anle138b: the new most promising experimental compound for treating prion diseases

Data newly published in the past week clearly establish anle138b (above) as the most promising experimental compound so far for the treatment of prion diseases [Wagner 2013 (ft, supp1, supp2)].

This announcement has been a long time in the making. A few years ago, the Groschup lab in Riems, Germany screened two subsets of the ChemBridge DIVERSet compound library, looking for molecules that could inhibit the formation of proteinase K-resistant PrP (hereafter “PrP-res”), a proxy for disease-causing conformations of PrP, and validated the top hits in mouse models. They eventually published two papers on their findings [Geissen 2011, Leidel 2011], but they also synthesized their own library of variations on the most promising molecular motif – diphenylpyrazoles – and way back in 2009 they filed U.S. Patent US20110293520 covering this whole class of compounds including, above all, their most powerful molecule: anle138b.

To be clear at the outset, anle138b is no cure: it delays, but does not prevent, prion-induced death in mice. But it’s the best thing so far. anle138b inhibits PrP-res formation in vitro, showed excellent blood-brain barrier penetrance, and brought about fairly dramatic survival improvements in a battery of experiments in prion-infected mice.

The paper includes scads of data on in vitro performance, behavioral symptoms, PrPSc accumulation in the spleen, and much more. But the mouse survival data are always what I find most compelling, so I summarize the results of the main mouse survival experiment with anle138b in the following table. [update 2013-05-01: table modified to reflect differences in dose]

| dose | treatment started | median treated survival | median control survival | delay | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 mg twice/day | 0 dpi | 355 days | 180 days | 97% | .0001 |

| 5 mg once/day | 80 dpi | 242 days | 168 days | 44% | .0001 |

| 5 mg once/day | 120 dpi | 224 days | 172 days | 30% | .0001 |

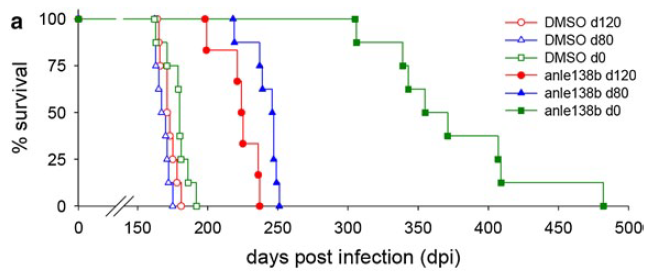

All of the above experiments used C57BL/6 mice inoculated intracerebrally with 30μL 1% RML homogenate and treated orally. Here’s what these data look like in survival curve form (Fig 3 from the paper):

The ~30% delay in onset with treatment at 120 dpi is arguably the most positive result ever reported with a treatment so late in the course of infection. (I’ll return to why “arguably” in a moment). Indeed, few researchers have even bothered to test other compounds so late in the disease, since it is clear that most anti-prion compounds (and anle138b is no exception) have time-dependent effects, where early treatment is far more effective than late treatment.

In fact, Wagner calls the 80 dpi and 120 dpi experiments ‘treatment started after onset of disease’. It’s true that some symptoms can be observed by these timepoints (behavioral signs by 80 dpi and weight loss as well by 120 dpi). Mice at these timepoints still do not have what researchers call ‘clinical signs’, though, and whether they correspond to times in a human disease course when sporadic CJD patients would be available for treatment is not entirely clear. That’s a broader issue that applies not only to anle138b, so I will address it more deeply in my next post.

But I do want to address briefly the issue of how to compare this study to previous ones. The authors state that:

To the best of our knowledge, the prolongation of survival even in late-stage treatment experiments obtained in prion-infected mice is by far the largest that has been found for any drug-like compound tested so far (Suppl. Fig. 20).

That’s sort of true. Data from other studies are beautifully summarized in Fig S20 on p. 31 of supp1. But the use of absolute days rather than percent delay in onset/death is a bit misleading. Different mouse models get sick at different times – incubation time of prions in mice is exquisitely correlated with PrP expression level of the mouse and infectious titer of the inoculum. It’s also affected by prion strain and mouse background. So for instance, although anle138b at 0 dpi ranks #1 in the “Δ, days” column, with a 175-day difference in survival, and cpd-B has only an 111-day difference, if you convert these to percentages of control incubation time you get 175/180 = 97% delay for anle138b and 111/63 = 176% delay for cpd-B. (This is also true of pentosan polysulfate, see my next post). So six years ago, cpd-B showed even greater inhibitory effects than anle138b has today, yet it never made it to clinical trials.

Why not? Largely because cpd-B’s effects were strain-dependent [Kawasaki 2007]. The 176% delay cited above was for RML prions, but cpd-B did next to nothing against 22L prions. Wagner notes this as a crucial difference between anle138b and cpd-B:

compound B was reported to lack activity for certain prion strains and—at the biochemical level—to be less efficient for double glycosylated PrPSc species, whereas we show that anle138b is active in all strains tested (including human CJD and BSE-derived strains)

The “we show that anle138b is active” here refers to an in vitro assay called protein misfolding cyclic amplification (PMCA) [Saborio 2001]. Anle138b appeared to work equally well against two other rodent strains (ME7 and 301C) and two human strains (sCJD and vCJD/BSE). It also showed no evidence of strain selection by glycosylation state. That’s all great news and clearly differentiates anle138b from cpd-B, whose strain specificity was already clear in vitro [see Kawasaki 2007's Fig 1]. But I’ll be cautious in my optimism until I see in vivo evidence of strain-universality.

Which brings us to mechanism of action. Wagner provides a wide variety of evidence that anle138b’s mechanism of action is “modulation of aggregation at the oligomer level”. Indeed, extensive evidence is presented for interference in alpha-synuclein aggregation and the alleviation of certain phenotypes in mouse models of Parkinson’s Disease. If anle138b really does work against more than one neurodegenerative disease – despite these diseases involving completely different proteins – then this paper is truly big, big news. And also truly mysterious. Wagner states they were unable to determine which amino acids on PrP anle138b binds to, because it does not bind to PrP monomers at all. Because we don’t know what amino acids are bound, one can’t rule out whether familial prion disease mutations would affect the binding, which is another reason I’ll be cautious about the strain specificity issue for now.

The dose – 5 to 10 mg/day for each mouse – is really pretty large for a drug. If you figure a typical mouse is 25g, then that can be roughly extrapolated to 5 or 10/.025 mg/kg * 3/37 * 70 = ~1.1g – 2.2g of drug per day for a 70 kg human. Yet no toxicity at all was observed, even in mice receiving the drug for over a year. pp. 25-30 of supp2 give the data from acute toxicity experiments, which can be summarized as follows: no toxicity even at 2000 mg/kg in rats and mice (that’s like a person taking 140 grams of the drug), no toxicity in human cell cultures, no interference with cytoskeletal proteins. The authors state that “further preclinical safety studies will be required prior to clinical studies in humans”, but so far everything looks good.

Though no one appears to be talking in any detail about potential clinical trials yet, the authors do state that their toxicity experiments were undertaken “in preparation for a first clinical trial”. That’s exciting news. As I’ll argue in my next post, the biggest question for human trials will be whether we can treat people early enough to make a difference.