How do SOD1 mutations cause ALS?

I am continuing to work on my final project for my protein folding class on the mechanism by which SOD1 mutations cause ALS. After getting acquainted with some basic background, this second post on the subject, meandering through a few different aspects of the protein and the disease. Bear in mind that I’m an outsider here - I study PrP, not SOD1 - so I might be totally off base on any of this. If I am, please feel free to leave me a comment below!

SOD1 before SOD1 ALS

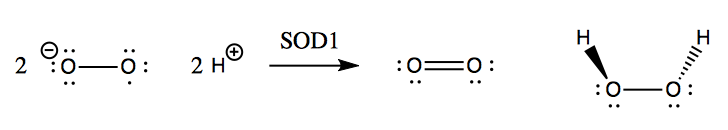

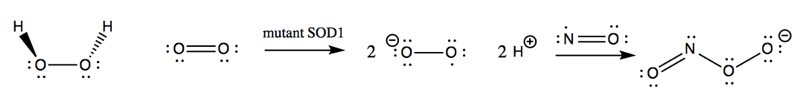

SOD1 was well-known as an enzyme long before it was ever linked to a genetic form of ALS. Its native function is to catalyze the reduction of superoxide (O2-) with ambient protons to yield O2 and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2):

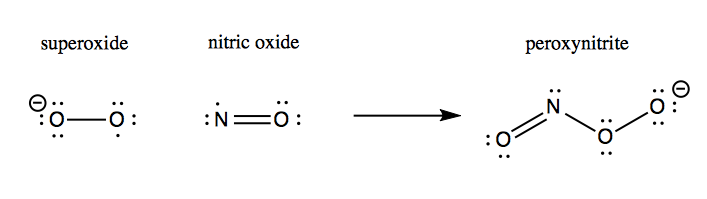

Although hydrogen peroxide is still a fairly reactive substance, it is less reactive than superoxide, and so this conversion apparently helps save the cell from much oxidative damage. Left to its own devices, superoxide will react with nitric oxide to yield peroxynitrite, which damages proteins:

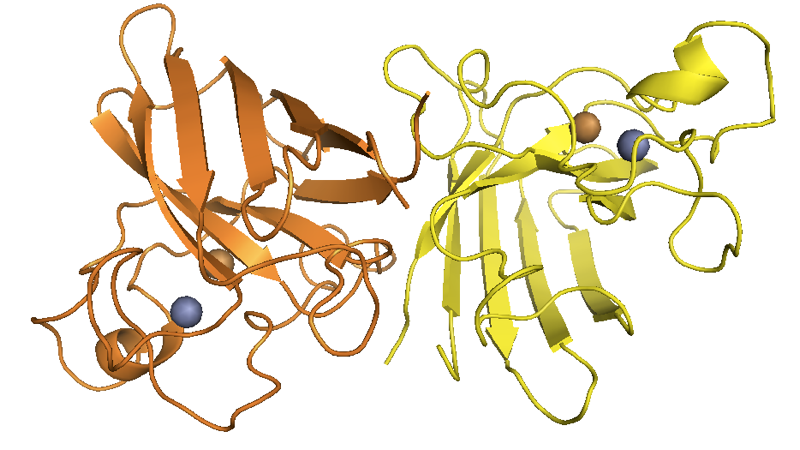

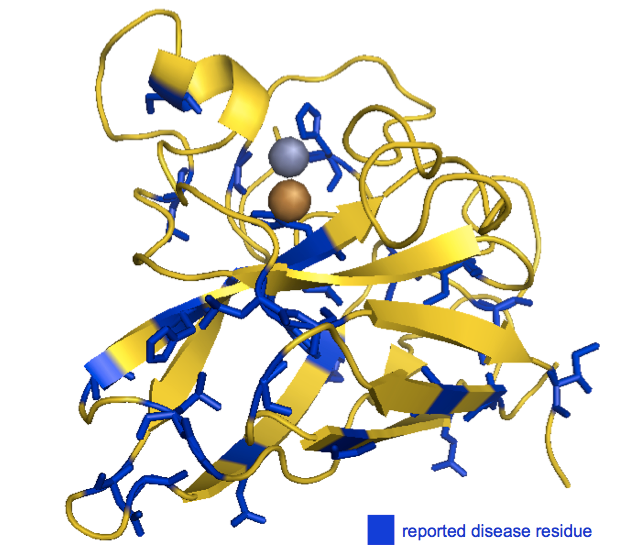

SOD1 in its native fold is a homodimer of 8-stranded Greek key beta barrels, with the catalytic site located at the hairpin turns and loaded with Cu2+ and Zn2+ ions:

Above: from this post.

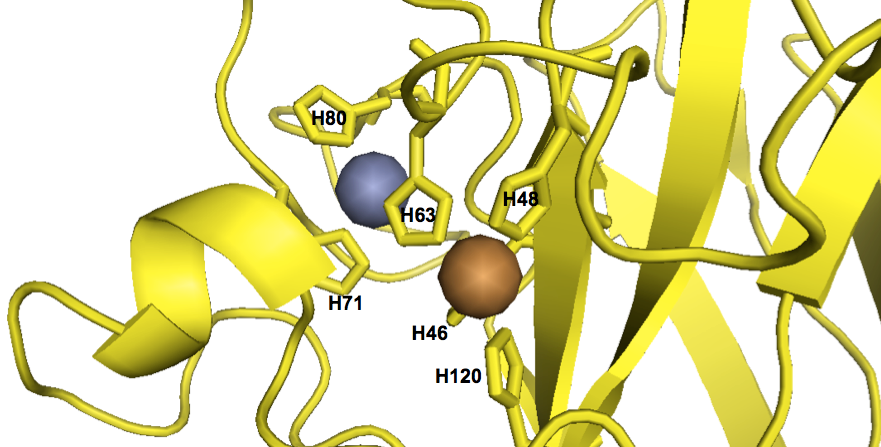

As far as I can tell from staring at the structure, the metal ions at the catalytic site are coordinated by a total of six histidines:

fetch 1sos

bg_color white

hide everything

color 0xFFD700, chain A

show cartoon, chain A

show sticks, chain A and (resi 46+48+63+71+80+120)

show spheres, inorganic and chain A

color 0xC77F33, chain A and element Cu

color 0x7C7FAF, chain A and element Zn

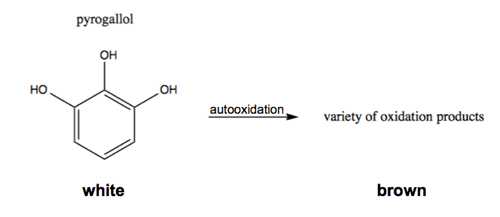

There are simple colorimetric assays for the enzymatic activity of SOD1. For instance, pyrogallol is a white substance which will autooxidize to form a variety of brown oxidized products:

This relies on superoxide as an intermediate, so adding SOD1 will reduce the white-to-brown color change [Marklund & Marklund 1974].

Linkage of the SOD1 gene to ALS

Genetic forms of ALS had long been recognized [Mulder 1986]. One form of dominantly inherited ALS was eventually linked to chr21 [Siddique 1991], and eventually turned out to be caused by a variety of missense mutations in the SOD1 gene [Rosen 1993, Deng 1993].

It is worth reflecting on how different a situation this is from the discovery of many other neurodegenerative disease genes. Prion protein, huntingtin, and amyloid beta were all discovered as disease proteins and are named after the pathology or disease that they cause, and to this day, we don’t have a very clear idea of what their respective native functions are. When a subset of ALS cases were linked to SOD1, it must have seemed like a home run: here, at last, is a disease that turns out to be caused by a protein whose native function has been well-understood for decades. Accordingly, early reports were overly confident that the disease mechanism would prove to be obviously related to SOD1 native function:

..our results establish a specific molecular basis for free radical damage… resulting from a structurally defective SOD with reduced activity

— [Deng 1993]

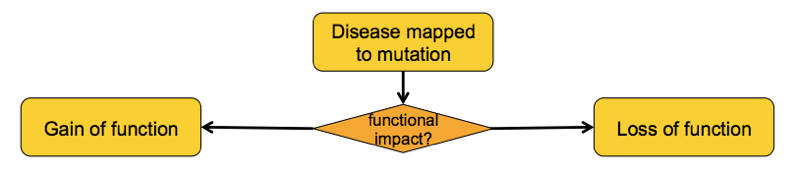

Gain vs. loss of function

In the several years after SOD1 mutations were found to be causal in a subset of ALS families, a variety of investigators did the classic set of experiments to dissect whether the mechanism was a gain or a loss of funciton. In the case of SOD1, the different ways of asking this question point pretty uniformly to a gain of function:

- Functional class of causal variants. A dominantly inherited disease could be due to haploinsufficiency, but if so, one would expect that at least a significant subset of causal variants would be clear loss-of-funciton variants - nonsense, frameshift, and splice site. In the case of SOD1, all of the originally identified variants were missense - A4V, G37R, L38V, G41S, G41D, H43R, G85R, G93A, G93C, E100G, L106V, I113T, L144F, V148G [Deng 1993, Rosen 1993]†.

- Some mutants retain native enzymatic activity. Some of the missense variants that cause SOD1 ALS (H46R, H48Q, G85R, D124V, D125H, S134N) do have reduced superoxide dismutase activity, but others (A4V, L38V, G37R, G41S, G72S, D76Y, D90A, G93A, ΔE133) retain full enzymatic activity [Borchelt 1994, Hayward 2002]. The fact that some mutants do not appear to lose their native function argues against simple haploinsufficiency and loss-of-function as a disease mechanism.

- Knockout mice have a different phenotype. A dominant disease gene with causal variants that are almost exclusively missense could still have caused disease by a dominant negative mechanism. If so, then Sod1 knockout mice should have recapitulated the disease phenotype. That didn’t turn out to be the case - instead, Sod1 knockouts have a relatively mild phenotype, with neurons more likely to die if axons are severed, but without any progressive neurodegeneration or paralysis [Reaume 1996].

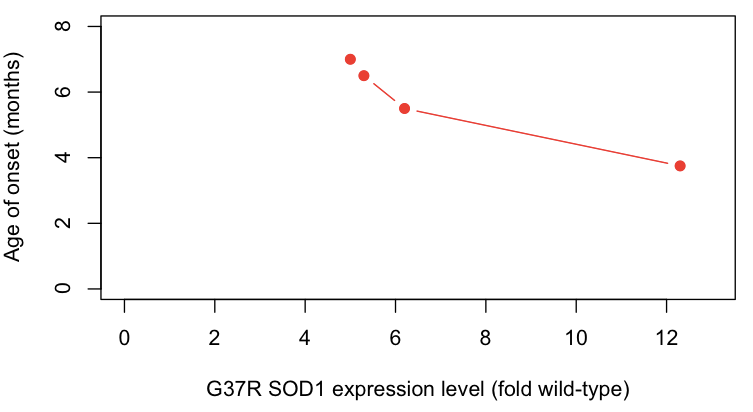

- Overexpression of mutant protein causes disease in a dose-dependent manner. Expression of G37R SOD1 in transgenic mice causes a highly penetrant ALS-like disease, with higher expression levels causing earlier onset [Wong 1995] and the presence or absence of endogenous Sod1 having no obvious effect [Bruijn 1998].

†As an interesting aside, one mutation, D90A, was reported as recessive in some families and dominant in others [Al-Chalabi 1998]. There are 136 copies of the D90A allele in ExAC, so one possibility would be that it only marginally increases ALS risk, such that disease has only limited penetrance in people with one mutant allele but the disease is more highly penetrant in people with two mutant alleles.

With regards to point #4 above, the correlation between expression level and age of onset are particularly compelling - here, I plot the data from [Wong 1995 Table 1]:

protein_level = c(12.3,6.2,5.3,5.0)

onset = c(3.75,5.5,6.5,7)

plot(protein_level, onset, xlim=c(0,13), ylim=c(0,8), xlab='G37R SOD1 expression level (fold wild-type)', ylab='Age of onset (months)', pch=19, type='b', col='#FF2016')

Based on all of the above lines of evidence, it seems that by the late 1990s, most (but not all [Saccon 2013]) investigators had become convinced that SOD1 mutations cause disease by a gain of function.

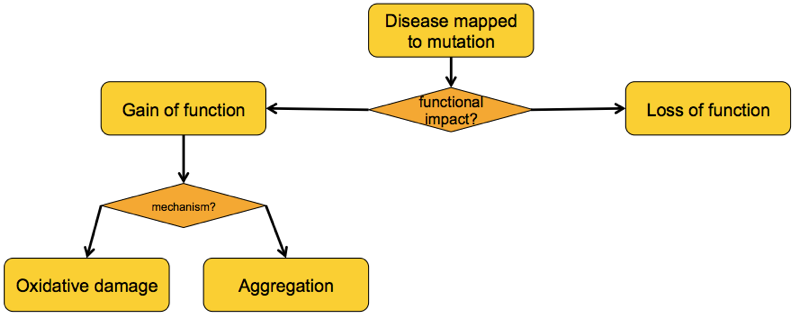

What, then, is the gained function of these mutants?

There have been a variety of theories as to the gained function of mutant SOD1 [reviewed in Ilieva 2009], some of which overlap with one another. But from my read of the literature it appears that by 2000, just two major competing schools of thought had emerged: the “oxidative damage hypothesis” and the “aggregation hypothesis” [Cleveland & Liu 2000].

The oxidative damage hypothesis

The oxidative damage hypothesis held that SOD1 mutations altered the enzymatic activity of SOD1, possibly by allowing it to bind copper but not zinc. The result was purported to be that mutant SOD1 sometimes runs in reverse, catalyzing the conversion of H2O2 into O2-, and worse, allows the nascent O2- to react with nitric oxide (NO) to yield peroxynitrite (ONOO-):

This peroxynitrite, so the hypothesis went, was then responsible for causing oxidative damage to a variety of cellular proteins and ultimately leading to motor neuron death. The evidence for the oxidative damage hypothesis came from a variety of in vitro and cell culture studies.

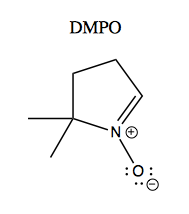

One study examined free radical formation catalyzed by recombinant G93A versus wild-type SOD1 purified from Sf9 cells [Yim 1996]. Apparently many radicals are too reactive to study directly, so they used a trick called a spin trapping. The principle of this is that radicals have electron spin that can be measured using electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy (EPR), which is to electrons as NMR is to nuclei. The problem is that many radicals of interest are so reactive that they are present too transiently to measure with EPR. So they used a small molecule called DMPO, a “spin trap”, which reacts with radicals while preserving their spin. Here’s what it looks like:

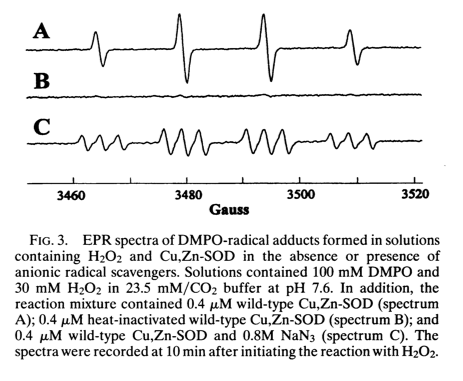

After DMPO reacts with a free radical, it gives different EPR spectra depending upon what the radical was. This is shown in Figure 3 of [Yim 1996]:

Spectrum A is DMPO-OH created by combining DMPO and H2O2 in the presence of wild-type SOD1. Spectrum B is just the flat line of unreacted DMPO, here obtained as a control where DMPO and H2O2 are combined with heat-inactivated wild-type SOD1. Spectrum C is DMPO-N·3 created by combining DMPO and sodium azide, NaN3 in the presence of wild-type SOD1. Thus, following Le Chatelier’s principle, if you add enough hydrogen peroxide even to wild-type SOD1, you can get it to run in reverse and create radicals instead of defusing them, and you can use the DPMO + EPR system to measure the creation of these radicals.

SOD1 can only be enzymatically active when metallated - it relies on both its Cu2+ and Zn2+ ions in order to perform catalysis. The investigators measured the molarity of the enzyme and of the metals in the protein they purified from Sf9 cells, and estimated that the wild-type protein was 95% metallated and the G93A mutant was 90% metallated. When the measured superoxide dismutase activity, the mutant was just slightly lower than the wild-type, consistent with the 90% vs. 95% metallation difference. So far, the enzymes appeared to be nearly equivalent in activity.

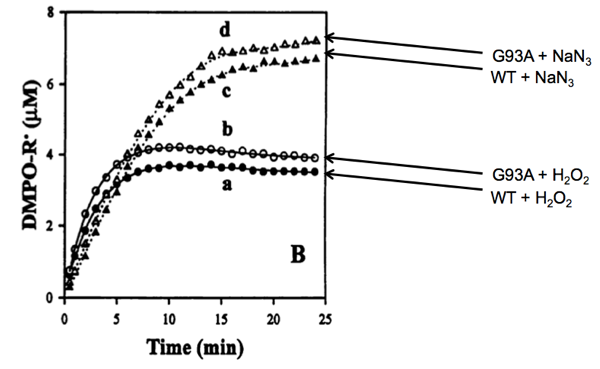

But when they measured the ability of the enzymes to create radicals using their spin trapping system, they saw a subtle difference:

Above: Yim 1996 Figure 4B, annotated.

Whether combined with hydrogen peroxide or sodium azide, the mutant enzyme (at 0.4 μM) appeared to produce a slightly greater amount of radicals than the wild-type enzyme (also at 0.4 μM). Indeed, by measuring the formation of DMPO-OH at different concentrations of H2O2 they measured the Michaelis constant (Km) of wild-type SOD1 at 34.5 mM. The Km of G93A SOD1 appeared to be slightly lower, 28.5 mM. Meanwhile, the kcat - the rate of catalysis for forming DMPO-OH - was not discernibly different for the two proteins (5 reactions per minute). Their argument for the oxidative damage hypothesis, then, was that it appeared that the G93A mutation caused SOD1 to have stronger affinity for H2O2 than wild-type SOD1 does. As a result, H2O2 formed from O2- would be less likely to be quickly released from the enzyme and more likely to stick around and get catalyzed back into a free radical.

The differences - both in the curves above, and in the calculated Km values, are extremely small. Moreover, the measured Km value for G93A SOD1 (28.5 mM), while somewhat lower than that of wild-type SOD1, was still about 1000 times higher than the physiological concentration of H2O2 in the cell, which is said to be around 30 to 50 μM [Gautam 2006]. So even supposing that the measured differences are real, how physiologically relevant could they be?

Yet the oxidative damage hypothesis proved to be a hot area of study. Another study around the same time [Wiedau-Pazos 1996] used a similar experimental system and found similar results. They purified their SOD1 from yeast and studied the ability of wild-type plus two mutants, A4V and G93A, to catalyze formation of DMPO-OH. The mutants both had stronger activity, and this could be abolished by adding a copper chelator, suggesting that perhaps it depended upon copper in the active site of SOD1. They also found that adding their copper chelator reduced apoptosis in neural cell culture models of four different mutants (A4V, G37R, G41D, and G85R).

A commentary on the oxidative damage hypothesis [Marx 1996] declared that the results from the in vitro studies were consistent with concurrent work claiming a therapeutic benefit of treating SOD1 G93A mice with an antioxidant supplement of vitamin E and selenium [Gurney 1996]. But as Jamie Heywood later showed, you can’t believe everything you read about therapeutics in that mouse model [Scott 2008]. Vitamin E has gone on to show mixed results in humans [Desnuelle 2001, Ascherio 2005, Graf 2005] and, as far as I can tell, never become standard of care in ALS.

Following these findings, a couple of other studies found reduced or altered Zn2+ binding in SOD1 mutants [Lyons 1996, Crow 1997] and one even went so far as to declared that “this defect is likely related to the enzymatic gain of function that is causative in ALS” [Lyons 1996]. A study using rat primary motor neuron cultures found that depleting zinc from either mutant or wild-type SOD1 rendered the enzyme toxic to neurons, while depleting nitric oxide by using nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitors rescued toxicity [Estevez 1999]. Thus, it was supposed, the ability of mutant SOD1 to bind copper but not zinc is what caused it to run backwards and created peroxynitrite from hydrogen peroxide.

All of the major lines of evidence for the oxidative damage hypothesis seem to have come from these sorts of in vitro and cell culture studies. As Don Cleveland pointed out [Cleveland & Liu 2000], the hypothesis wasn’t very consistent with in vivo data. Overexpression of G85R SOD1 in transgenic mice caused a disease that was unaltered by the level of co-expression of wild-type SOD1 [Bruijn 1998]. If the disease was caused by oxidative damage due to the mutant enzyme binding O2-, creating H2O2 and not letting go, then having at least some wild-type enzyme around to compete with the mutant enzyme for O2- should have slowed disease progression. In a letter to Science, Cleveland’s group also raised a series of other objections to the Estevez paper [Williamson 2000] The full text] of their objections, including Estevez’ reply, is a good read. Estevez makes a point about the oxidative damage hypothesis which, really, can be applied to any hypothesis and is worth bearing in mind throughout this post:

The ultimate test… will lie in whether it can yield a useful treatment for stopping the progression of ALS

What was needed was a way to interrogate the oxidative damage hypothesis in vivo. Conveniently, around that time, a yeast mutagenesis screen identified a protein whose job is to load Cu2+ into SOD1, dubbed “copper chaperone for SOD1” [Culotta 1997]. The gene encoding its human ortholog is named CCS. As it turns out, CCS is virtually essential for SOD1 activity in vivo: Ccs knockout mice have only ~15% wild-type levels of SOD1 enzyme activity in relevant tissues such as spinal cord [Wong 2000]. This provided an elegant platform to test the oxidative damage hypothesis in vivo. Because SOD1 is enzymatically inactive without Cu2+, genetic deletion of CCS would be expected to make it impossible for mutant SOD1 to perform reverse catalysis and generate superoxide and therefore peroxynitrite. So if the oxidative damage hypothesis were correct, then Ccs knockout should attenuate disease in mice overexpressing mutant SOD1. But in fact, when the experiment was done by crossing three different transgenic mouse lines - G37R, G85R, and G93A - to Ccs knockouts, there was no difference in disease course [Subramaniam 2002].

Another argument against oxidative damage as the sole or primary driver of pathology in ALS comes simply from the diversity of mutants [Valentine & Hart 2003]. Mutations in the beta barrel of SOD1 result in metal-binding and enzymatic activity in in vitro systems comparable to wild-type SOD1, whereas mutations in or near the catalytic site of SOD1 cause a near-total loss of metal-binding ability, at least in expression systems from which recombinant proteins are purified. Of all the mutants, only H48Q both binds Cu and Zn and yet has little native SOD activity. Valentine argues it is hard to imagine that the metal-deficient class of mutants are sufficiently metallated in vivo as to be able to efficiently catalyze the production of superoxide. Given that there appear to be at least three different classes of disease-causing mutation with regard to metal-binding and enzymatic activity, it is hard to imagine that all of the mutants cause disease by oxidative damage through the metal-binding site. If there is a single unifying disease mechanism for all of these mutants, therefore, it would appear that the oxidative damage hypothesis is not a strong candidate.

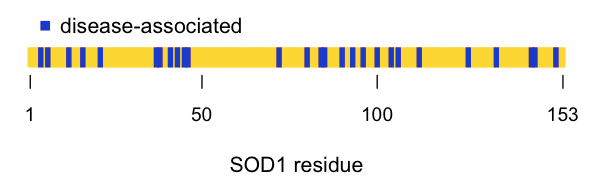

And what about the position of various mutants within the protein’s structure? I saw references that claim that there are 90 [Rowland & Shneider 2001] or >100 [Guegan & Przedborski 2003] different reported disease-causing variants in SOD1, but none of these references actually list all of the disease variants, let alone cite all of the supporting literature evidence for each one. To try to get a list of all the reportedly pathogenic variants in SOD1, I instead visited ClinVar, searched for SOD1, and selected display max 100 records, format tabular (text). I got these results, which contain lots of rubbish but also 31 actual missense variants reported to cause disease. I extracted them with:

cat media/2015/04/clinvar_sod1_search_results.txt | egrep -o "p\.[A-Za-z0-9]+" | sed 's/p.//'

And I got this list. ClinVar uses the canonical codon numbering scheme which includes the N-terminal methionine, whereas the structure of SOD1 that I’m using [PDB# 2SOD]], and all of the SOD1 literature, uses a numbering scheme shifted by -1, so I extracted the numbers, subtracted 1 from each, and turned it into an R vector with:

cat media/2015/04/clinvar_sod1_search_results.txt | egrep -o "p\.[A-Za-z0-9]+" | sed 's/p.//' | egrep -o "[0-9]+" | sort -n | uniq | awk 'BEGIN {print "c(" } {print ($1 -1)" ,"} END {print ")"}' | tr '\n' ' '

If we then plot the position of the disease-associated residues in the linear amino acid sequence, it looks pretty much random:

all_res = 1:153

dz = c( 4 , 6 , 12 , 16 , 21 , 37 , 38 , 41 , 43 , 45 , 46 , 72 , 80 , 84 , 85 , 90 , 93 , 96 , 100 , 104 , 106 , 112 , 126 , 134 , 144 , 145 , 151 )

plot(x=all_res, y=rep(1, length(all_res)), type='h', lwd=4, lend=1, col='#FFD700', axes=FALSE, xlab='SOD1 residue', ylab='', ylim=c(0,10))

points(x=dz, y=rep(1, length(dz)), type='h', lwd=4, lend=1, col='#0000CD')

axis(side=1, at=c(1,50,100,153), labels=c(1,50,100,153), lwd=0, lwd.ticks=1, cex.axis=.9)

legend(x=1,y=2.5,c('disease-associated'),col='#0000CD',pch=15,bty='n')

Even better, we can look at the positions of the disease-associated residues in the native structure. I swapped in a awk '{print ($1 -1)"+"}' | tr -d '\n' to get list of residues I could plug into my PyMOL code to highlight all of the reported disease residues in blue. I used the structure of recombinant human SOD1 [PDB# 1SOS, [Parge 1992]]:

fetch 1sos

bg_color white

hide everything

show cartoon, chain A

color 0xFFD700, chain A

color 0x0000CD, chain A and (resi 4+6+12+16+21+37+38+41+43+45+46+72+80+84+85+90+93+96+100+104+106+112+126+134+144+145+151)

show sticks, chain A and (resi 4+6+12+16+21+37+38+41+43+45+46+72+80+84+85+90+93+96+100+104+106+112+126+134+144+145+151)

show spheres, inorganic and chain A

color 0xC77F33, chain A and element Cu

color 0x7C7FAF, chain A and element Zn

As you can see, the disease-associated residues are scattered throughout the protein. Indeed, of the six histidines involved in coordinating the metal ions, only one (H46) is associated with SOD1 ALS in the ClinVar list. (Another one of the six, H48, is also implicated according to [Valentine & Hart 2003], see above). While none of this in any way disproves the oxidative damage hypothesis, to me, the seemingly random distribution of causal mutations doesn’t obviously point to the catalytic site as being important.

Aggregation hypothesis

A fact not often mentioned in the papers on the oxidative damage hypothesis is that SOD1 ALS patients have ubiquitinated aggregates of SOD1 in the neurons and astrocytes of their spinal cord [Kato 2000]. This feature is recapitulated in G93A SOD1 mice, and indeed, lower-order multimers can be detected months before large aggregates appear [Johnston 2000]. That doesn’t necessarily mean that such misfolding is causal - it could be a side effect of a disease process - but it at least raises the possibility. An alternative to the oxidative damage hypothesis, then, is that SOD1 mutants misfold to form oligomers and ultimately aggregates, and that one or more of these misfolded species is toxic. In the literature, this seems to be referred to as the “aggregation hypothesis”, though it is worth noting that for SOD1 ALS as for most neurodegenerative diseases, it is unclear both where the toxic species might lie on the spectrum from small oligomer to large aggregate, and by what mechanism, exactly, that species might be toxic.

How would one go about testing the aggregation hypothesis? One obvious first step would be simply to check whether the mutants do indeed have increased propensity to aggregate. And indeed, a number of studies using a variety of different experimental paradigms have shown that disease-associated mutations do indeed predispose SOD1 to misfold and aggregate in vitro [Rodriguez 2002, Lindberg 2002, Stathopulos & Rumfeldt 2003]. Of course, that alone doesn’t prove that misfolding or aggregation causes the disease, but it is worth reviewing some of the experimental approaches and results here.

A number of in vitro experiments have examined the equilibrium folding and unfolding of SOD1. In these, SOD1 is usually purified either from human erythrocytes [Rakhit 2004] or bacteria [Getzoff 1992, Crow 1997, Stathopulos & Rumfeldt 2003, Rakhit 2004]. In the case of bacteria, some investigators co-express CCS in order to get the SOD1 metallated [Lindberg 2002]. In these studies, the term holo (whole, complete; think “holistic”) refers to metallated SOD1, while apo (apart, away; think “apology”) refers to non-metallated SOD1. Apo SOD1 can be created by dialyzing holo SOD1 with EDTA to chelate the metal ions [Lindberg 2002].

One study examined the equilibrium unfolding of SOD1 in GdnHCl according to CD spectra, as a function of metallation, concentration, and various mutations [Lindberg 2002]. Apo SOD1 unfolds at much lower combination of [GdnHCl] and concentration than holo SOD1 does - in other words, the metal ions seem to stabilize the native conformation. In Figure 3 they perform equilibrium unfolding of wild-type SOD1, five reportedy pathogenic mutants (A4V, C6F, D90A, G93A, and G93C, though note that D90A probably confers low disease risk, see above) and one not-known-to-be-pathogenic substitution, C6A, as a control. They do the unfolding with both GdnHCl (top panels) and urea (bottom panels), each in the presence of a reducing agent, TCEP. The readout is circular dichroism intensity at 216 nm (for GdnHCl) and 230 nm (for urea). All of these experiments are done at a concentration of 35 μM SOD1 dimers. Across the board, the pathogenic mutations cause the apo protein to unfold at a lower [GdnHCl] or [urea] value. Most of the mutations also cause the holo protein to unfold at a lower denaturant concentration too.

Interestingly, the first experiments at the top of that paper were done in an oxidizing environment, and they observed an inflection that they believe resulted from non-native intermolecular disulfide crosslinks: “The reason for this perturbation is most likely crosslinking of free thiol side chains in the denatured ensemble that would not take place in the reducing environment in the cell” [Lindberg 2002]. Subsequent experiments in that paper used TCEP as a reducing agent to avoid this problem. Yet subsequent work has shown that intermolecular disulfide crosslinks may actually be a feature of SOD1 ALS in vivo [Karch 2009 and see other post].

Another study measured thermal denaturation of mutant and wild-type SOD1 using differential scanning calorimetry [Stathopulos & Rumfeldt 2003]. They examined four disease mutants (A4V, G93A, G93R, E100G) plus wild-type SOD1. After initial purification of the proteins, they used the pyrogallol assay (described above) to measure superoxide dismutase activity and found that all of these mutants, as long as they were in their metallated holo form, had activity comparable to wild-type SOD1. The apo forms were all inactive. As shown in Table 1, across every comparison, apo SOD1 has a lower melting point than holo SOD1, and mutants (whether apo or holo) have a lower melting point than the corresponding wild-type. They also measured the kinetics of unfolding in 6M or 4M GdnHCl by UV spectroscopy and found that the mutants unfolded faster [Fig 2]. The melting point was also correlated with the propensity of the mutants to aggregate, as measured by the amount of trifluoroethanol (which induces aggregation) required to be added to the solution to cause the protein to aggregate (measured by thioflavin T, which fluoresces when bound to amyloid) [Fig 4]. It is interesting to ponder this correlation - presumably, heat helps ease the transition from native to intermediate, rather than affecting the transition from intermeidate to aggregate per se. If so, does the fact that melting point is correlated with propensity to aggregate in TFE indicate that unfolding is the rate-limiting step in SOD1 aggregation?

Also interestingly, although the TFE-induced SOD1 aggregates do exhibit some elevated ThT fluorescence it is only 2-3 fold, whereas apparently “true” amyloids can give on the order of 1000-fold increases in ThT fluorescence. The aggregates also gave less of a Congo red signal. Both of these facts are apparently also true of in vivo SOD1 aggregates, and based on these observations, the authors argue that perhaps SOD1 aggregates are “distinct from amyloid”, whatever amyloid is. They also say that the appearance of the TFE-induced aggregates on electron microscopy resembles the in vivo ones.

Finally, they used right-angle light scattering, which as far as I understand is a measure of turbidity / presence of large insoluble aggregates. This experiment is a bit suspect to me because they didn’t study all four of their mutants (G93R is conspicuously absent from Fig 6), and they only looked at the apo, not holo forms. In any case, the mutants all aggregated (as measured by light scattering) at lower temperatures than wild-type.

Together, experiments such as those described in these two references [Lindberg 2002, Stathopulos & Rumfeldt 2003] established that SOD1 mutants, as a class, seem to have a greater propensity to aggregate than wild-type SOD1 does. But one difficulty in interpreting such studies is that they usually do not include an exhaustive panel of all ALS-causing SOD1 mutations - instead, each investigator looks at a few mutations that they are interested in and for which they have expression constructs to hand. Moreover, it has been argued that just about any protein can aggregate if the conditions are just wrong - for instance, even myoglobin can form amyloid [Fandrich 2001], so it is not clear how well the results from these in vitro experiments predict that mutant SOD1 will actually misfold and cause disease in vivo.

One very satisfying result would be if one could show that the propensity of the various mutants to misfold in vitro correlates with the clinical aspects of the diseases they cause in patients. Yet my read of the literature in this area is that there is no clear and reproducible positive result. One study culled 620 SOD1 ALS cases from the literature and found that their disease duration correlated with several predicted biochemical properties of the corresponding mutants, such as hydrophobicity, loss of α-helices, etc [Wang 2008]. But that paper only spends a bit of time discussing empirically determined aggregation properties of the mutants. That’s probably because the empirical measurements in the literature are pretty scattershot. Most of the studies I read while writing this post focused on just a few hand-picked mutations. The closest thing to an exhaustive panel of mutations was one study that transiently transfected HEK cells to express each of 21 different mutants and then extracted aggregates using detergent [Prudencio 2009]. And in that study, there was no clear correlation between “aggregation propensity” (amount of insoluble SOD1 extracted from cells) and age of onset or disease duration - only in a post-hoc grouping analysis was any correlation seen. Another subsequent study has also failed to find any meaningful correlation of in vitro unfolding or aggregation measurements with disease clinical characteristics [Vassall & Stubbs 2011], consistent with earlier results [Ratovitski 1999].

An alternative approach to demonstrating that aggregation (or misfolding, generally) is causal in SOD1 ALS would be to show that the disease is transmissible. This rests on the logic that if the misfolded protein can trigger disease in an animal that wouldn’t have gotten sick otherwise, then the misfolded protein has to be causal. As reviewed in my previous post, there has been some success in infecting cultured cells with SOD1 aggregates [Munch 2011]. In that study, they purified H46R SOD1 from Sf9 cells, created aggregates with 20% trifluoroethanol, and labeled them with Dylight649, a red fluorophore. They then dumped the aggregates onto N2a cells and looked both for uptake of aggregates and formation of new aggregates from endogenously expressed SOD1. The most compelling figure is Figure 4, which shows representative images where red exogenous aggregates have indeed been taken up into a cell, and normally diffuse green signal from endogenously expressed H46R SOD1-GFP turns into aggregated puncta, suggesting new aggregates have been formed.

Yet the ability to transmit aggregates to cells doesn’t necessarily show that this is what causes clinical disease. For that you need in vivo experiments. From what I’ve seen there has been only one report on the in vivo transmissibility of SOD1 ALS to mice [Ayers 2014]. In Figure 3, they show survival curves, where uninoculated mice expressing G85R SOD1-YFP remain healhty out to 20 months, while some of the same mice injected with spinal cord homogenates from aged G93A SOD1 mice (which do get spontaneous disease) become sick within a few months, though not with a 100% attack rate. The disease can be serially passaged, too: spinal cord homogenates from the paralyzed inoculated G85R SOD1-YFP mice can transmit the disease to mice of the same genotype, this time with a 100% attack rate and shorter incubation time. There is a missing control in this figure: there are no G85R SOD1-YFP mice inoculated with spinal cord homogenate from healthy wild-type mice. Also, the G85R SOD1-YFP mice represent the most positive result from this study - in contrast, the G93A spinal cord homogenates did not accelerate disease in G93A mice nor transmit disease to mice overexpressing wild-type SOD1. But these limitations don’t mean that the mechanism isn’t fundamentally one of templated protein misfolding. For whatever reason, not many misfolded proteins seem to be as readily transmissible as PrPSc is, yet for some (say, alpha synuclein) there is still a great amount of evidence indicating that, at the molecular level, there is a prion mechanism at play. The same could be true for SOD1.

Supposing that misfolding and perhaps aggregation are responsible for the disease, a next question becomes whether we can elucidate the pathway to a neurotoxic species, and identify places where we could intervene. In this area, an interesting development has been what I’ll call the “monomer hypothesis” - that SOD1 dimers must dissociate into monomers before aggregating.

The earliest reference to the monomer hypothesis that I found actually worked exclusively with wild-type SOD1 - no mutants - and simply examined the effects of oxidative damage to the protein [Rakhit 2004]. Instead of TFE or heat, they used “metal-catalyzed oxidation” (exposure to CuCl2) to oxidize SOD1, and then used a small molecule called ANS, which fluoresces when bound to exposed hydrophobic patches, to measure unfolding/aggregation over a range of SOD1 concentrations from 0 to 100 μM. They found that oxidation results in ANS fluorescence (and thus presumably SOD1 unfolding) at lower SOD1 concentrations.

One the most impactful aspects of that study was that according to dynamic light scattering and analytical ultracentrifugation [a method reviewed in Cole 2008], the oxidized SOD1 was present partly as a monomer instead of a dimer. Thus, they formulated a model (Figure 7) that SOD1 dimers must first become zinc-deficient, and then dissociate into monomers, before aggregating. The mutants, it was supposed, must have a higher energy in the native state, such that the barrier to transitioning into a zinc-deficient monomer is relatively lower.

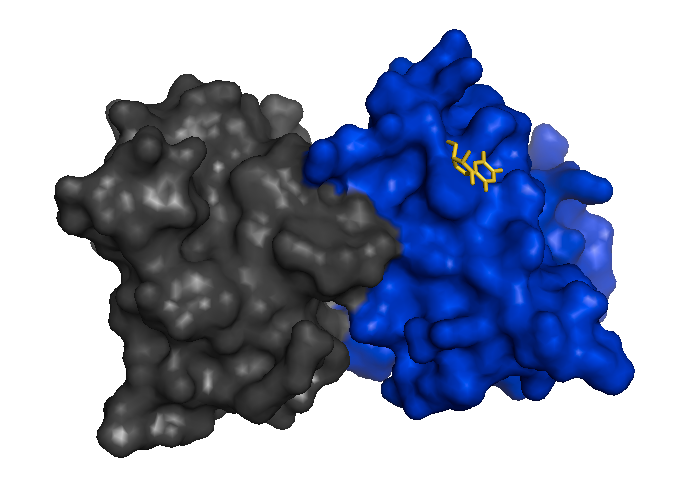

Mutant SOD1 monomers have since been observed in mouse spinal cord extracts [Karch 2009] and stabilizing the dimer to prevent its dissociation is considered as one possible therapeutic strategy [Wright 2013], analogous to how tafamidis stabilizes transthyretin tetramers. Here is a structure of an I113T SOD1 dimer bound to 5-fluorouiridine (5-FUrd), one of the proposed compounds to prevent dissociation into monomers [PDB# 4A7S, Wright 2013]:

fetch 4a7s

bg_color white

hide everything

show surface

color 0x0000CD, chain A

color 0x444444, chain F

show sticks, organic

color 0xFFD700, organic

Conclusions

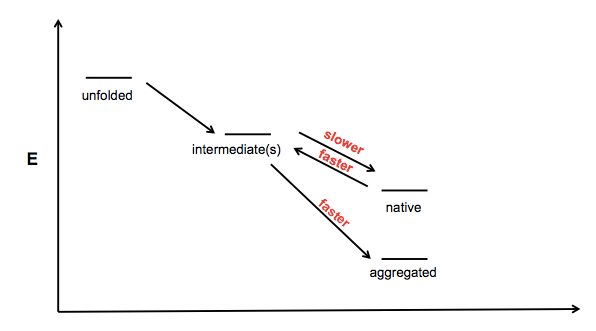

In trying to think about how SOD1 mutations might cause protein aggregation, I drew a little schematic:

This is sort of vague and ill-conceived - I guess the x axis is just “foldedness” or something - but the idea is that there exists one or more partially folded intermediates on the road from unfolded polypeptide to native protein, and aggregates might be formed from one of these partially folded intermediates. I can imagine at least three mechanisms by which a mutation would increase a protein’s propensity to aggregate:

- Making the protein reach its native fold more slowly

- Making the protein unfold from its native state more rapidly

- Making the protein convert from intermediate to aggregate more rapidly

The astute reader will note that a fourth potential cell in this matrix is a slower transition from aggregate to intermediate, but I have omitted this as aggregation is often assumed to be irreversible under physiological conditions.

The data for SOD1 indicate that various measures of native state stability - melting point, amount of GdnHCl required for denaturation, etc. - are reduced in the mutants. This is an interesting contrast to prion protein - the PrP mutants P102L and E200K do not appear to decrease the Tm or affect GdnHCl denaturation of PrP [Swietnicki 1998]. Does this mean that the rate-limiting step in misfolding/aggregation is different for these two proteins? Could it be, for instance, that SOD1 mutations mostly act to destabilize the native state (points 1 and 2 above) while PrP mutations only cause disease if they promote stability of aggregates (point 3 above)? Or similarly, perhaps they promote some secondary intermediate on the pathway to aggregation? It is interesting to speculate, but I haven’t yet dreamed up an experiment that would clearly distinguish between these mechanisms.