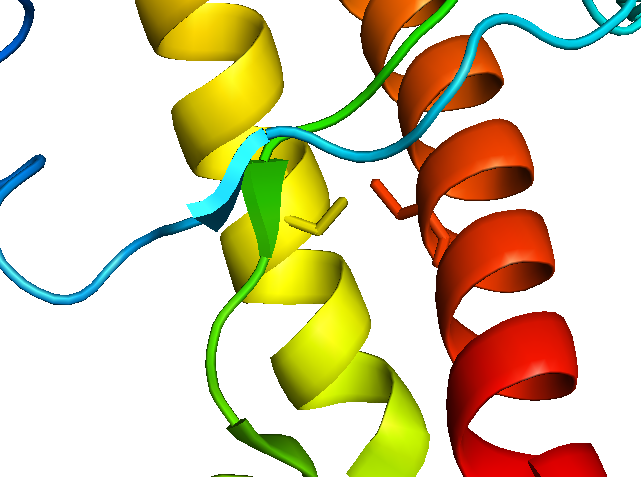

The structure they determined is [PDB# 1AG2], so I fired up PyMOL to have a look at it.

bg_color white

fetch 1ag2

hide everything

show cartoon

spectrum

show sticks, resi 179 or resi 214 # show the disulfide bridge

Here, I’ve colored PrPC by residue number, so that the bottom-most red end is where the GPI anchor would be attached and insert into the membrane, and the blue tip off to the upper left would lead to the rest of the N terminus. You can see the disulfide bond between α-helices 2 and 3.

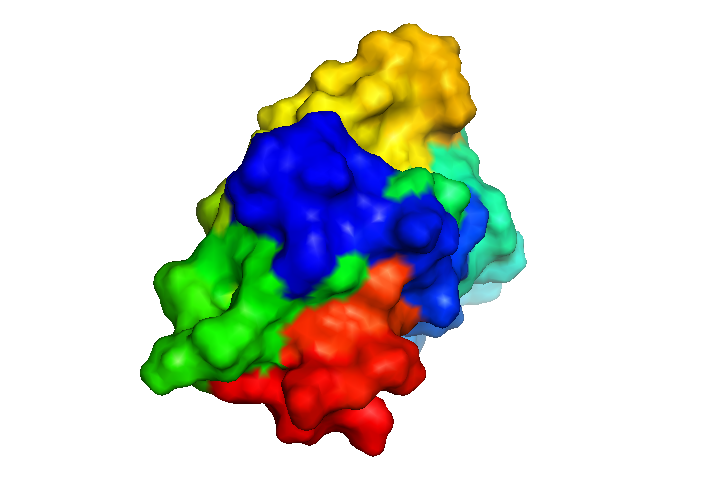

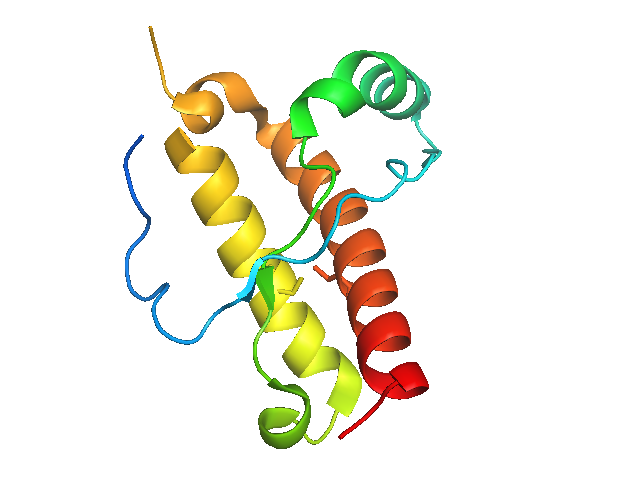

That cartoon view makes it seem that there is plenty of space in the protein, in contrast to how everyone calls the C terminus a “globular domain”. So next I switched to surface view instead:

hide cartoon

show surface

That’s better - now it at least looks solid. Still, it is hardly a ball - its surface seems to be covered with an awful lot of divots and ridges, which you can see if you shake it around:

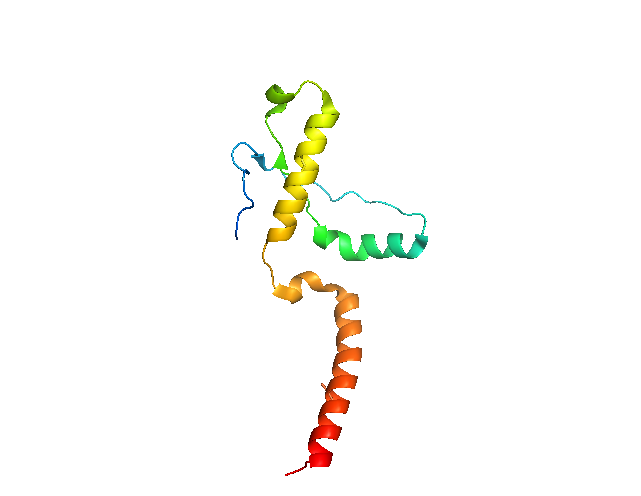

The structure of PrPC has now been determined dozens of times (different species, different mutants, etc.) since Roland Riek and Kurt Wuthrich’s original NMR structure [reviewed in Surewicz & Apostol 2011]. The first X-ray crystal structure came five years later, and used a slightly longer C-terminal fragment: HuPrP90-231 [PDB# 1I4M, Knaus 2001]. The assignment of residues to α-helices and β-sheets is identical to that of [Riek 1996], but the tertiary structure looks utterly different, and the cysteines of the disulfide bond (sticks in red near bottom and yellow near top) do not face each other:

bg_color white

fetch 1i4m

hide everything

show cartoon

spectrum

show sticks, resi 179 or resi 214 # show the disulfide bridge

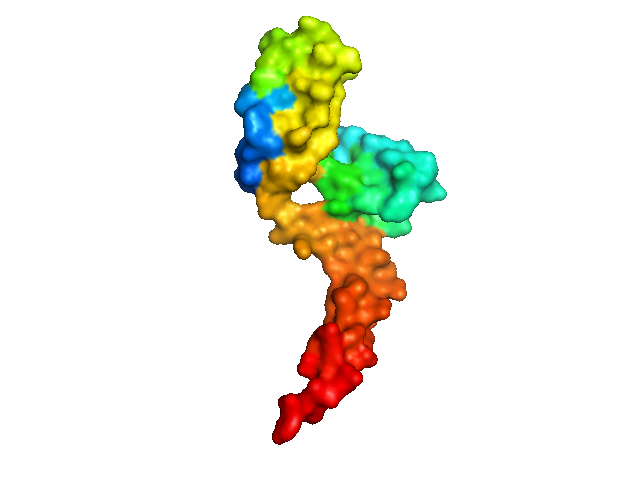

Even if you view it as a surface, there’s a big hole in the middle:

hide cartoon

show surface

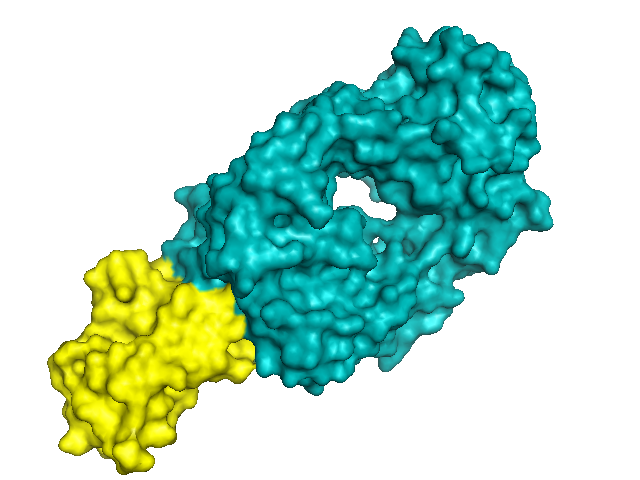

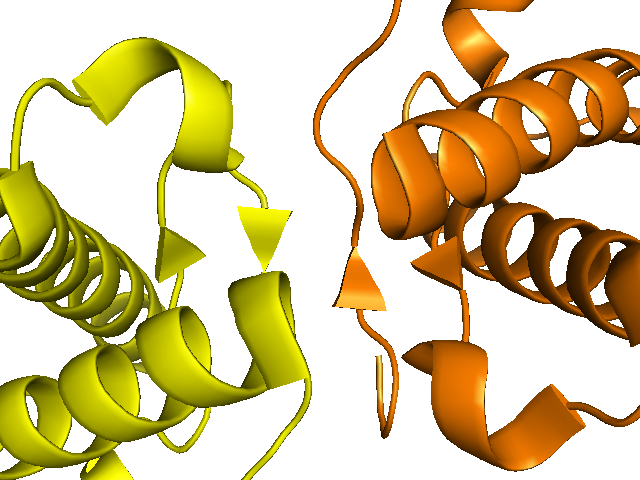

It turns out that both of these differences are because the protein crystallized as a domain-swapped dimer. α-helix 3 is swapped between two PrPC molecules, the disulfide bond is intermolecular, and an intermolecular antiparallel β-sheet forms.

To visualize the dimer in PyMOL, you need to generate the symmetry mates:

symexp sym,1i4m,(1i4m),3.0

hide everything

show cartoon, 1i4m

show cartoon, sym02000000

show sticks, resi 179 and (1i4m or sym02000000)

show sticks, resi 214 and (1i4m or sym02000000)

Although they don’t appear to line up perfectly, the cysteines of the disulfide bond are at least across from each other now:

If we show only residues >191 in one copy of the protein and only residues <191 in the other copy, it starts to look much more like the NMR structure:

hide everything, 1i4m and resi 191-231

hide everything, sym02000000 and resi 1-190

Now the surface looks more solid, too - no large gaps:

show surface, 1i4m and resi 1-190

show surface, sym02000000 and resi 191-231

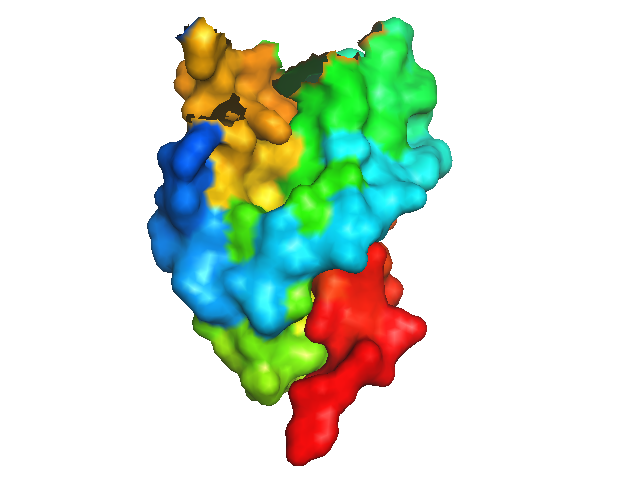

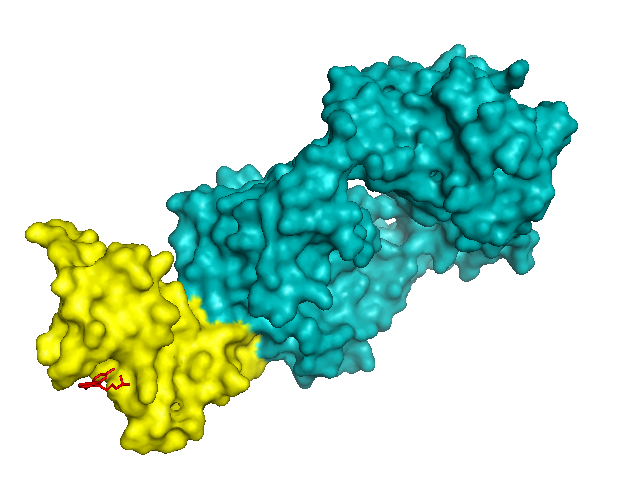

Later on, other groups crystallized PrPC in complex with antibody Fabs, and obtained crystals of PrP that look much more like the NMR structure. It is not clear to me if using an antibody is necessary to prevent PrP from domain-swapping during crystallization, or if these investigators were simply interested in the structure of PrP when bound to an antibody. In any case, the first of these was MRC Prion Unit’s structure of HuPrP 119-231 bound to ICSM-18 [PDB# 2W9E, Antonyuk 2009].

bg_color white

fetch 2w9e

hide everything

show surface

color teal, chain L # light chain ICSM-18 fab

color teal, chain H # heavy chain POM1 fab

color yellow, chain A # HuPrP

PrP (yellow) is a tiny protein - it even appears small compared to the Fab (teal), which in turn is much smaller than a real antibody. Although PrP here has a structure close to that obtained via NMR, and is not domain-swapped, it does form an intermolecular beta-sheet with its neighbor:

hide everything

symexp sym,2w9e,(2w9e),3.0

hide everything

show cartoon, sym02-10000 and chain A

show cartoon, sym08000000 and chain A

color orange, sym08000000 and chain A

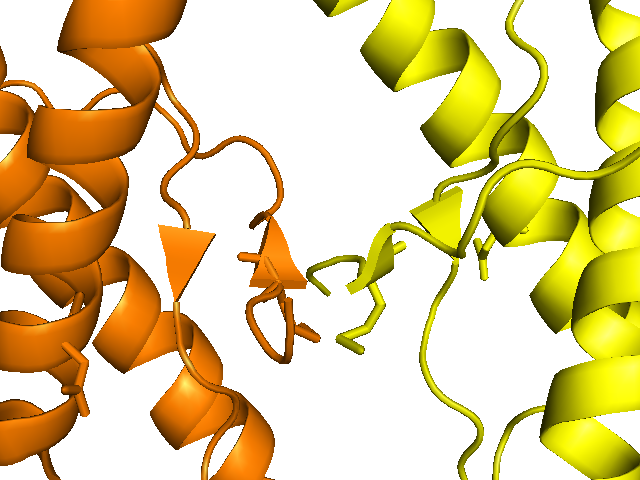

One review I read [Surewicz & Apostol 2011] noted that either of these dimeric interactions - the intermolecular beta sheet or the domain swapping - might or might not mimic an interaction that PrP does in vivo during PrPSc formation. It is tempting to speculate, particularly since codon 129 is located in one of those beta strands and is known to influence PrP conversion efficiency, but there is no hard evidence.

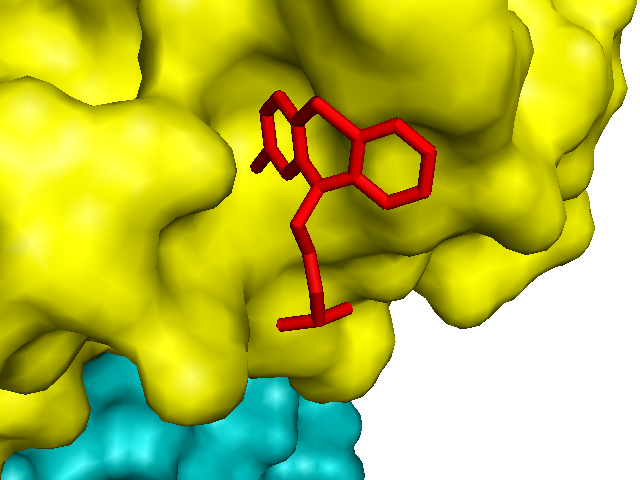

Having learned how to use PyMOL and examine these structures, I also went back and looked at the crystal structure of mouse PrP bound to chlorpromazine and POM1 which Michael James and Adriano Aguzzi reported earlier this year [PDB# 4MA8, Baral 2014] and which I blogged about a few months ago:

bg_color white

fetch 4ma8

hide everything

show surface

color teal, chain L # light chain POM1 fab

color teal, chain H # heavy chain POM1 fab

color yellow, chain C # PrP

color red, organic # small molecule

show sticks, organic # small molecule

Sure enough, chlorpromazine is shown sticking into one of those divots on the surface of PrP:

Another structure I had always wanted to understand better is that of crystallized HuPrP D178N 129M, the mutant protein responsible for fatal familial insomnia [PDB# 3HEQ, Lee 2010]. The authors crystallized HuPrP 129M or 129V with either a wild-type sequence, the D178N mutation or the F198S mutation. Surprisingly, the wild-type protein formed a domain-swapped dimer, but the mutants didn’t - they instead formed intermolecular beta-sheets not unlike those from [Antonyuk 2009].

bg_color white

hide everything

show cartoon

color yellow, chain A

color orange, chain B

symexp sym,3heq,(3heq),3.0

hide everything

show cartoon, chain A and 3heq

show cartoon, chain B and sym07000000

show sticks, resi 129

show sticks, resi 178

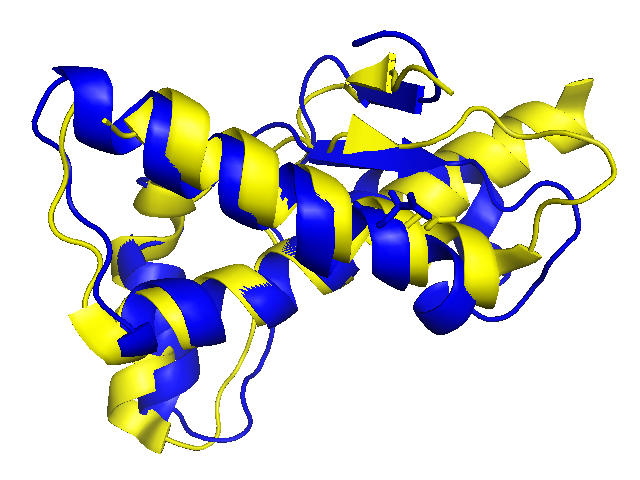

The authors state that, compared to the impact of the F198S mutation on structure, “the structural consequences of the FFI and CJD D178N substitution are more subtle”. If they’re subtle even to the structural biologists, I expect I will have trouble discerning anything at all, but I figured I’d try and align the D178N structure with the HuPrP structure from [Antonyuk 2009]:

hide everything, sym07000000

hide sticks

fetch 1ag2

hide everything, 1ag2

show cartoon, 1ag2

color blue, 1ag2

align 1ag2, 3heq and chain A

show sticks, resi 178 and (3heq and chain A or 1ag2)

The two structures align reasonably well, with a root mean squared distance (RMS) of 2.3 Å2 between corresponding atoms. Visually, the structures look broadly similar, but they do seem to diverge a bit around the beta sheets (D178N in yellow and wild-type in blue).

As mentioned above, there are yet dozens of other structures of PrPC, many of which are reviewed in [Surewicz & Apostol 2011]. While a lot of the insights about these structures remain mysterious to me, being able to at least have a look and play with them has helped me to understand a bit more of the observations that the authors have made in their papers about these structures.