Biochemistry 06: membranes, signaling and metabolism

These are notes from lecture 6 of Harvard Extension’s biochemistry class.

lipids and the plasma membrane

See also: The Plasma Membrane.

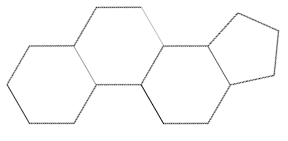

Basic structure of a sterol always contains a steroid nucleus such as gonane, with the SMILES C2C1[C@H](CCCC1)[C@H]3CC[C@H]4[C@H]([C@@H]3C2)CCC4. This is a 3 fused 6-carbon rings and 1 5-carbon ring.

Cholesterol is the most abundant sterol in animal tissue. It is a precursor to many things including the steroids which are hormones.

Fatty acids alone form a micelle. Glycerophospholipids are able to form a more rectangular structure, the lipid bilayer. With triacylglycerols the rectangular shape has a tendency to fold in on itself, resulting in a liposome. Liposomes are a way to deliver drugs across membranes. Triacylglycerol is abundant in adipose tissue.

The lipid bilayer is a fluid structure. Its thickness depends on the acyl fatty acid chains – their length, curvature and interactions with each other. Head groups are of differing sizes and interact differently with each other. The head groups move up and down and the hydrocarbon tails move around a lot.

A lipid bilayer has a melting point Tm below which it is an ordered crystalline gel, and above which it is a disordered liquid crystal. Tm depends on the length of acyl chains (more Van der Waals interactions in longer chains = higher melting point) and the degree of saturation (less tight of packing with more double bonds = higher melting point). Organisms can adjust their membrane composition to accommodate different temperatures.

Cholesterol is an important component of the plasma membrane. Its ring structure restricts movement of nearby fatty acid chains, reducing fluidity (raising melting point) but also prevents tight packing (lowering melting point), thus making the overall membrane properties more consistent over a wider range of temperatures. (It reduces the slope on the %crystalline vs. temperature plot.)

The plasma membrane is asymmetric, with some phospholipids more abundant on one face or the other.

Flip flop (movement of a phospholipid molecule from one leaflet to the other) by diffusion is very unfavorable because the hydrophilic head cap has to go through the hydrophobic center, so its t½ is on the order of days. Flippase can do the job much faster. Lateral diffusion within a leaflet is also very fast.

membrane proteins

Main articles: The Plasma Membrane & The Secretory Pathway

Membrane proteins can be integral, which can only be removed and studied by using detergents to solubilize the membrane. Integral membrane proteins can usually be predicted based on sequence. Glancing at a hydrophobicity plot (hydrophobicity index vs. codon number) can tell you which parts will be membrane-spanning. Membrane proteins with beta sheets can form a “beta barrel” pore in the membrane.

Then there are peripheral membrane proteins which are easily dissociable (they just associate with the membrane through hydrogen bonding and “electrostatic interactions”).

And there are lipid-linked proteins which are difficult to remove except by using phospholipases to cleave them off. The lipid linkers include palmitoyl, N-myristoyl, and farnesyl on the cytosolic leaflet and GPI on the exoplasmic leaflet.

The plasma membrane can be studied using FRAP. Again, see The Plasma Membrane.

Lipid rafts are microdomains within a membrane enriched for glycosphingolipids and cholesterol. It is thicker and more ordered than the rest of the membrane. Components of the raft (including proteins) move together, which is thought to be important for signaling.

membrane transport

Main article: The Plasma Membrane.

Types of membrane transport:

- nonmediated. Transport across the membrane can be simple diffusion down a gradient, which works for some nonpolar molecules such as O2 and CO2.

- passive-mediated aka facilitated diffusion. This uses a transport protein to aid movement down the gradient. The transport can be mediated by a channel or a carrier protein. See more below.

- active transport. This moves things up a gradient and is endergonic. This is divided into primary active, which hydrolyze ATP and secondary active which rely on coupling unfavorable transport with favorable transport. (The gradient that allows favorable transport for secondary actives is maintained by other hard-working primary actives).

Here’s the difference between carriers and channels:

- carriers bind with specificity. Their rates are below the limit of diffusion (i.e. slower than channels) though faster than with no catalyst. They are saturable and therefore exhibit Michaelis-Menten kinetics (see enzyme kinetics).

- channels have specificity only based on their size and charge. The rate of transport can approach the limit of unhindered diffusion. It is not saturable. Channels are often gated by voltage or by ligands (either extracellular or intracellular ligands).

Transport proteins can also be classified into uniporters, symporters and antiporters. The slides for lecture make it sound as though this distinction is orthogonal to the carrier/channel distinction, but from what I see online uniporters may be carriers or channels while all symporter and antiporters are carriers.

We discussed the same examples that were discussed in Cell Biology last semester.

receptors

A receptor is a protein that binds a specific ligand/signaling molecule to elicit a specific response.

A second messenger is a small molecule that transduces the signal from a receptor to intracellular targets.

Our focus will be on metabolism. For this system, the ligands are hormones. They are released by endocrine cells, travel through the bloodstream, and bind to receptors on the surface of target cells.

Signal transduction systems have a few important features:

- Specificity for the particular ligand.

- Amplification by enzyme cascades. One first enzyme associated with a receptor can activate many second enzymes which can each activate many third enzymes.

- Desensitization and adaptation. Signals can shut themselves off.

Receptor/ligand interactions follow a saturation curve just like Michaelis-Menten kinetics. Instead of Km, you have Kd, the dissociation constant. This is the ligand concentration at which half of receptors are bound with ligand. Lower means higher affinity. (This appears to be the same Kd used to measure antibody affinity).

We’ll discuss G protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) and receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs). Robert Lefkowitz and Brian Kobilka won the 2012 Nobel prize for clarifying how GPCRs work.

G protein coupled receptors

Main article: Signal Transduction

GPCRs have two states:

- αGDPβγ is the inactive state.

- αGTP + βγ is the active state.

Ligand binding to the GPCR triggers the dissociation of the G protein subunits and the release of the GDP. GTP can subsequently bind the alpha subunit, thus reaching the active state. The alpha subunit can later hydrolyze the GTP to GDP and then can re-associate with the beta and gamma subunits, thus returning to the inactive state.

The most common cancer-causing mutation in GPCRs is a mutation in the GTPase catalytic domain which disables the alpha subunit from hydrolyzing GTP, thus leaving that GPCR in a permanent “on” state.

example 1: beta-adrenergic receptors

An example of a GPCR pathway is epinephrine binding to beta-adrenergic receptors. After epinephrine binds, Gα binds and thus activates adenylate cyclase, which catalyzes conversion of ATP to cAMP. cAMP then activates protein kinase A, which can then phosphorylate S and T residues on many other protein targets.

Ways that a signal cascade can be turned off:

- The intrinsic GTPase activity of Gα

- Short half life of second messengers. For instance cAMP is hydrolyzed to 5′AMP.

- Phosphatases de-activate downstream targets

- Receptor is desensitized to signal, for instance by beta-arrestin.

Beta-arrestin both renders the GPCR unable to interact with the G protein and causes endocytosis of the receptor.

example 2: alpha-adrenergic receptors

Main article: Signal Transduction

This is the IP3/DAG pathway. Epinephrine binds to alpha-adrenergic GPCR, and the G protein activates phospholipase C, which cleaves PIP2 to yield IP3 and DAG. DAG activates protein kinase C which phosphorylates many substrates. IP3 opens an IP3-sensitive calcium channel on the ER membrane, releasing Ca2+ into the cytosol, which also activates protein kinase C.

receptor tyrosine kinases

Main article: Regulation of Transcription through Signal Transduction

Each receptor is a monomer; ligand binding causes homodimerization. The two receptors then phosphorylate each other, opening up a binding site via which they can activate other proteins which can lead to cellular responses. Those latter proteins are called “relay proteins.”

misc other facts about receptors

The insulin receptor is like a receptor tyrosine kinase but is constitutively dimerized. Insulin binding causes an unbelievably complicated signaling cascade.

Some ligands can cross membranes and then bind to intracellular receptors. Example: glucocorticoid hormones. The bound receptors then bind hormone response elements (HREs) in DNA and act as transcription factors.

metabolism

Metabolism is the sum of all catabolic and anabolic processes. Catabolism is the breakdown of macromolecules into free energy (usually stored in ATP) and building blocks. Anabolism is the assembly of macromolecules using free energy and building blocks.

Here are some metabolic steps that happen when you eat:

- Salivary amylase begins to break starch into glucose.

- Gastric and pancreatic proteases such as trypsin and chymotrypsin break proteins into amino acids.

- Lipases in small intenstines release fatty acids from triacylglycerides.

- Glucose, amino acids and peptides are absorbed via transporters by cells lining the intestines.

- Water-soluble molecules are transported via the hepatic portal vein to the liver for further processing.

The liver buffers the glucose concentration in the blood, for the benefit of other organs, by consuming glucose when concentrations are high and making glucose when concentrations are low.

Different hormones mediate different energy needs. Here are some examples.

- Insulin signals fuel abundance, i.e. high blood sugar. Insulin is released when blood sugar rises. The insulin signal acts to decrease the catabolism of stored fuel (use the newly arrived sugar rather than your stores, cells!) It also acts to increase the rate of fuel storage (an anabolic process). Insulin is secreted by pancreatic beta cells.

- Glucagon signals low fuel availability, i.e. low blood sugar. It stimulates the generation of glucose and the breakdown of lipid stores (both catabolic mechanisms). It is secreted by pancreatic alpha cells.

- Epinephrine represents a “fight of flight response.” It promotes the breakdown of glucose and lipid stores (catabolism). It results in increased fuel availability. It is produced in the adrenal gland.

The thermodynamics of metabolism. Recall that at equilibrium, 0 = ΔG° + RTlnKeq. Near equilibrium reactions are those with ΔG ≈ 0. This is a zone where if you add an excess of reactants or products, enzymes will work quickly to restore equilibrium. Far from equilibrium reactions are those with ΔG << 0 . Usually these are catalyzed by an enzyme that doesn’t have sufficient catalytic activity and/or is saturated, such that the reactants accumulate in vast excess of the equilibrium amounts. Because the reactant is so much more abundant than product, the reaction is highly exergonic (remember, ΔG << 0) and spontaneous, but slow – the enzyme is the rate-limiting step. Thus enzymes are often a point of regulation in metabolism.

Sometimes a far from equilibrium reaction lies upstream of a series of near equilibrium reactions. In this case the far from equilibrium reaction acts as a dam holding back what would otherwise be a rapid progression through the steps.

Why do we have far from equilibrium reactions? Here are a few steps of reasoning:

- Metabolic pathways are irreversible. In a multi-step pathway, it only takes one irreversible reaction to make the whole pathway irreversible.

- Every metabolic pathway has a “first committed step” (the point of no return), which is usually (but somehow not always) the first irreversible step.

- Catabolic and anabolic pathways differ. If A → B is irreversible, then B → A must go througha different pathway. This allows independent control of the forward and reverse pathways.

Metabolic flux is the rate of flow of metabolites (intermediates) through a metabolic pathway. The flux of intermediates is relatively constant at a “steady state”.

Cells regulate flux through a pathway by adjusting the rate of a far from equilibrium enzyme. This can be through:

- allosteric control with the allosteric regulators being substrates, products or conenzymes within the pathway. If you have a mechanism where the concentration of a product shuts off its own synthesis, that is called a feedback/control mechanism.

- covalent modification e.g. phosphorylation/dephosphorylation

- substrate cycle is using different enzymes to go in different directions. This avoids a futile cycle. For example, if glycolysis and gluconeogenesis were running in parallel the only net result would be consumption of ATP. To prevent this, they have to be regulated by different enzymes.

- genetic control – transcription, translation

Types 1-3 act in seconds or minutes, whereas type 4, the genetic mechanisms, take hours or days to have an effect.