Using human loss-of-function variants to evaluate drug targets

Our new paper on using human genetic data — loss-of-function (LoF) variants in the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) — to evaluate potential drug targets is now up on bioRxiv: [Minikel 2019]. This is a companion paper (the first of many!) to the fantastic new gnomAD flagship paper, [Karczewski 2019].

The story of this study goes back four years. Some of this is based on analysis I did on the original ExAC dataset in 2015 when I was still in the MacArthur lab. The goal at the time was to figure out how to use the stats on loss-of-function variants in ExAC to figure out which genes were good drug targets, and which weren’t. The answer, we found, was that while deep curation of LoF variants in a gene of interest could be hugely informative, there was no one-size-fits-all recipe, no plug-and-play formula for voting thumbs up or down on a gene. For example, population data like ExAC allow us to quantify constraint — a measure of how much natural selection has depleted away the naturally occurring LoF variation in a human gene, or in other words, how intolerant the gene is of LoF. But it turns out that successful drug targets can be highly LoF-intolerant, suggesting they may be essential, or highly LoF-tolerant, suggesting they are largely dispensable.

At the time, we thought of this as an uninteresting result, and we didn’t proceed to write it up or do anything with it. But in the intervening years, experience has changed my perspective. Sonia and I have had literally hundreds of discussions with people about our efforts to develop an antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) against the prion protein gene (PRNP) as a drug for prion disease. One question people always ask, without fail, is something along the lines of: how can we know if it is safe to lower prion protein (PrP), if we’ve never seen a PrP “knockout” human? We always gave the best answer we could: an ASO won’t lower PrP by 100%, and there is a very mild phenotype in homozygous knockout mice and none in hets [Bremer 2010], and we’ve seen healthy humans who are heterozygous “knockouts” [Minikel 2016], and most importantly, we know that PrP causes the disease and that if we can lower it that will make a difference. PrP is basically the best drug target you could ever ask for.

This is a good answer, and most people are satisfied by it. But, over time, we also came to realize that there is widespread confusion about what makes a good drug target. In some ways, I blame PCSK9: it is a fantastic story that has helped to make people aware of the still-largely-untapped potential of using human genetics to drive drug discovery. But it is almost too perfect, and may lead some people to set a very high standard for what human genetic data are needed to validate a drug target — a standard that many or most of the approved drugs you and I take every day would not actually pass.

So a few months ago I wrote a blog post about using human genetic data, specifically loss-of-function variants, to try to evaluate potential drug targets. I was surprised by the reception it got online — the post got over 1,000 pageviews in the first two days, possibly a record for CureFFI.org. It turns out a lot of people out there are thinking hard about how human genetics can inform drug discovery. Daniel MacArthur soon sent me a message to suggest we work together to write a paper on this theme. Together with an awesome set of collaborators, we set out to update and improve the original blog post analysis, and expand our analysis to address a host of other issues too, answering questions such as:

- Does a gene’s tolerance to LoF variants predict whether it is a good drug target?

- Can a gene that is highly intolerant of LoF variants be safely targeted?

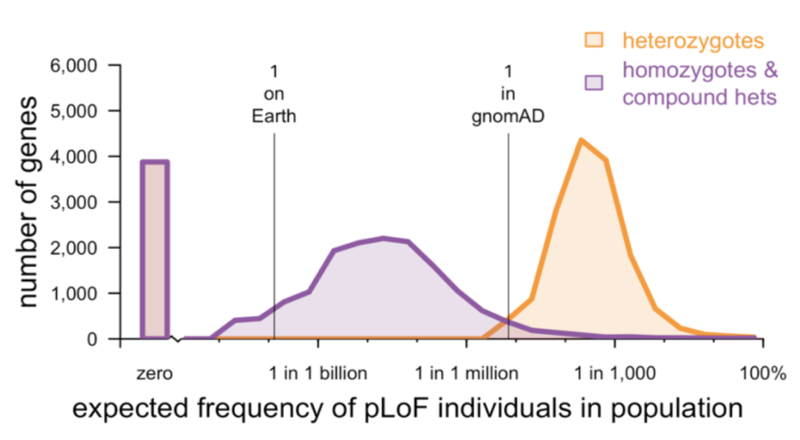

- Is it reasonable to expect to identify human “knockouts” for every gene of interest?

- Does a lack of human “knockouts” for a given gene imply that this genotype is not viable?

- Which populations, or types of populations, should one focus on if the goal is to identify human “knockouts”?

- How should candidate LoF variants be filtered and curated before initiating recall-by-genotype efforts?

- What can be learned from the frequency and distribution of LoF variants even before any LoF individuals are recalled for deeper phenotyping?

Along the way, we had a chance to provide deep curation of a few neurodegenerative disease genes that I’m interested in, such as HTT and MAPT, and to update what we wrote about human loss-of-function variants in PRNP three years ago with the latest gnomAD data.

Please have a look: [Minikel 2019], and feel free to leave a comment (either here, or on the bioRxiv page) to let us know your thoughts!