Tominersen being rebooted for early HD

These are my notes from Roche’s webinar on their decision to re-launch clinical studies of tominersen, presented at the HDSA Research Webinar Series on Jan 20, 2022. This webinar was intended for the patient community, the video has been posted publicly online so I’m going ahead and blogging it.

context & news

Tominersen is an experimental ASO drug designed to lower huntingtin, the causal protein in Huntington’s disease. It was developed by Ionis and licensed by Roche/Genentech for clinical development. Last spring, tominersen failed in a Phase III trial, GENERATION-HD1, when dosing was stopped at the recommendation of an Independent Data Monitoring Committee. We later learned why: on a variety of clinical measures, patients on tominersen actually appeared to do worse than patients on placebo in the first 17 months of the trial. Earlier this week, a press release from Ionis indicated that Roche now plans to re-launch clinical studies of tominersen, with a new Phase II trial in “a younger adult patient population with less disease burden”. Yesterday, two Roche scientists, Dr. Lauren Boak and Dr. Peter McColgan, presented the rationale behind this decision at an HDSA Research Webinar. The full video of their talk is available on YouTube:

premise of post hoc analyses

Dr. Boak began by giving a thorough introduction to the therapeutic hypothesis behind tominersen, the clinical development program to date, and the findings that led to last year’s termination of GENERATION-HD1 Phase III trial. I won’t repeat all of that background here, because it’s covered in my last post on tominersen. The only thing new to me was that GENERATION-HD1, which is continuing to evaluate patient outcomes after the cessaton of dosing, will have its last study visit circa March 2022, and participants will be unblinded in June 2022.

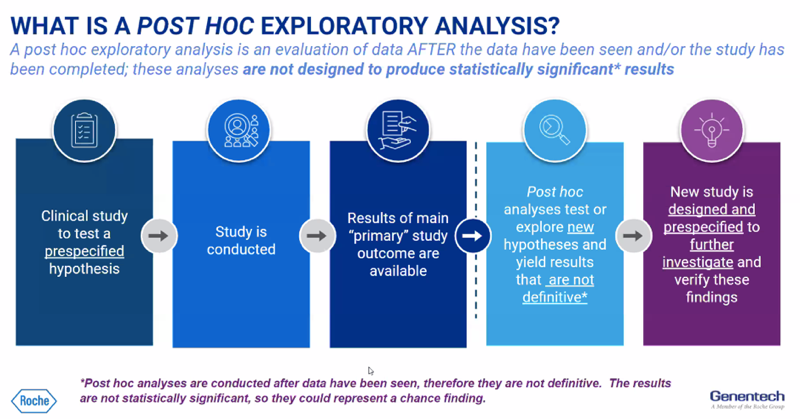

Importantly, though, Dr. McColgan gave a primer on what a “post hoc” analysis is, and why one should take it with a grain of salt:

This is important, so it merits a brief recap here.

There are lots of degrees of freedom in clinical trials: different ways you could slice and dice the patient population, different outcomes that have been measured, different timepoints at which they were measured, and so forth. Given those degrees of freedom, in any clinical trial, no matter how abysmally it failed, one could almost always find some metric in some group of patients at some timepoint that looked positive. This engenders a risk of wishful thinking: if we just believed whichever analysis looked most positive, then we’d end up advancing or approving lots of drugs that are ineffective or even harmful. To guard against such wishful thinking, the standard practice required by regulators is that clinical trials be designed around a single pre-specified primary endpoint (outcome measure), a pre-specified stopping time, and that analysis should include all patients who were intended to be treated in the trial. These constraints ensure that, if a drug really is effective, the trial will provide definitive evidence of that efficacy.

But, one can also examine the data from failed clinical trials in a more exploratory fashion, to try to guess why a drug failed, or to surmise in what type of patients it might possibly have worked after all. Such analyses will never be definitive and won’t be the basis for approving a drug, but they could generate hypotheses. They could motivate a company to launch a new clinical trial with a different patient population, different dosing regimen, or some other difference versus the original trial, designed to eventually deliver a definitive answer of whether the drug is effective.

So here’s the big caveat: what Roche is presenting in this webinar are exploratory, post hoc analyses. These analyses not intended to be statistically convincing, and cannot provide evidence of anything. All they can do is generate hypotheses that Roche can study in future clinical trials.

Dr. McColgan next introduced the variables on which the post hoc analysis was based. They stratified patients on three variables: age, CAP score, and dose. CAP score is a function of a patient’s age and CAG repeat length, so it’s correlated with HD disease burden, but note that it does not directly measure disease burden — it’s not a clinical metric, just a predictor.

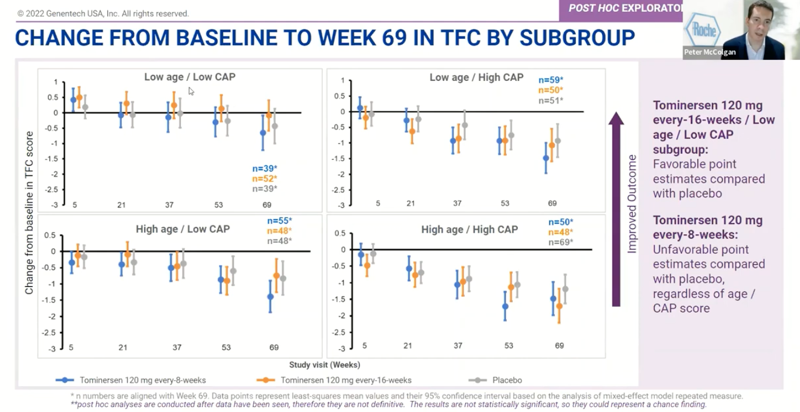

In the Q8W (120 mg every 8 weeks) dosing group, tominersen looked worse than placebo across the board, so this dosing regime will not be explored further. In the Q16W (120 mg every 16 weeks) dosing group, however, the overall picture was not so different from placebo for many outcome measures, and so they decided to divide the patients into four groups: low age / low CAP, low age / high CAP, high age / low CAP, and high age / high CAP. The low age / low CAP group was on average 40 years old and had 46 CAG repeats, whereas the high age / high CAP group was on average 56 years old and had 44 CAG repeats. Within each group, the Q16W and placebo groups were reasonably well-matched. They then proceeded to repeat their analyses of clinical outcomes, CSF neurofilament, CSF mutant huntingtin, brain imaging, and safety, within each group.

post hoc analysis results

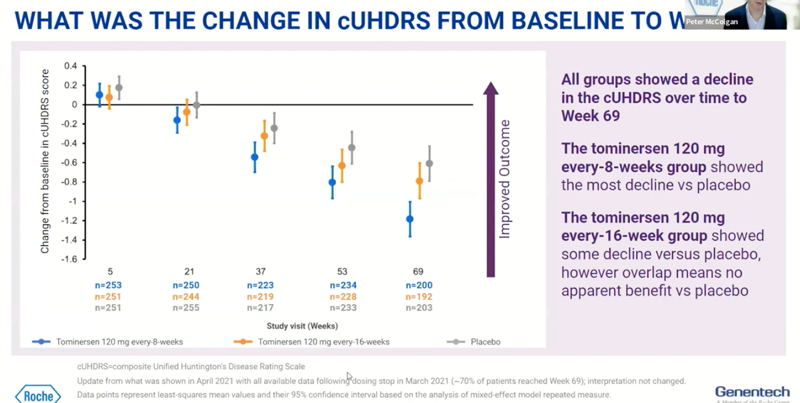

Dr. McColgan began with cUHDRS, the unified HD rating scale that was the study’s primary outcome. As with the preliminary dataset showed in April, the final analysis shows that Q8W did worse than placebo, while Q16W did maybe slightly worse, though it’s not significantly different. The error bars here are 95% confidence intervals, so visually, when error bars of two points overlap, that means they are not significantly different at the P = 0.05 threshold.

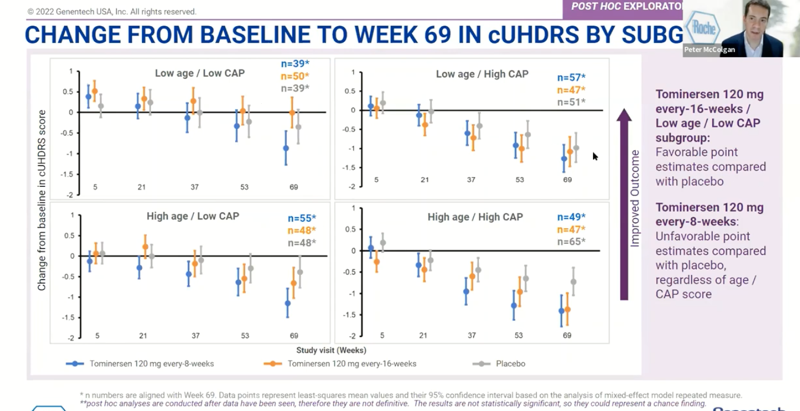

When that same plot was stratified by the four subgroups, here’s what it looked like:

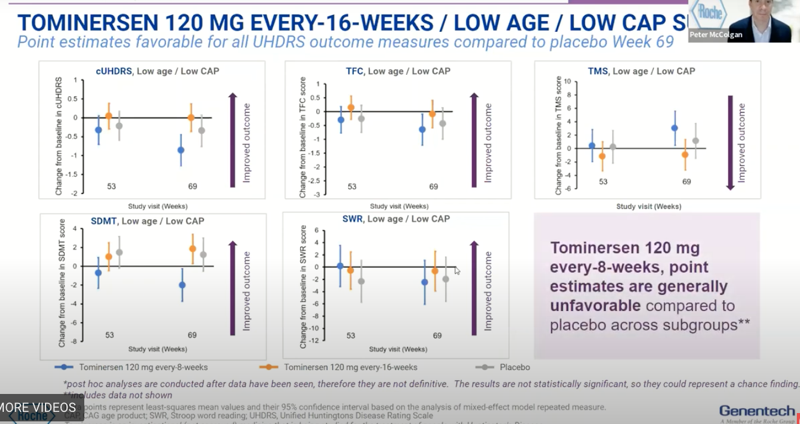

Now we’re looking at smaller groups, which means statistical power is reduced. None of the differences appear to be even nominally statistically significant, and that’s without accounting for the multiple testing burden of looking at four groups separately. But setting aside statistics and just speaking in terms of point estimates, Dr. McColgan pointed out that Q16W appeared to do slightly worse than placebo in 3 of the 4 groups but slightly better than placebo in the low age / low CAP group (top left, orange points higher than respective gray points). Because cUHDRS is a composite of a number of different tests and scores, Dr. McColgan later went on to break down cUHDRS into all the individual measures, and this same trend was observed in the low age / low CAP group across each:

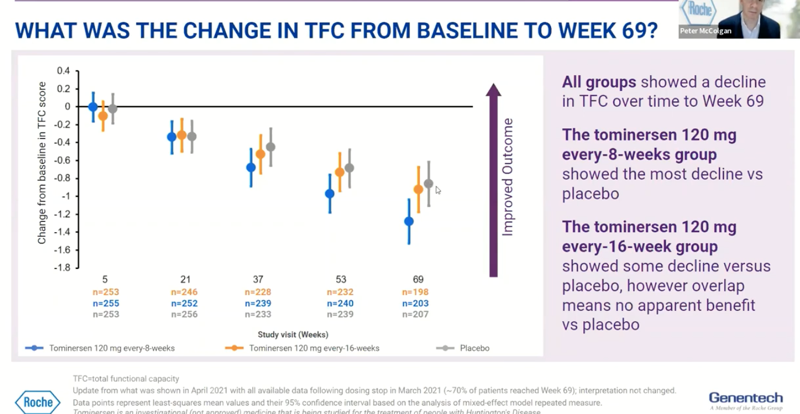

A similar trend could be seen for total functional capacity (TFC), a measure of HD patients’ ability to carry out tasks of daily living. It worsened for Q16W overall:

But the point estimates were slightly higher than placebo in the low age / low CAP subgroup:

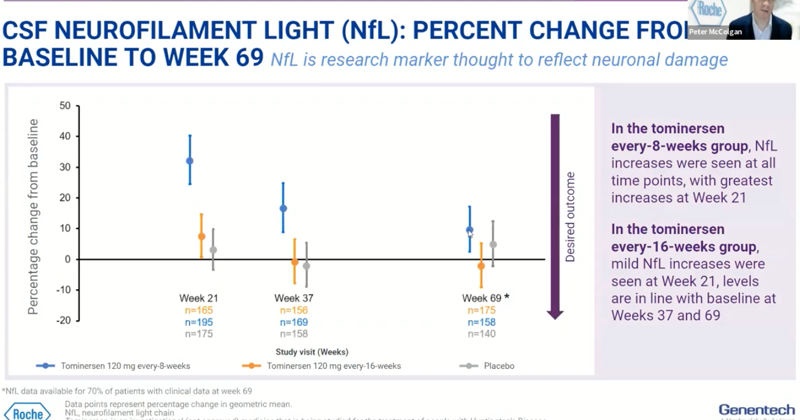

For CSF neurofilament light (NfL), a marker of neuronal damage (lower is better), Q16W overall was similar to placebo, though with a point estimate slightly worse than placebo at 21 weeks and slightly better than placebo by 69 weeks:

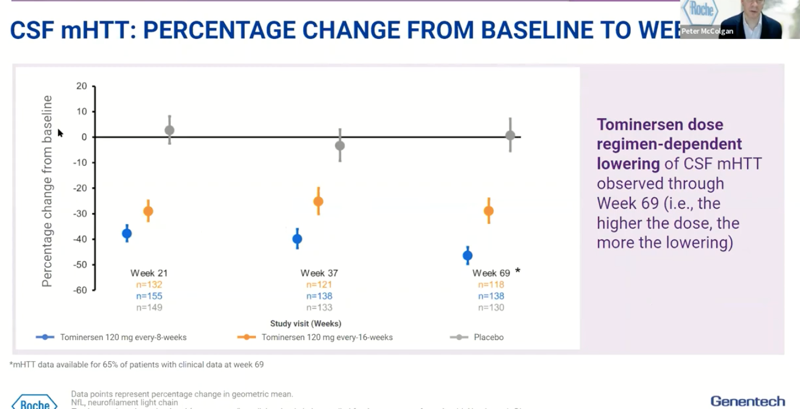

For CSF mutant huntingtin, a measure of target engagement (is the drug doing its job), at 69 weeks it looks like the Q8W group had about 48% knockdown, while Q16W was more like 28% knockdown:

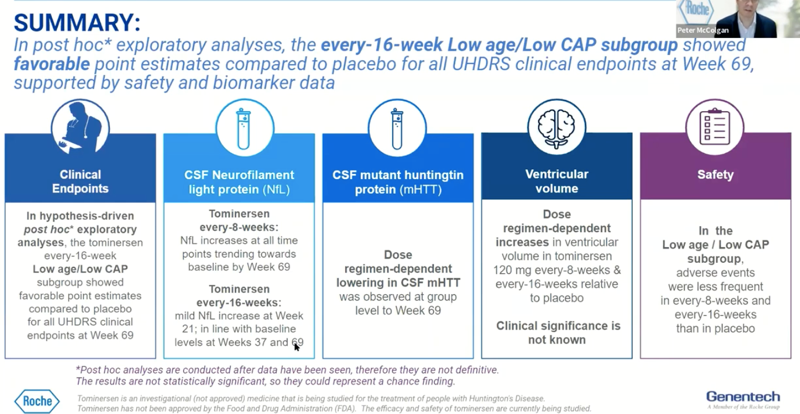

Dr. McColgan stated (though I didn’t see any plots showing this) that CSF NfL and CSF mHTT results were similar across subgroups.

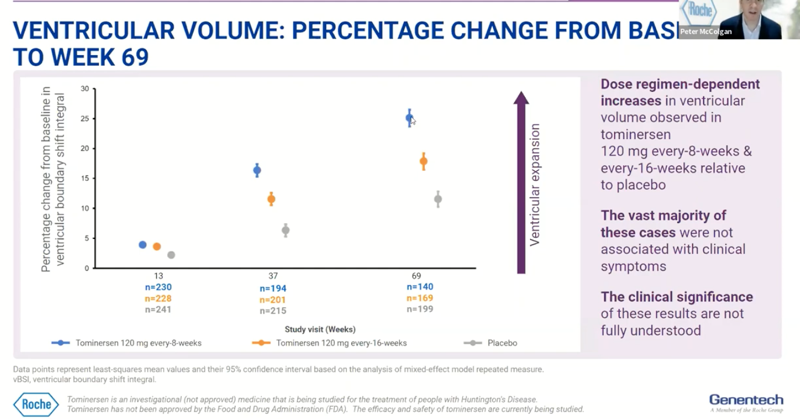

He next moved on to brain imaging. Ventricular volume was dose-dependently increased, as shown back in April. He said that the clinical significance of this is not known, and most cases did not have clinically apparent signs.

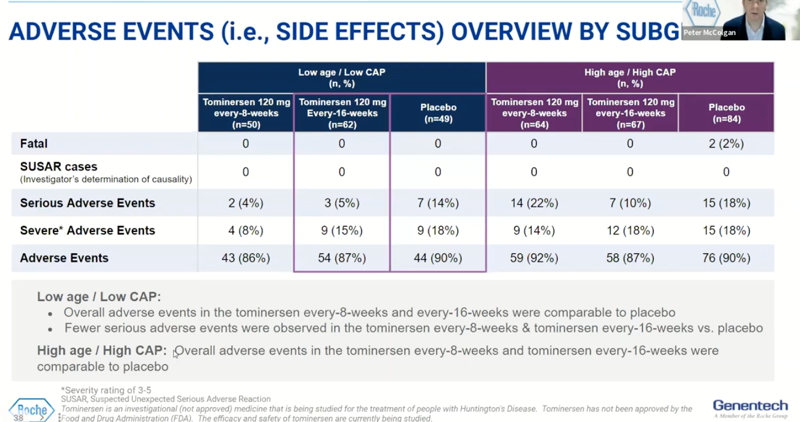

Finally, he showed the final adverse event (safety) data stratified by subgroup. In the low age / low CAP subgroup, adverse events were no more common than placebo. (Later, in the Q&A, he emphasized again that “we’re confident there’s no difference from placebo in this subgroup”.)

He summarized all the above points as follows:

By way of conclusion, Dr. McColgan emphasized that GENERATION-HD1 did not meet its primary endpoint, and that while the post hoc subgroup analyses are suggestive of a potential for tominersen to benefit younger patients with lower disease burden, such benefit can only be confirmed through a new, prospectively designed, randomized controlled study. Roche is now in the process of designing a new Phase II trial in such patients. They believe that the safety analysis combined with potential for clinical benefit support this decision.

He finally ended by thanking the patient community for their participation in the clinical program, without which none of this would have been possible.

analysis and discussion

The slight trend towards better outcomes in low age, low CAP, Q16W participants replicates across a number of outcome measures, but remember, those are all the same patients. If random variation resulted in that being a subgroup of patients who just happened to progress less quickly, then we’d expect that to show up across a variety of measures, just as shown here.

Over the 69 weeks of the trial, the low age, low CAP, placebo participants declined by about half a point from baseline on the cUHDRS. The low age, low CAP, Q16W individuals were right at 0, at their baseline at 69 weeks. However, they were about half a point above baseline at 5 weeks into the trial, and the relative differential between Q16W and placebo among these low age, low CAP individuals was maintained from week 5 to week 69 even as both groups declined in absolute terms. Therefore, in order to believe that the difference between these groups at 69 weeks was real, you have to believe that the difference was already present just 5 weeks in. In contrast, if the difference 5 weeks in was just chance variation, then the rate of progression from week 5 to week 69 appears virtually identical in both groups.

When tominersen first failed in March 2021, HDBuzz contemplated three possible reasons (out of many): disease stage, potency, and allele specificity. Roche’s decision to continue development seems predicated on “disease stage” as being the answer here. But if it were that simple, it’s not clear why the subgroup analysis would need to be stratified on both age and CAP score. After all, CAP score already includes age as one component. If the issue were simply disease stage, one would expect that patients with high age but low CAP score (e.g. someone who is 60 but only has 40 CAG repeats) could also benefit from drug. So perhaps instead, Roche’s hypothesis is that it’s specifically an interaction between age and disease stage. That’s possible, but this also highlights why post hoc analyses are so risky: one can slice and dice almost any dataset such that there exists some subgroup that appeared to benefit from drug. Accordingly, Dr. McColgan emphasized, over and over again, that the idea of tominersen being effective in low age, low CAP people is simply a hypothesis and that there is not yet any evidence to support this.

While it’s reassuring that adverse events were no more common in the low age, low CAP, Q16W group than in placebo, recall that the overall trial did not fail due to adverse events per se. It failed because patients on drug did worse than those on placebo. This was not intepreted as a “safety signal”, and the original press release said that “No new or emerging safety signals were identified for tominersen in the review of the data from this study”. On GENERATION-HD1’s primary outcome of cUHDRS, Q16W patients overall averaged slightly worse than placebo patients overall. The low age / low CAP group overall averaged slightly better than placebo, and Roche’s hypothesis is that this is because the drug might be effective in this subgroup. But it’s important to remember that the alternative hypothesis is that the better outcome in low age / low CAP is just due to random variation, and that on average, such patients in a new prospective trial would actually be expected do worse than placebo.

When Dr. Scott Schobel announced the preliminary trial results in April, he noted that one motivation for continuing study visits and outcome measures despite cessation of drug dosing, was to see whether the worsened outcomes observed in treated patients were reversible after they stopped taking drug. Such data were not yet presented in yesterday’s webinar. But given that the last study visit for GENERATION-HD1 is only a couple of months away, it seems reasonable to hope that such data will become available before a new Phase II trial begins. If the worsened outcomes observed in GENERATION-HD1 do indeed prove reversible, that finding would help to mitigate the risk of exposing additional patients to tominersen.

Overall, the data presented yesterday are a reminder of just how difficult a job it is to usher a drug through clinical development. For a drug to succeed, so many things have to go right. To list just a few: the drug has to be well-enough tolerated, the drug has to engage its target, that target has to be disease-relevant, the patients have to be at a disease stage where the drug can work, the disease has to progress at the predicted rate in placebo-treated patients, and the benefit of the drug has to turn up in a measured outcome within a specified timeframe. To fail, all it takes is for any one of these pieces to be off. It’s natural, then, that when a drug fails, one goes back and looks at each variable to try to guess whether the outcome would have been different if, say, we’d selected a slightly different group of patients. At each juncture, it’s a matter of balancing the risks — risks of making patients worse, and risks of wasting time and goodwill and dollars — against the probability of finally finding an effective treatment. In this case, Roche has decided that the potential benefits outweigh the risks, and given the appetite of the HD community for participating in research, it seems likely that many patients will be willing to enroll in another trial to find out if they’re right. All we can do is wait and see.