Fluphenazine, trimipramine and two styryl compounds

Read with caution! This post was written during early stages of trying to understand a complex scientific problem, and we didn't get everything right. The original author no longer endorses the content of this post. It is being left online for historical reasons, but read at your own risk. |

Chung 2011, of the Wisniewski lab at NYU, tested four compounds in prion-infected mice and found significant (~20%) delays in disease onset for all four. I’ve mentioned this study in a previous post, but gave it a more thorough read today.

The story starts with two classes of compounds believed to have antiprion properties: tricyclics and styryl-based compounds. Quinacrine is a tricyclic, and as discussed in the quinacrine post, the best evidence does suggest that quinacrine has antiprion properties in vitro; its lack of in vivo efficacy might be due to pharmacokinetics (it accumulates in lysosomes) or because not all prion conformations respond to it, resulting in a “resistant” population. So there is a possibility that another tricyclic could do better. Chlorpromazine, another once-promising antiprion compound, belongs to phenothiazines, a subset of tricyclics. Styryl compounds also have a strong (more recent) history in prion disease research: Wisniewski’s group had also screened tens of styryl compounds for imaging purposes a few years earlier [Li 2007], and the Doh-Ura group has investigated their use both for imaging of amyloid plaques [Ishikawa 2006] and as prion therapeutics (see cpd-B).

So both of these classes of compounds were strong candidates for potential prion therapeutics. Chung et al screened the Li 2007 list of styryl compounds, along with two FDA-approved tricyclics, trimipramine and fluphenazine (the latter a phenothiazole like chlorpromazine). The screen used an in vitro model of N2a mouse neuroblastoma cells infected with 22L brain homogenate. The readout of this screen was the same standard practice as used in the recent UCSF ELISA assay: digest with proteinase K and then Western blot for PrP. Any PrP remaining after proteinase K digestion is considered to be PrPres and thus taken to be toxic/infectious. They also screened for cytotoxicity. Trimipramine, fluphenazine and two styryl compounds, referred to as #23I and #59, won the game of having both antiprion properties and low toxicity.

All four of these molecules then advanced to the in vivo stage of the study. The in vivo model consisted of wild-type mice injected peritoneally with 100μL of 1% 139A brain homogenate. The treatment group mice received intraperitoneal injections of the candidate therapeutics 5x/week, beginning immediately, continuing for 1 month (in the case of #23I and #59) or until sacrifice. They started with 25 control mice and 25 per compound, but sacrificed 10 per group early on to examine their spleens; the delay-in-onset conclusions of the study are based on 15 mice per group.

The results are pretty impressive:

| Compound | Dose | Average survival | %change vs. control | n |

| Control | N/A | 170 days | N/A | 15 |

| Fluphenazine | 1 mg/kg | 205 days | +21% | 15 |

| Trimipramine | 10 mg/kg | 210 days | +24% | 15 |

| #23I | 10 mg/kg | 202 days | +19% | 15 |

| #59 | 10 mg/kg | 215 days | +26% | 15 |

Each mouse was sacrificed when and only when a blinded observer had noted ataxia for three consecutive weeks. So although the results are presented in terms of survival time, in practice they represent time of disease onset. These delays in onset are larger than those seen for rapamycin, statins or in most studies of tetracyclines. All the results were statistically significant at p = .0005 or better.

We don’t know much about the two new styryl compounds #23I and #59 — presumably no humans have taken them before, and Chung does not give molecular diagrams. But let’s get to know the two FDA-approved drugs in this study a bit better:

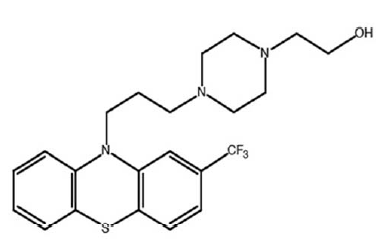

Fluphenazine

Fluphenazine (above) is scary stuff. It’s a typical antipsychotic, which means it’s a dopamine antagonist and has side effects on the extrapyramidal system (the system controlling involuntary movements). To this day I am haunted by the memory of, years ago, my professor in undergraduate neurobiology describing how some drugs prescribed to schizophrenics cause tardive dyskinesia — your face contorting in horrible expressions against your will — which is in many cases irreversible. Fluphenazine is one of those drugs. According to Medscape some 60% of people who take fluphenazine get akathisia (inability to stay still). The list of drug interactions weighs in at over 10% of all FDA-approved drugs.

Is all this worse than prion disease? Of course not. But other things being equal, I would certainly be inclined to prioritize further work on more benign molecules.

The dose of fluphenazine, 1 mg/kg 5x/week, works out to about 4 mg/day for a 70 kg person (using body surface area conversion, 1*3/37*5/7*70 = 4), which is within the range used clinically. It used to be a Bristol-Myers Squibb molecule but long since went generic.

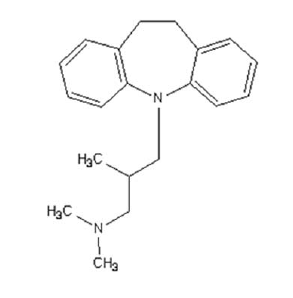

Trimipramine

Trimipramine (above) is a tricyclic (note the two benzenes and then the heptagonal ring between them). A number of different drugs are tricyclics, but trimipramine belongs specifically to tricyclic antidepressants, which are old-school drugs which have been largely phased out clinically in favor of SSRIs (Prozac and all its prodigy). While trimipramine does actually inhibit uptake of serotonin (and norepinephrine), its main mechanism of action (as an antidepressant) is believed to be that it’s an antagonist for several different, mostly excitatory, neurotransmitter receptors — especially for the H1 histamine receptor. This causes drowsiness and is precisely the mechanism of action of Benadryl (Almost. Benadryl, an antihistamine, is actually an inverse agonist for H1, which means it’s a more-than-antagonist. The drowsiness isn’t actually an off-target effect — it’s a direct consequence of the intended action of Benadryl on H1). Similarly, trimipramine can be used to treat anxiety and insomnia. You’re cautioned against driving after you take it [Medscape].

So if it is an antiprion compound, it’s got its share of side effects and interactions but, on the whole, seems more benign than fluphenazine. The dose used, 10mg/kg, works out to ~40 mg/day for a 70 kg person (based on 10*5/7*3/37*70), is even a bit on the low side: doses for depression start at about 50 mg.