Anti-PrP vaccines

Read with caution! This post was written during early stages of trying to understand a complex scientific problem, and we didn't get everything right. The original author no longer endorses the content of this post. It is being left online for historical reasons, but read at your own risk. |

For the past ten years, a few scientists, led chiefly by Dr. Thomas Wisniewski of NYU, have been working to develop a vaccine against prion infection. As the group points out in one of its papers, “the creation of vaccines is one of the greatest successes of medical and veterinary science”– so why not apply this approach to fighting prions?

Traditionally, a vaccine would consist of an inactivated or less virulent version of a pathogen which allows your body to “learn” how to fight the real live pathogen. What that means at the molecular level is that the vaccine preparation contains the same surface protein(s)—or at least, surface proteins with the same epitope—as the true pathogen, so that your B cells can develop a immunoglobulin (Ig), aka antibodies, with the paratope to the true pathogen’s epitope. To “discover” the right paratope against an antigen, the immune system uses its own form of high-throughput screening: the paratope of immunoglobulin is a mutation hotspot in genomic DNA, so when immune cells proliferate, they produce a huge number of different peptide sequences in that crucial region. After the infection is beaten back, the B cells with the winning paratope can stick around as memory B cells and produce the antibody for years or decades in case you get infected again. A booster shot may help them stick around longer.

As a target for a vaccine, though, PrP is a bit unusual. Here are three obvious concerns:

- It’s a “self antigen” in immunologist’s parlance, or a “host encoded protein” in molecular biologist speak. It’s your own protein, so how can you get the immune system to recognize it as an invader?

- And even if you could, wouldn’t that be bad? When your immune system develops antibodies against one of your own proteins that can lead it to attack and kill your own cells. That’s called autoimmunity and is the cause of syndromes as varied as vitiligo and type 1 diabetes.

- Will the antibodies be specific to a disease allele or conformation, or will they target and deplete you of healthy PrP? And if so, what are the the consequences of that?

- Yes, PrP is a self antigen and most of the difficult science that’s gone into developing the vaccines is focused on this question, of how to get the host to launch an immune response to a self antigen.

- Autoimmunity is potentially an issue, but empirically, the studies in mice so far have not shown any adverse effects, so for whatever reason, vaccines tested so far do not seem to be leading the immune system to attack host cells.

- No one has yet managed to create an antibody specific to misfolded PrP or allele-specific for a disease-causing allele. The use of a vaccine that induces you to create non-allele-specific or non-conformation-specific anti-PrP antibodies, so the effect of the vaccine would amount to a knockdown of PrP, at least in the tissues where the antibodies end up localizing. The notion that such a knockdown might be okay rests on the assumption that you can live without PrP, as suggested by the viability of PrP knockout mice [Manson 1994].

| vaccination time | anti-recPrP titer before infection | 139A brain homogenate dilution | days to sacrifice | control | difference | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| prophylactic | high (avg 20135) | 1:10 | 189±4 | 173±2 | +9% | .002 |

| prophylactic | low (avg 9645) | 1:1000 | 205±3 | 197±3 | +4% | .04 |

| rescue | all | 1:10 | 192±5 | 190±5 | N/A | ns |

| rescue | all | 1:1000 | 222±4 | 210±3 | +6% | .018 |

So the immunization did something. For three of the comparison groups, the effect sizes were small but statistically significant. The authors also noted that within some of the groups, the anti-recPrP antibody titer correlated significantly with age of disease onset.

This study showed that an immune response against PrP was possible and (at least in an intraperitoneally infected model) beneficial. The question was how to get a stronger response.

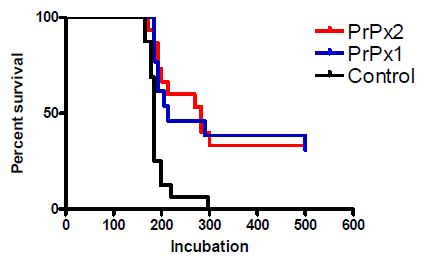

Looking at that graph, you’ll notice that some of the mice got sick and died just about as soon as the control mice did; the significant difference is really driven by the ~30% of mice that just never got sick.

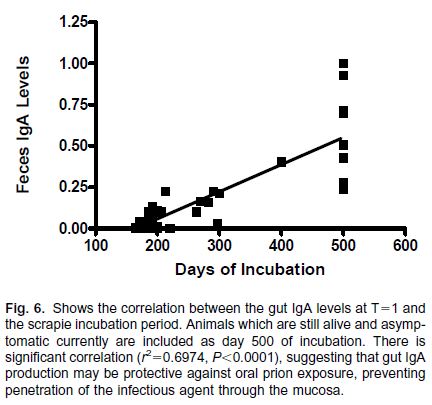

The researchers measured IgA and IgG levels in the mice. IgA, a mucosal antibody, represents about 75% of all immunoglobulins in the body and is localized in large part to the digestive tract. IgG is more of a systemic antibody, found in the serum and thus throughout the body. The Salmonella-based vaccine was targeted specifically at mucosal immunity, but nonetheless, the researchers found significantly higher-than-control levels of anti-PrP IgA and IgG in the vaccinated mice after the vaccination course (Figs 4 & 5). (Interestingly, when tested again after the infection, the non-vaccinated mice also had some level of these antibodies, indicating there is at least some degree of immune response to oral prion infection itself).

And, just as Sigurdsson 2002 had observed, the titer of anti-PrP antibodies was significantly correlated with the mice’s survival:

(Fig 6 above measures IgA levels in feces. IgG levels in blood plasma were also correlated with survival, R2 = .62, p = .001, but the IgA and IgG levels were significantly correlated with each other, R2 = .36, p = .001)

So again, it looked like the anti-PrP antibodies were highly effective at fighting off prion infection, the question was one of making the vaccine effective at inducing production of anti-PrP antibodies.

The group’s next (and to date latest) publication on on prion vaccines [Goni 2008] took a more aggressive vaccination protocol. The PrPx2 Salmonella vaccine was administered to mice orally four times with live Salmonella and then twice more with dead Salmonella as a booster. Then before infection with scrapie the mice were divided into four groups according to how they responded to the vaccine: all permutations of high vs. low IgA and IgG levels, with 10 – 14 mice per group. They compared these mice to two control groups: mice not vaccinated, and mice that were “vaccinated” with Salmonella modified with an empty vector with no PrP. The control groups were not significantly different in survival so they were combined into one control group with n = 20.

Here are the results:

| group | survival at 400 days | n | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High IgA / High IgG | 100% | 14 | .0001 | |

| Low IgA / High IgG | 33% | 12 | .02 | |

| High IgA / Low IgG | 0%; median survival 198 days vs. 194 controls | 10 | ns | |

| Low IgA / Low IgG | 0% | ns |

Post-mortem histology showed no evidence of autoimmunity: “there were no signs of organ inflammation or other toxicity that could be associated with vaccination or autoimmunity evident by histological analysis (data not shown)”.

This work shows that anti-PrP vaccination can bring about complete abrogation of prion infection in mice, as long as the animals respond to vaccination by creating enough antibodies.

It is interesting that IgA and IgG appear to both play a role in the immune response to the Wisniewski lab’s vaccines. When you first hear of the idea of an anti-prion vaccine, you might imagine that this would be a mucosal vaccine bringing about mucosal immunity, where only IgA is important and it works by targeting ingested PrP and/or depleting your gut of PrP so that prion infection cannot take hold. Such a vaccine would be expected to only work against oral routes of prion infection (e.g. BSE, CWD) and not against sporadic or genetic forms of prion disease.

But the Wisniewski group’s results suggest the possibility that some degree of humoral—i.e. systemic, throughout bodily fluids—immunity can be attained and can be helpful in fighting off prion infection. At first glance this seems unlikely: will antibodies really get into the brain, and if they do, will they be so well-behaved as to target misfolded proteins but not kill the neurons that produce them? Yet this is the whole premise on which Alzheimer’s vaccines are based. Immunotherapy for Alzheimer’s has been an active area of research for over a decade (for a review see Wisniewski 2008), with one anti-Aβ vaccine, AN1792, having made it to Phase II clinical trials. AN1792 showed modest cognitive improvements and large reductions in Aβ deposits but the trial was discontinued due to an adverse reaction in 6% of patients, who developed meningoencephalitis (inflammation of the meninges and brain, presumably due to an autoimmune reaction).

To be sure, the Wisniewski group are not the only ones working on immunotherapies for prion disease, and there is considerable debate over the potential for therapeutic value versus autoimmune toxicity and what is the right approach to take. Heppner 2001 showed some success with mice expressing transgenic anti-PrP antibodies, presumably suggesting the possibility of passive immunization (i.e. providing the antibodies directly rather than vaccination to induce antibody production). But Lefebvre-Roque 2007 reports a severe toxic reaction to passive immunization in mice, and Donofrio 2005 discusses the neurotoxic properties of cross-linking PrPC by bivalent antibodies. Collinge has been a proponent of an immunotherapy approach to prion diseases, and such is listed as a major research area of the MRC Prion Unit, though the approach has not always been successful (no delay in scrapie onset after vaccination in Tayebi 2008). For a bit more discussion see Aguzzi 2004 under “Immunotherapy for prions?” and reviews by Wisniewski & Goni 2010 and Wisniewski & Goni 2012.

While the science is far from perfected at this point, it now looks conceivable that vaccines could actually induce the immune system to fight off host-encoded proteins such as PrP in the brain and thus be effective even in sporadic or genetic forms of prion disease. While not all mice in the Goni 2008 study showed a strong vaccine response, the complete protection against prion disease among mice that did have a strong response points to the therapeutic potential of vaccination and the merits of testing this approach in other mouse models of prion disease.