Genetics 18: 'Modifier and mosaic screens in Drosophila'

These are my notes from lecture 18 of Harvard’s Genetics 201 course, delivered by Mitzi Kuroda on October 31, 2014.

A note on transgenesis

In Drosophila, if you are testing whether a wild-type transgene can rescue a mutant, you usually want to bring it in on another chromosome. Thus you are comparing, for instance, mut1/mut1; +/+ vs. mut1/mut1; {transgene, GFP+}/+.

Tissue-specific analysis

Drosophila only have 13,000 genes. The ones that are essential are often essential in many different pathways. A challenge is how to identify genes that are required in specific cells, regardless of their other functions in other cells.

Today we’ll discuss two ways of doing tissue-specific analysis, both of which are F1 screens and enable screening >100,000 flies.

- Modifier screen

- Clonal or mosaic analysis

Modifier screen

For modifier screens, you want to start with a genotype that has a “borderline” or “sensitized” phenotype - for instance, a partial loss of function - where it is of moderate severity such that you can screen for enhancer mutations that make it more severe, and suppressor mutations that make it less severe. The screen involves looking at F1s after mutagenesis, so they are all heterozygous for any new mutations. Thus you can only find dominant suppressors and dominant enhancers.

As an example, consider the white gene, which makes eyes red (loss-of-function mutants have white eyes). We’ll discuss the “white mottled four” or wM4 hypomorphic chromosome, in which a wild-type copy of white+, which is normally located in the X chromosome telomere, has been translocated into centromeric heterochromatin, resulting in silencing of the gene in most but not all cells. This results in “variegated” eyes that have patches of white and red. This is an example of a genotype with a “borderline” phenotype. (FYI: This experimental system is revisited, complete with a diagram, in Fred Winston’s epigenetics lecture).

For this screen, you take homozygous wM4/wM4 males and females, mutagenize the males, then cross. Many F1s will simply have a wM4/wM4 genotype with no interesting de novo mutations. However a subset will have either an enhancer of variegation wM4/wM4; E(var)/+ or a suppressor of variegation wM4/wM4; Su(var)/+.

This screen revealed that enhancers of variegation typically were mutations resulting in a 50% reduction in factors that positively regulate transcription, and suppressors of variegation typically were mutations that caused a 50% reduction in heterochromatin components. For example, Su(var)205 proved to be a mutation in HP1, a key conserved heterochromatin protein.

Many of the suppressors are mutations in haplosufficient genes, such that a +/+; Su(var)/+ fly has no phenotype. This is why you can only find these mutations in the context of another “borderline” / “sensitized” phenotype.

Clonal or mosaic analysis

Clonal or mosaic analysis allows homozygous loss-of-function to be assayed in a heterozygous animal. You work with a mut1/+ het animal in which you’ve been able to construct a clonal patch of tissue in which the mutation has been homozygosed.

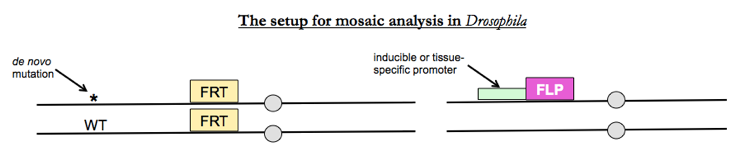

Mutagenize fathers and perform a cross to create F1s which have the following genotype:

- Either tissue-specific or heat shock-inducible expression of the yeast enzyme FLP recombinase (pronounced “flip”)

- Homozygosity for a FLP recombination site, which is called FRT

- A heterozygous mutation on the same chromosome arm as the FRT site

Flies normally have recombination only during meiosis. FLP recombinase allows you to induce recombination during mitosis.

Whereever FLP recombinase causes mitotic recombination, you’ll get half +/+ cells and half wt/wt cells.

One popular use of this technique is to find growth control genes by looking for mutations that, when homozygosed in a given tissue, cause that tissue to overgrow. This led to discovery of the hippo pathway. This wouldn’t have been possible without mosaic analysis because homozygosity for hippo mutations in the whole body is embryonic lethal.

The utility of mosaic analysis is not limited to random mutagensis screens. Being able to control gene expression or mutation zygosity in a tissue-specific manner is a useful technique for examining your favorite gene. There are many tools available on Flybase.org for these sorts of experments, including all the heat shock-inducible and tissue-specific FLP transgenes you might want, and FRT sites on either arm of any chromosome.

Now, the hippo pathway mutants had the benefit of causing overgrowth, which is easy to see. How do you study mutations that result in slower growth and get outcompeted by wild-type cells? A solution is to add a GMR-hid transgene on the same chromosome arm as the FRT site. GMR is an eye-specific promoter and hid causes cell death. The transgene is dominant, so any fly that has this transgene has no eyes (which is viable). You put your mutation of interest (call it mut1) on the same chromosome arm but in trans to GMR-hid. Now the resulting flies will have no eyes, unless you induce FLP recombinase in which case you will get 50% of cells that are homozygous GMR-hid and 50% that are homozygous mut1/mut1. As a result, all of the eye tissue will be mut1/mut1. Thus even if the mutation causes slow growth it will fill the eye compartment and you can examine it.

Note from Q&A: the Cre-lox system does work in flies but is not as often used as the FLP recombinase system.

MARCM

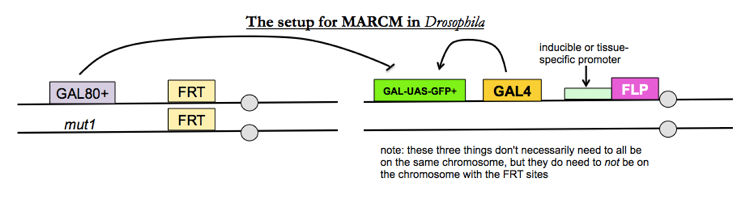

If you want to look at internal tissues or even single cells, you want a method called mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker (MARCM), which is a specific variation on mosaic analysis. The goal is to have flies where any cell with your mutation heterozygous is GFP-, and any cell with the mutation homzoygous is GFP+.

- GAL4 is a transcriptional activator which flies do not have endogenously, yet which works very well in flies.

- GAL-UAS-GFP+ is a GFP transgene given by a GAL4-dependent promoter

- GAL80 represses transcription of the GAL-UAS-GFP+ transgene

Therefore, only in cells where FLP recombinase has homozygosed your mutation of interest, thus necessarily removing the GAL80+ transgene, you will see GFP expression.

GAL-UAS is a popular system in Drosophila and many reagents are available - for instance, GAL-UAS constructs for your favorite gene, or GAL-UAS-driven shRNAs against your favorite gene, or special FLP constructs that loop out and delete one region of a chromosome instead of inducing recombination between chromosomes. This last type of construct serves a purpose similar to Cre-lox.

Mini-survey of behavioral genetics in Drosophila

All of these tissue- and cell-specific techniques introduced above have been useful for figuring out which neurons are responsible for which behaviors in Drosophila. Most individual tissue-specific regulatory elements function in many cells, which isn’t specific enough for studying one or a handful of neurons. However, if you require the intersection of two different regulatory elements, you can get down to one or a few cells. You can use UAS-GFP transgenes for mapping neurons, UAS-TrpA (a channel that activates neurons) for studying activation of neurons, and UAS-TNT (a toxin that blocks activation) to study inhibition of neurons.

This technique has been used to find neurons whose activation (with UAS-TrpA) causes flies to moonwalk: