Protein folding 05: Partially folded intermediates

These are my notes from week 5 of MIT course 7.88j: Protein Folding and Human Disease, held by Dr. Jonathan King on March 5, 2015.

Assignment 4

The readings for this week are:

- Brems 1988, part of the effort to figure out how recombinant bovine growth hormone aggregates

- Mitraki & King 1989, a review written for a chemical engineer audience, as that was the training background of most of the workers who the nascent biotech industry had hired to help figure out how to purify proteins.

- Nall 1990

Brems 1988 Stabilization of an associated folding intermediate of bovine growth hormone by site-directed mutagenesis

When this paper was written, recombinant proteins were still relatively new, and none had yet received regulatory approval for use in agriculture or drugs. Attention was focused on bovine growth hormone, a ~190-residue peptide, for which Genentech had cloned the gene and filed a patent in 1984 [US4880910]. By 1990, Monsanto was pushing for FDA approval for the use of rBGH in cows, which was expected to increase milk yield by 10-25% [Peel 1981]. They eventually received approval in 1993 (mentioned here and here).

By the time this paper was written, it was known that rBGH, if partially denatured, could form an “associated intermediate”. The authors had proposed that associated intermediate was off-pathway:

By “associated” they meant that the intermediate was multimeric (we now know it was a dimer, see below). This paper describes a series of refolding and unfolding experiments on wild-type and mutant K112L rBGH. The mutant is predicted to expand the hydrophobic surface of rBGH helix 3 (residues 107-128) in a way that stabilizes helix-helix packing. The experiments collectively point to a model in which formation of the associated intermediate is nucleated by intermolecular association of the helix.

The first line of evidence is Figure 2. They perform equilibrium denaturation of wild-type and mutant rBGH and measure CD spectra. Plotted are the CD absorption at 222 nm, which indicates alpha helices, as described here), and 300 nm, which is more esoteric. As noted in this overview, tryptophan absorbs at 300 nm. rBGH contains exactly one tryptophan residue, W86. The 300 nm absorbance is somehow indicative of the local conformation around that tryptophan.

As you increase GdnHCl concentration, the mutant protein starts losing its helices (222 nm absorbance) sooner, but then loses them more gradually. Interpretation: a partially unfolded intermediate is more stable in the mutant. And, as you increase GdnHCl, both proteins go through a phase with reduced 300 nm absorbance (perhaps because tryptophan is more buried?), but for mutant protein, this trough is deeper and wider. Interpretation: the stabilized intermediate, which exists for both species but is more favorable for the mutant, is an “associated” state where tryptophan is in an altered conformational environment.

In the above experiments they varied [GdnHCl]. Next, they fix [GdnHCl] at 3.7M, and vary the protein concentration instead. They use 300 nm absorbance on CD as a proxy for the presence of the “associated intermediate”. It takes a much higher protein concentration to bury tryptophan in the wild-type to the same degree as it is in the mutant protein even at low concentrations (Fig 4).

They then abandon equilibrium folding/unfolding, and switch to kinetics. Across a range of GdnHCl concentrations, mutant rBGH is slower to fold and quicker to unfold, as indicated by absorbance at 290 nm (Fig 5). The kinetic curves for 300 nm absorbance upon dilution from 6M to 2M GdnHCl are starkly different - the wild-type folds almost immediately, while the mutant takes a long time.

They also found that the mutant protein forms an opaque (scatters light at a visible 450 nm) solid more readily than the wild-type (Figure 7). The authors called this process precipitation, but today we would call it aggregation.

Epilogue: This work was all done before the structure of rBGH was known. Once a high resolution structure was solved, it became clear that the so-called Iassoc was in fact a domain-swapped dimer. It had the same helix-helix interaction as the native protein — helix 2 to helix 3 — only it was intermolecular instead of intramolecular. Interestingly, human growth hormone differs from that of bovine growth hormone in the amino acids on this helix 2 / helix 3 interface, and is much easier to express and purify as a result. Also of note, the Brems paper identified a mutation, rBGH K112L, which promoted aggreagtion. It was later discovered that you could introduce mutations that would reduce the propensity to aggregate, which is of course a rather useful thing. Much of the recombinant human insulin that is produced commercially as a drug today is insulin lispro, which swaps two adjacent residues (KP instead of PK) to reduce dimer and hexamer formation, apparently making it possible for larger doses to be administered without aggregation occurring. Officially, these sorts of altered peptides are called “insulin analogs” or “insulin receptor ligands” rather than “insulin”.

Lecture notes

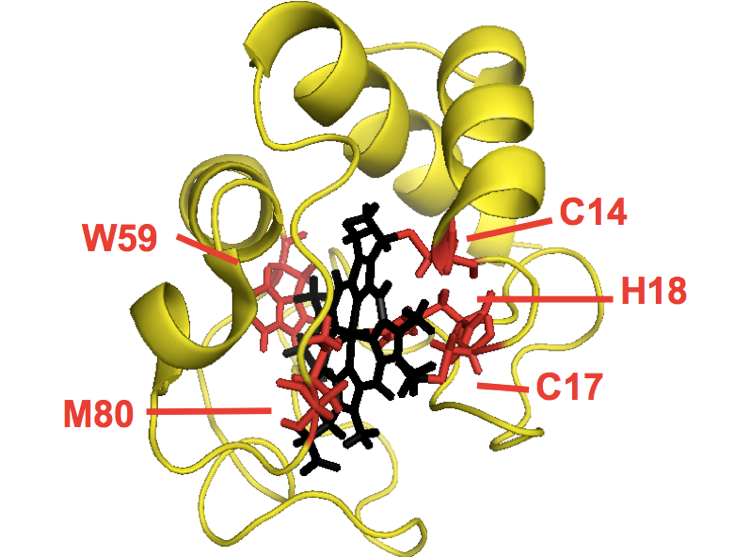

Cytochrome c

Cytochrome c is a 104-residue protein responsible for moving electrons around during oxidative phosphorylation. It is an ancient protein shared among all eukaryotes. The protein covalently binds a heme molecule via two cysteine residues, C14 and C17, and coordinates it with H18 from the right and M80 from the left. The nitrogen in W59 also hydrogen bonds to the carboxylate in the heme. The gene is autosomal, but the protein localizes to the mitochondria. The classic experiments were all done on cytochrome c purified from horse heart. It was later discovered that yeast have two cytochromes, only one of which has disulfide bonds, thus allowing purification. Cytochrome c contains three helices, at 1-11, 91-104 and somewhere in the 60s-70s.

The original structure of horse heart cytochrome c does not appear to be in PDB, but I found a later structure [PDB# 1OCD, Qi 1996]:

fetch 1ocd

bg_color white

hide everything

show cartoon

show sticks, organic

color yellow

color red, resi 14 or resi 17 or resi 18 or resi 59 or resi 80

show sticks, resi 14 or resi 17 or resi 18 or resi 59 or resi 80

color black, organic

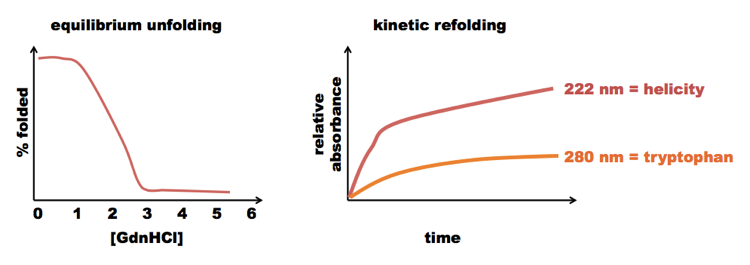

Noll et al (?) measured equilibrium unfolding and kinetic refolding of cytochrome c in GdnHCl, and got results roughly something like this:

The equilibrium experiments gave a clean curve, with a monotonic first derivative - no indication of an intermediate. But in the kinetic experiments, the protein regained its helices more quickly than it changed the local conformation around its tryptophans. This implied that there must be some partially folded step on the way to full folding.

To characterize the folding pathway, [Roder 1988] used hydrogen/deuterium exchange, measuring exchange between hydrogens in a protein and deuterium in solution. Hydrogens in C-H bonds are not exchanged. But hydrogens in O-H and N-H bonds can exchange. The N-H bond on the backbone exchanges very slowly, because this amide is hydrogen-bonded to a carbonyl in an alpha helix or beta sheet. The hydrogens on O-H and N-H bonds in the side chains of residues S, T, R and K undergo exchange readily. The exchange rate for amide hydrogens is maximized at pH ~9. The readout for H/D exchange is nuclear magnetic resonance. H-NMR only detects hydrogen, not deuterium. Therefore H-NMR can give you a quantitative readout of how much each position on the protein has undergone exchange.

Cytochrome c has 100 amide hydrogens, and for about 50 of them, the exchange rate is very different beteween the folded and unfolded state. Cytochrome c is very basic due to (in horse) 17 lysines (out of 104 residues total).

Cytochrome c fully denatures at 2M GdnHCl or higher. In Noll’s experiments they had it denatured in 4.2M GdnHCl at pH 6 in 100% D2O, so it should be fully deuterated. They would then inject it into a chamber where it would be diluted to 0.7M GdnHCl, still in D2O. Then they would wait X amount of time and then spray (or “shpritz”) H2O at pH 9.3 at 10°C, where X varies from 0.4ms to 10s. Then they wait another 50ms and then quench the exchange by dropping the pH to 5.3 at 0°C. This 10,000-fold increase in [H+] is enough to reduce the exchange rate by ~100-fold. They then collect the folded molecules and subject them to H-NMR. Note that analyzing these data requires already knowing how the H-NMR spectrum of cytochrome c maps onto particular atoms in the structure. That work had been done years earlier.

The resulting data are presented in the bottom panel of Figure 3. When the protein only had 0.4ms to re-fold, it was ~100% unfolded when it hit the H2O, and so all of its amide deuteriums underwent equally rapid exchange. As the time allotted for re-folding increased, different parts of the protein folded at different rates. Exchange in the N-terminal and C-terminal helices both dropped by >50% if the protein was given even so much as 0.1s to re-fold. The “60s and 70s” helix took much longer, over 1 second to fold enough that hydrogen exchange dropped below 50%. Thus, the helices at the ends folded first, and the intermediate helix folded subsequently. The fact that the kinetics of C and N terminal helix folding were so nearly identical also indicated that the folding of these two was cooperative with each other. It might be that the hydrophobic side chains dock the denatured C and N termini to one another, enabling each one to then form a helix.

It was later shown that in the in vitro refolding of cytochrome c, before reaching the native state where M80 makes a ligand with the iron in the heme, there is an intermediate where a different methionine does this. Some investigators felt that the existence of an “incorrect intermediate” in the in vitro refolding pathway discredited all of the experiments such as that of Roder et al, above. But it’s unlikely that the folding of cytochrome c is actually a simple, elegant one-step process in vivo. In vivo, cytochrome c is translated in the cytosol, localizes to the mitochondria and has to be transported through the mitochondrial membrane before it ever encounters a protein called cytochrome c heme lyase, which creates the covalent bond between the protein and the heme, which may be the final step in its folding.

Nall 1990 Proline isomerization and folding of yeast cytochrome c

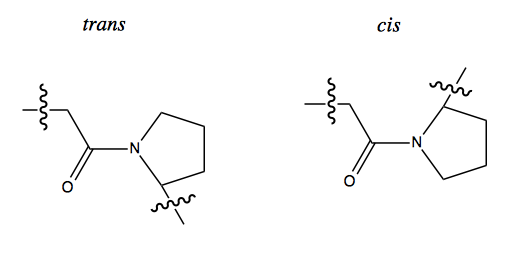

Nall expressed a series of cytochrome c mutants in yeast and looked at cis/trans isomerization of proline. Proline is the one amino acid for which the backbone lacks double bond character in the C-N bond. This property allows free rotation of this bond between cis and trans isomers in an unfolded polypeptide, but not in a folded protein, because then the proline is constrained by surrounding tertiary structure.

Based on this observation, Nall conceived a famous experiment called the double jump experiment. You start with a natively folded protein, in which the proline is either all cis or all trans depending on the conformation of that particular protein. You then briefly add denaturant, then remove it again. If you add enough denaturant for long enough, the proline will all go to 50/50 cis and trans; if you do it for a short time, only a minority of molecules will unfold enough to allow proline to isomerize. Then when you remove the denaturant, any molecules where prolines remained in the native orientation will be able to re-fold very quickly, while molecules where proline isomerized will have a very slow time re-folding. This gives you a way to measure the degree of protein unfolding.

Nall performs these experiments on a series of P→G mutants of cytochrome c, and measures the “slow folding” conformer via absorbance at 418nm or fluorescence at 350nm. The only P→G mutant that significantly affected folding kinetics was P76G. Interpretation: isomerization of P76 is a rate-limiting step in the folding of cytochrome c.

It has been debated whether proline isomerization is relevant to folding in vivo. There is now clear evidence that, for at least some proteins, it is indeed relevant.

Nall’s chapter is an epic fail in terms of data visualization - instead of plotting the curves on the same plot, they put each one on its own plot with different, unlabeled, axis extents, such that all curves look the same even though they are very different.

Jacob & Monod

Many of the earliest-studied proteins were studied not because of their biological or medical importance, but simply because they were available in sufficient quantity to do research on: RNAse, cytochrome c, S peptide, and so on. A sea change occurred when Jacob and Monod, in France, came to protein folding from a starting point of genetics. They were interested in beta galactosidase, and they already had a whole series of mutants from genetics experiments. Beta galactosidase is a larger protein than the others people had studied - 125 kDa - and exists as a tetramer, so it was harder to fold.

Their key experiment was a double jump of sorts. They began with a fully folded protein, then dipped it briefly into anywhere from 0M to 6M GdnHCl, then put it back into a folding buffer. Curiously, they found that if the protein was dipped in 6M GdnHCl, the folded form could be recovered with a high yield in the buffer afterward. But if they dipped the protein into 3M GdnHCl, recovery in buffer was very low. The dip in yield at ~3M GdnHCl was dubbed a “trough”. The interpretation was as follows. There were two intermediates, I1 and I2, such that the folding pathway is U → I1 → I2 →. I1, but not I2, is prone to aggregation. 3M GdnHCl is just enough denaturation to get a lot of protein to I1 all at once, such that it irreversibly aggregates off-pathway. Whereas if you go all the way to 6M, you are unfolded, and then can quickly refold through I1 and I2 to reach N.

This lesson actually led to a practical methodology for purifying recombinant proteins. Consider that there are two ways to do a 1:10 dilution of a denatured protein into buffer. You can first put 0.9 mL of buffer in an Eppendorf tube, then add 0.1 mL of protein to it. Or you can put the 0.1 mL of protein the Eppendorf and add 0.9 mL of buffer on top of it. The latter method yields more rapid mixing, just like how tea brews more quickly when you pour hot water on top of it than when you drop the teabag into hot water. Thus, the latter method yields a more rapid transition from, say, 6M to 0.6M GdnHCl, allowing fewer molecules to be in a local environment of 3M GdnHCl at any one time. Even better, biotech companies have developed the method of dripping protein solution into buffer a single drop at a time. Remember that aggregation is a concentration-dependent phenomenon, and neither U nor N are prone to aggregation, only I1. Thus if you add protein one bit at a time, you gradually accumulate N, but at any given moment, the concentration if I1 is very low, thus minimizing aggregation. Another trick is to perform refolding at the lowest possible temperature that still allows acquisition of the native state. That’s because the partially folded intermediates are always more “thermolabile” than the native protein.

Implications for multimeric proteins

When studying (or commercializing) monomeric proteins, you can work at low concentrations in order to minimize aggregation. But if your protein exists natively as a tetramer, then in order to make the tetramer, the protein needs to be at a high enough concentration for the monomers to find each other. Indeed, you can reason that this problem must exist in vivo as well - any protein that needs to function as a tetramer has to be highly-enough expressed in order to form tetramers, at which point it will also be highly-enough expressed to start aggregating. This motivates a need for chaperones.