CJD Foundation Family Conference 2019

These are my notes in plain language from the CJD Foundation Family Conference in Washington, D.C., July 12-14, 2019.

Richard Knight: Keynote - Prion disease, an introduction

The term prion disease came into use after Stanley Prusiner discovered the causal protein, prion protein (PrP) [Prusiner 1984] and the mechanism by which it causes disease: transmissible protein misfolding. The disease had been given various historical names corresponding to different clinical characterizations in humans — Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), Gerstmann-Straussler-Scheinker disease (GSS), fatal familial insomnia (FFI), and so on — or corresponding to different animal species (scrapie, chronic wasting disease, and so on). Ironically, it is now believed that Hans Creutzfeldt’s original case, and 3 of the first 5 cases reported by Alfons Maria Jakob, did not in fact have the disease we now call CJD, nor any other form of prion disease [Katscher 1998].

Prion disease is casued by the prion protein (PrP). The disease happens when the normal prion protein (PrPC), which we all have in our brains, changes shape into a toxic, self-propagating form called a prion (PrPSc). This change in shape, or misfolding, can come about by chance (sporadic prion disease), a DNA mutation (genetic prion disease), or an exogenous infection (acquired prion disease).

Diagnostics for prion disease have improved dramatically in the 30+ years that Dr. Knight has been working in this field. Some of the best diagnostic tools rely on detecting the underlying molecular pathology of the disease — PrP misfolding. This can be detected by exponentially amplifying in vitro the prions present in someone’s spinal fluid or other fluids or tissues, using techniques called real-time quaking induced conversion (RT-QuIC) or protein misfolding cyclic amplification (PMCA). Detecting abnormal PrP by these means is not the same as detecting infectivity, and there has never been any evidence for transmission of prion disease by casual contact.

Prion disease is still incurable today. There have been 40+ attempts to treat patients with drugs; none has proven effective, and most were never evaluated in any rigorous or systematic way [Stewart 2008]. There are ongoing efforts to develop therapies. Dr. Knight offered a note of caution that there are two different potential treatment situations. One is treating people who are already ill, where he fears is a risk that by the time of diagnosis some patients might be too advanced for even an effective treatment to do them any good. The other situation is preventing disease in people who carry genetic mutations that cause prion disease, and Dr. Knight thinks this is our best way forward to develop an effective therapy.

In Q&A, one audience member asked whether there are things that trigger the disease in mid-life. Dr. Knight said that no one has found any evidence for any specific triggering event that brings about the onset of disease. For example, when they have compared people admitted to the hospital with prion disease versus other indications, they found that there was a similar rate of stressful or traumatic events in the preceding months [Harries-Jones 1988]. (I’ve reviewed some of these studies, specifically those pertaining to surgical procedures, in this post).

Simote Foliaki: Cerebral neuronal dysfunction associated with human prion diseases

The basic question of Dr. Foliaki’s study is what biochemical changes in the brain predispose individuals to neuronal dysfunction in prion disease. Specifically, he wants to learn what changes are happening in brain cortex tissue leading up to the onset of disease. Dr. Catherine Haigh’s lab at NIH has recently developed a method for growing cerebral organoids or “mini-brains” in the lab [Groveman 2019], and Dr. Wenquan Zou at Case Western has been collecting skin punch samples from research volunteers at risk for genetic prion disease. Using stem cell technology, Dr. Foliaki has reprogrammed these skin cells into stem cells and then grown them into organoids to be able to compare “mini-brains” with or without the E200K mutation that causes genetic prion disease. He is testing these organoids for the presence of abnormal PrP and for electrophysiological changes.

Graham Jackson: Development of a quantitative, real-time protein misfolding cyclic amplification (PMCA) reaction

Diagnosis of, and research on, prion disease have been transformed by techniques to detect abnormal PrP through exponential in vitro amplification of misfolding. While there are many different specific protocols, there are two major categories of these techniques. Real-time quaking induced conversion (RT-QuIC) uses heating and shaking to amplify PrP misfolding [Schmitz 2016], while protein misfolding cyclic amplification (PMCA) uses intermittent sonication [Morales 2012]. The two approaches can be useful for different purposes, for example, RT-QuIC is widely used for detecting prions in sporadic CJD patients’ cerebrospinal fluid [Orru 2015a], while PMCA can detect prions in variant CJD patients’ urine [Moda 2014]. The two assays have different limitations. For example, RT-QuIC does not amplify infectivity, so while it can produce large amounts of abnormal PrP, it is not clear whether/how these can be useful for structural studies. Both assays are generally used to read out a binary yes/no of whether any prions are present — as typically used, at least, they are not highly quantitative. And there has been only limited success in using these assays to discriminate different prion strains or subtypes [Orru 2015b]. Dr. Jackson has been using PMCA to generate synthetic prions (“SYPRIONS”) and then studying them by seeing how well they are able to infect cultured cells in the “scrapie cell assay” [Klohn 2003], by doing electron microscopy to examine their molecular structure, and using them to develop fluorescence-based assays for monitoring prions.

Gustavo Mostoslavsky: Modeling Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease using human iPSC-derived neurons

Dr. Mostoslavsky runs the Center for Regenerative Medicine at Boston University (BU), where he focuses on stem cell research. He has been collaborating with Alice Anane, founder and president of CJD Foundation Israel, and with BU prion researcher Dr. David Harris. Using cells with the E200K mutation donated by asymptomatic at-risk patients in Israel under a study that Alice Anane has organized, Dr. Mostoslavsky has been generating induced pluripotent stem cells and then differentating them into neurons in the lab using a protocol he has published [Park & Mostoslavsky 2018]. He has cell lines from ~20 individuals from a single family in Israel, some with and some without the mutation, including two individuals with the mutation who are still asymptomatic at ages 95 and 96. So far he has successfully reprogrammed some of these cell lines into neurons and has found that the neurons do produce PrP protein. His goal now is to characterize the effects of the E200K mutation on cells, and to develop a platform for screening potential therapeutic compounds.

Emmanuelle Vire: Investigating the relevance of blood DNA methylation signals for disease management in CJD

Dr. Vire was unable to attend the conference in person so she sent a video.

Layered on top of the sequence of A, C, G, and T letters that make up our genetic material, our DNA also contains a number of different chemical marks (“epigenetic” changes) that can play roles in how the DNA functions, which genes are turned on and off, and how cells differentiate into different types of tissues. One of those changes is methylation (the conversion of cytosine, or “C”, letters into 5-methylcytosine or “5mC”), which has been recognized for years but scientists are still understanding the important role it plays in regulating genes in health and disease [Razin & Riggs 1980, Schubeler 2015]. Dr. Vire is studying DNA methylation in the blood of prion disease patients. Her hope is that these studies could provide hints of new drug targets (proteins that could be targeted with therapies to fight the disease) or new biomarkers (genes or proteins that could be monitored in order to track disease progression or drug efficacy). So far she has collected blood from 112 sporadic CJD patients and 116 controls and has profiled DNA methylation in their genomes to see where the methylation changes are. She is also working on collecting blood samples from genetic prion disease patients, especially people who were monitored both before and after they became sick, in order to see whether there are differences in methylation before and after onset.

National Prion Disease Pathology Surveillance Center panel

Center Director Dr. Brian Appleby introduced the NPDPSC and its many activities. He showed videos of how the various cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) diagnostic tests — 14-3-3 Western blots, tau ELISA, and RT-QuIC — and analysis of autopsy tissue are performed at the center. He noted that the number of CSF samples referred for testing has grown over recent years, and is currently at about 4,000 per year, of which about 10% are deemed positive for prion disease. ABout 90% are sporadic, 10% are genetic, and in 2018 only 1 case was acquired (iatrogenic human growth hormone CJD). The number of autopsies requested is smaller and has actually declined, to about 400 per year, since 2015. He believes this is because RT-QuIC offers a sufficiently confident diagnosis that fewer physicians are recommending autopsy to their patients’ families. However, autopsy remains vitally important for confirming the diagnosis, and Dr. Appleby and CJD Foundation have been working on educating neurologists about this importance. As a result, the 2019 autopsy referral rate so far appears to be on the rise again.

The NPDPSC is funded out of the Congressional allocation to the CDC for prion surveillance. They requested $8 million for prion surveillance in the federal FY20 budget, and, despite threats of severe cuts, they are currently slotted in at $7 million in the House’s proposed version of the budget.

Dr. Appleby, Miriam Warren, Crissy Moskal, and Danielle Jordan then held a Q&A panel.

Q. What happens to patients’ samples after they are analyzed?

A. We do not throw samples out. They are kept for potential re-testing in case this is ever requested, and/or for research. The large bank of samples that the NPDPSC has accumulated is what has allowed them to do major research studies, for example confirming the accuracy of RT-QuIC diagnosis.

Q. Why does it sometimes take a long time to get RT-QuIC results back?

A. The test itself takes 60 hours, but the NPDPSC first has to receive the sample, which may spend a while in shipping. The NPDPSC is the only center in the U.S. that does clinical RT-QuIC testing, but some hospitals by default send all their samples to a single reference lab, which then has to re-package and send the sample to NPDPSC for RT-QuIC, causing further delays. Finally, the NPDPSC returns results to the referring physician, who may occasionally delay or forget to disclose the results to families for reasons that the NPDPSC has no control over.

Q. Why was it difficult to arrange funeral services for my loved one?

A. It shouldn’t be, and NPDPSC and CJD Foundation have been working on educating funeral home directors about the fact that it is possible to safely manage funeral preparations for people who died of prion disease and that people should not be refused funeral services. There was an article to that effect earlier this year in the National Funeral Directors’ Association (NFDA) publication The Director, and there are ongoing workshops and outreach efforts.

Q. Is it possible to get my loved one’s diagnostic test results?

A. NPDPSC, like any other lab, is not allowed to directly return results to patients. Cerebrospinal fluid test reports can only be sent to the referring physician. If your physician is not returning results in a timely or competent fashion, you can change providers and reports can be re-sent out. This is true even of autopsy results: if you are the legal next of kin you can go to a different physician and they can get NPDPSC to release the autopsy results to them.

Q. Is the NPDPSC analyzing autopsy tissues other than brain?

A. Where families are willing to donate these tissues, skin and eyes have been analyzed for presence of abnormal PrP. In people who ate venison and lived in states where deer/elk are known to have chronic wasting disease, NPDPSC is also asking for spleen and lymph nodes to be donated. Although there is no evidence that chronic wasting disease has ever been transmitted to humans, we know that in the cases where humans acquired variant CJD from “mad cow” or BSE-infected meat, the abnormal PrP accumulated in their spleen and lymph nodes before entering the brain, so NPDPSC wants to keep monitoring these tissues so that if chronic wasting disease ever does turn out to transmit to humans, this risk will be detected sooner rather than later. That said, NPDPSC is careful to try not to ask families for too much, as it is such a difficult time and they don’t want the bereaved to be overwhelmed with requests.

Ryan Maddox: CDC report

CDC undertakes a variety of activities to monitor prion disease, including both analysis of human data as well as monitoring the threat of chronic wasting disease. CDC integrates data from NPDPSC’s autopsy program as well as from analysis of death certificates. In 2016, the last year for which data are complete, there were a total of just over 500 prion disease deaths in the U.S. A total of 5,737 people are known to have died of prion disease from 2003-2016 inclusive. This corresponds to about 1 in every 6,000 deaths, meaning that the average person on the street has a 1 in 6,000 lifetime risk of dying of prion disease. If you frame it in terms of annual incidence (cases per year) instead of lifetime risk, then the numbers sound much lower — the average annual age-adjusted incidence was 1.3/million/year in men, and 1.1/million/year in women. (How common a disease is can be measured in many different ways, and this often leads to misperceptions — see this blog post.) Only 12 cases in this time period died before the age of 30, for a annual incidence of 6.9 per billion in this age group.

There is currently no evidence that sporadic or genetic prion disease can be transmitted through blood, although there are a small number of cases where variant CJD has transmitted through blood transfusions [Hewitt 2006, Davidson 2014]. Variant CJD is the term for prion disease acquired from BSE or “mad cow” disease. To date there have been 231 cases worldwide, mostly in the U.K.; there have been 4 cases in the U.S. and 2 in Canada, but none are believed to have acquired the disease in North America. FDA does not regulate organ donation, and there are no absolute exclusions.

There is currently no evidence that chronic wasting disease has transmitted to humans. Certain laboratory studies that have suggested the potential exists, and the history of “mad cow” / BSE urges proactive caution and surveillance. CDC undertakes several programs to monitor the threat of CWD to humans, including a program to follow hunters in Wisconsin who consumed venison from CWD-infected deer, and a program to follow up on prion disease cases in Wyoming and Colorado where the disease is endemic.

In Q&A, one audience member asked about clusters where several prion disease were all observed in a small region in a short period of time, or where two family members died of sporadic prion disease. Dr. Maddox said CDC has investigated several clusters in the past. In a country as large as the U.S., clusters will sometimes genuinely occur just by chance. In other cases, when CDC has investigated the cluster closely, it wasn’t actually a cluster, for example, not all the cases were truly prion disease, or the hospital where they were identified serves really large enough population so that the number of cases is actually consistent with expectation. There is no evidence that prion disease is transmitted between people, and so far no “cluster” has shown any evidence of being due to an infection event. (Again, see this post for some numbers on why things that seem like unlikely coincidences are actually expected.)

Steven E. Arnold: Assessing long-term stability of cerebrospinal fluid PrP levels in genetic prion disease mutation carriers

While the specific goal of this Research Grant was to assess long-term stability of PrP in cerebrospinal fluid, the overarching goal of Dr. Arnold’s study is really to prepare for prevention and treatment studies. This work is motivated in large part by the ongoing development of antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) as therapies for prion disease. The way ASOs work is that they attack the RNA molecule for one specific gene, in this case the prion protein gene, reducing the amount of protein produced from that gene. By lowering the amount of normal PrP produced, we can lower the amount of misfolded PrP produced or delay the time when PrP starts to misfold or slow the rate at which it misfolds.

Planning for success and assuming we soon have an ASO drug candidate ready to enter clinical trials, we have to ask the question: how will we know if an ASO is working? In symptomatic patients there are various clinical outcomes we can measure, such as survival, rate of disease progression and so on. In both sympomatic patients and presymptomatic individuals at risk, we can also measure biomarkers — molecular measurements that tell us whether the drug is working. The goal of this study is to establish these sorts of biomarkers in presymptomatic people at risk for genetic prion disease.

The clinical research study Dr. Arnold runs at Mass General Hospital has so far seen 43 individuals. Participants are invited to make two initial visits to the clinic, about 8 weeks apart. After that, thanks to the grant from CJD Foundation, they are being invited to come back after another year. This sequence of visits allows us to assess biomarker stability or potential changes over both the short term and the slightly longer term. In terms of demographics (age, sex, and education), basic health assessments, and measures of cognition, anxiety/depression, and so on, mutation carriers are similar to controls.

The most important part of the study is testing of spinal fluid, which is produced deep within the brain and flows around the brain and spinal cord and can be accessed through a needle inserted into the base of the spine. The primary goal of the study is to figure out whether the amount of PrP in spinal fluid is stable over time for each person. If PrP concentration varies wildly from day to day within the same person, then it would be really hard, in a clinical trial, to measure whether an ASO lowered that concentration of PrP. But if PrP is stable, then we should be able to easily measure the effect of an ASO. Thankfully, the answer so far is that PrP level is very stable within one individual over both the short term and the long term. This means that if we are able to give an ASO to presymptomatic mutation carriers to lower PrP, we should be able to measure the effect of that drug candidate using this biomarker. Dr. Arnold and we (Sonia and Eric) are working with scientists at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to develop this biomarker as an outcome measure for clinical trials.

In addition to measuring PrP levels, the study is also looking in spinal fluid for potential early markers of the disease process, such as the neuronal damage markers tau and neurofilament light (NfL). So far, mutation carriers look similar to controls. In general, we cannot detect any evidence that these mutation carriers are in “prodromal” state where a silent disease process has begun — instead, their brains seem to be healthy. The study is ongoing and we hope that more people will participate and that we will have more research updates to share in the near future.

Roberto Chiesa: Nanoparticle-mediated brain delivery of a tetracationic porphyrin with potent anti-prion activities

Dr. Chiesa provided an update on his project, first presented at this conference in 2016, to develop a compound that binds PrP and lowers the amount of PrP on the cell. His molecule is named Zn-VA01 and it is a zinc porphyrin. This idea began with Byron Caughey’s work 20 years ago showing that a class of molecules called porphyrins could bind PrP and slow down the formation of misfolded PrP [Caughey 1998]. Dr. Caughey studied, among other things, an iron porphyrin, which Dr. Chiesa uses as a comparator his studies of his new zinc porphyrin. Zn-VA01 is efficient at inhibiting prions in prion-infected mouse cells grown in the lab (its half maximal effective concentration was 0.58 μM, and at concentrations closer to 5 μM it completely cured the cells of infection). It was similarly effective in cerebellar organotypic cultured slices (COCS), which are a form of “primary culture” made from fresh brain tissue from mice.

The big challenge with porphyrins is that they are relatively large molecules, which may keep them from diffusing into the brain if given intravenously. To assess this, Dr. Chiesa undertook pharmacokinetic studies, where they dosed mice with Zn-VA01 and then did serial measurements of the concentration in the blood and in the brain. After a single dose, the compound only got up to about a concentration of 200 ng/g in brain tissue, which is much lower than in blood plasma, not high enough to have a therapeutic effect. The compound was surprisingly stable in the brain, though, so they also tried a chronic dosing study. In this study, after repated dosing (at a 10 mg/kg intraperitoneal dose) they were able to get the brain concentration up to about 1,000 ng/g, which is close to the effective anti-prion concentration of the compound, but still not quite there.

In light of these challenges, Dr. Chiesa set out to develop an enhanced delivery method for getting this compound into the brain. He focused in on g7-nanoparticles, which use a synthetic peptide that binds the opioid receptor (but does not have opioid-like effects) in order to get into the brain [Costantino 2005]. These particles have been used to deliver candidate therapeutic molecules to the brain in mouse models of Huntington’s and other neurodegenerative diseases. So far, Dr. Chiesa has found that these nanoparticles result in efficient uptake into COCS, with the anti-prion properties of the porphyrin maintained upon this route of delivery. He is beginning studies in live mice to see if these nanoparticles will give good enough brain uptake to test whether the compound is effective in the brain.

Jiyan Ma: Determining the therapeutic potential of an anti-PrP nanobody

Dr. Ma began with an introduction to prion “strains”. There is more than one way PrP can misfold — it can adopt many different bad shapes, each of which is capable of forcing other copies of PrP to adopt its own shape. These various different shapes, or conformations, of PrP, can cause slightly different subtypes of prion disease. One proposed therapeutic approach in prion disease is to attack the misfolded form of PrP, but researchers who pursued this approach have found molecules that work against one prion “strain” but not another — in fact, the compounds they have found that are very effective against mouse prions, don’t work against human prions at all [Berry 2013]. Another proposed therapeutic approach is to try to defend cells against the neurotoxicity of prions. A challenge here is that we have not yet identified any really good drug targets for neurotoxicity — for example, one study tried going after a protein called PERK, but that protein is really important in the pancreas, and so it had severe toxicity problems in the mice [Moreno 2013]. A third strategy is to go after PrP in its normal form, which has been pursued with antisense oligonucleotides and with monoclonal antibodies, with some success. Therefore Dr. Ma is interested in targeting normal PrP.

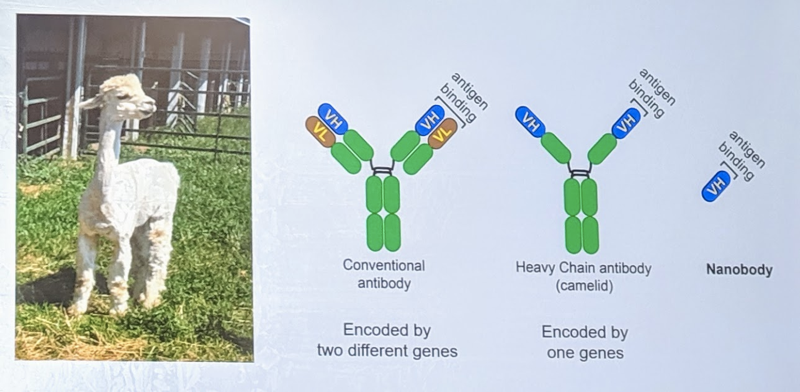

How to target normal PrP? One strategy is with antibodies, but antibodies are large and difficult to get into the brain. Dr. Ma therefore became interested in “nanobodies”, which are the protein-binding part of the antibodies produced by sharks, llamas, and alpacas. Nanobodies are much smaller (~15kDa) than, say, human or mouse antibodies. In fact, one study has already shown that nanobodies that bind PrP can inhibit prion formation in vitro [Abskharon 2014]. Dr. Ma was interested in testing whether they work in vivo in live mice.

Dr. Ma produced and tested 25 different nanobodies against PrP in alpacas in Michigan and identified nanobodies that inhibit prion replication in vitro. He is putting the DNA encoding the nanobodies into an adeno-associated virus (AAV), which is a type of viral vector used for gene therapy. The plan now is to inject mice with an AAV that will cause them to produce these nanobodies in the brain so that the nanobodies can bind PrP without needing to cross the blood brain barrier and without the mice needing to be injected with the nanobodies themselves.

Patrick Cauntay: Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) and engaging with patient families

Dr. Cauntay began his career as a scientist in Ionis Pharmaceuticals’s toxicology group and more recently transitioned to the company’s patient advocacy group, which he represents today. He began by thanking everyone at the conference for allowing him to come and learn more about the patient experience in prion disease. His goal is to partner with patients, and learn from them to inform research, development, and clinical strategy for developing a drug.

Ionis was founded in 1989 to develop a new platform for drug discovery based on RNA-targeting therapeutics. The company today has about 500 employees, with 3 approved drugs including, most recently, nusinersen for spinal muscular atrophy. They have a growing pipeline of over 40 potential medicines in development. Their drugs and drug candidates have been in over 100 clinical studies, with over 6,000 patients dosed in these studies. ASOs do not cross the blood brain barrier, so ASOs for neurological indications have to be delivered directly into spinal fluid (intrathecally or “IT”). Nusinersen, their drug for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is delivered this way. Nusinersen is the first treamtent for all forms of SMA. It is approved in 40 countries, with formal reimbursement in 30 countries, and over 7,500 patients on drug today.

Ionis’s usual pipeline is to identify a drug target, develop molecules capable of binding the RNA for that target, testing them in cell lines, then testing them in animals, then finally advancing to human trials. Their ASO program for prion disease is currently in the animal testing phase. While they are working on developing the drug in the lab, they also have a long to do list including to better understand the disease, work with clinicians and researchers to characterize all forms of prion disease, and work with patients to understand their experience and their hopes for a treatment.