Organic chemistry 25: Stereochemistry - diastereoselective and enantioselective reactions

These are my notes from lecture 25 of Harvard’s Chemistry 20: Organic Chemistry course, delivered by Dr. Ryan Spoering on April 8, 2015.

Diastereoselectivity

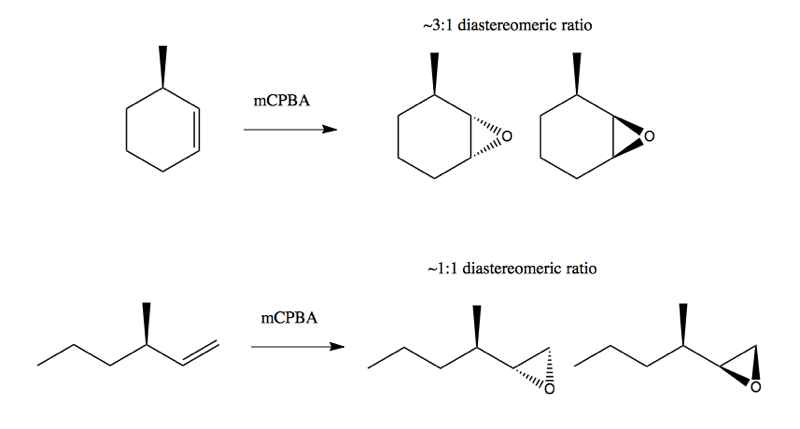

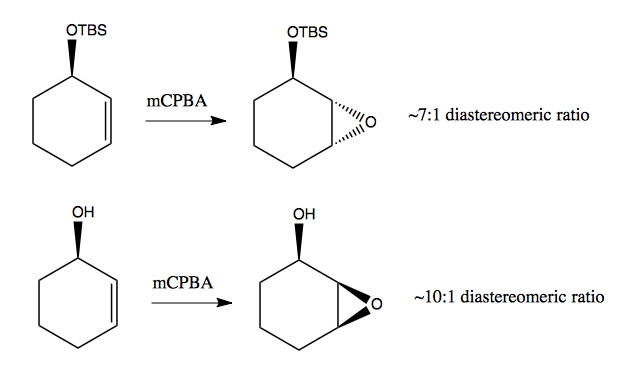

Consider these two reactions using mCPBA, introduced in lecture 19, to add an epoxide group:

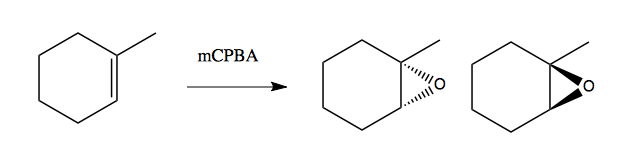

In the first case, there is some diastereoselectivity, but it is not absolute. The diastereomer at left is somewhat favored because the epoxide has less steric interference with the methyl group on the front face of the cyclohexane. In the second case, the methyl group is sufficiently out of the way of the epoxide group that you end up with no diastereoselectivity at all.

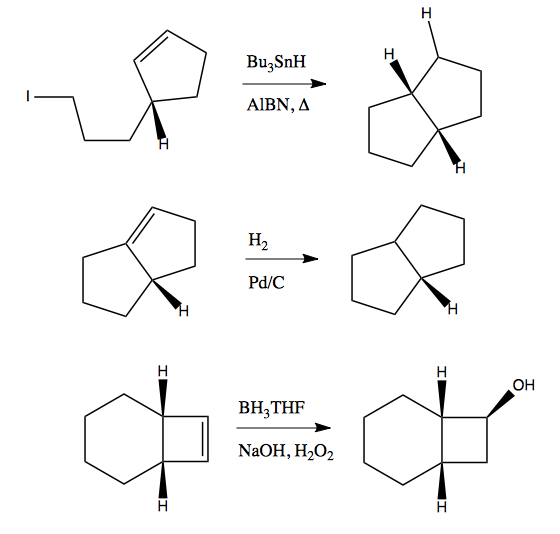

Next, here are three examples with absolute diastereoselectivity:

You can figure out why by thinking about the reactants in 3D - one face is much easier to get at than the other. For instance the second case, it’s because the molecule is not flat - the two rings are angled at one other, and it is sterically much easier to react with the convex face than the concave face. The third molecule below is achiral but has diastereotopic faces, front and back, with a convex/concave shape to it that makes the front more accessible.

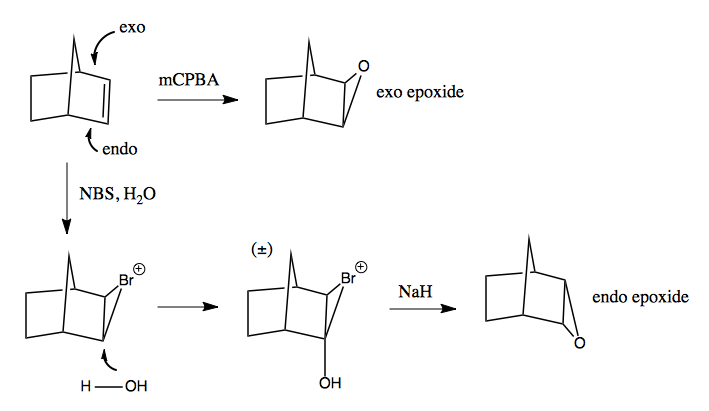

Norbornane, introduced in lecture 14, has diastereotopic faces, exo and endo. The exo is more accessible, so mCPBA will add an exo-epoxide (top). What if you want an endo-epoxide instead? You can achieve this by first brominating with NBS, then attacking with water from the endo face:

Below are two examples of directed epoxidation with opposite results due to opposite phenomena. At top, the TBS is bulky, so it is 7:1 preferred to add the epoxide to the opposing face. At bottom, the -OH can hydrogen bond with the oxygen in the epoxide, thus stabilizing it - so here it is 10:1 preferred to add the epoxide to the same face as the -OH.

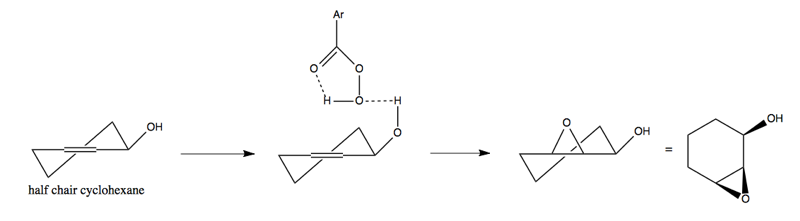

This sort of -OH-directed epoxidation is also at work in the diastereoselectivity of this reaction below, with half chair cyclohexane. The -OH hydrogen bond causes the epoxide to be added on the top (same face):

Finally, here is a concept called acyclic stereocontrol. Prof. Kishi in this department is famous for, among other things, the synthesis of monensin in 1979:

Enantioselectivity

In this example, there is no enantioselectivity, you get both products about equally:

Recall from lecture 15 that enantioselectivity is quantified as enantiomeric excess, abbreviated ee.

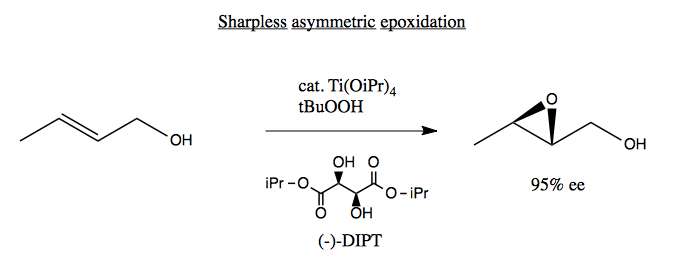

Sharpless asymmetric epoxidation is a way of epoxidating allylic alcohols. It uses a titanium catalyst derived from a tartrate:

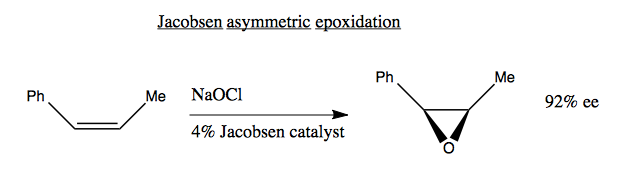

Alternately, there is Jacobsen asymmetric epoxidation, which uses bleach and the very complicated-looking Jacobsen catalyst (not pictured):

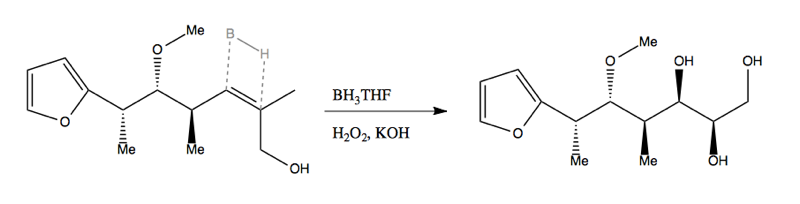

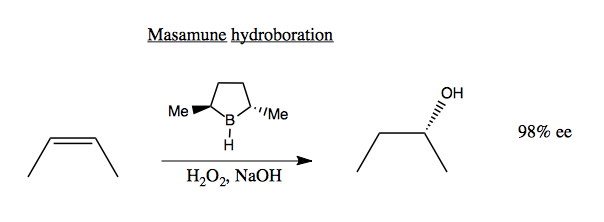

Both Sharpless and Jacobsen have the advantage that their chiral reagents are catalysts, meaning that they are not consumed in the reaction and you can use substoichiometric amounts of them. This is key because those reagents are costly to synthesize. For contrast, consider the Masasmune hydroboration (below). Here, the chiral reagent is not a catalyst but a reactant. Its stereochemistry is destroyed in the reaction, meaning you need 1:1 stoichiometry and you can’t reuse it:

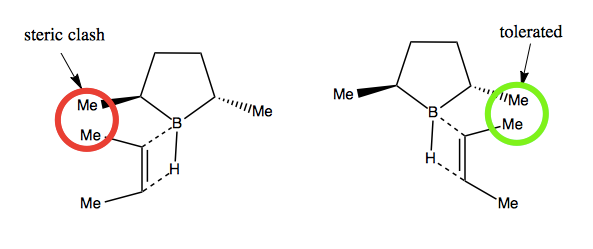

In Masamune hydroboration, the enantioselectivity is achieved via steric clash when the B-H bond aligns and hydrogen bonds with the C=C double bond: