Protective PrP missense variants

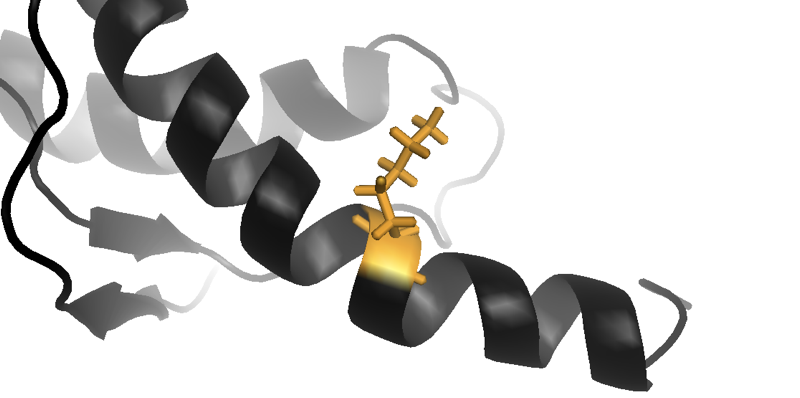

Above: close-up of the lysine (K) residue in an NMR structure of human prion protein with the E219K substitution, which reduces a person’s risk of sporadic prion disease. From structure 2LFT [Biljan 2012].

On multiple occasions recently I’ve gotten a question about the protective missense variants in the prion protein gene, PRNP. There are two questions people ask:

- Do these variants protect universally against all types of prion disease?

- Do these variants offer some insight into how to develop a therapy for prion disease?

To which the short answers are 1) not necessarily, and 2) yes, but not in the way you might think. The long answer is this blog post.

the literature on protective missense variants

What we’re talking about here are missense variants — genetic changes resulting in amino acid substitutions in the prion protein (PrP) — that reduce the risk of prion disease. There are examples documented in several species. For instance, V136A, R154H, and Q217R in sheep [Laplanche 1993, Hunter 1994, Westaway 1994, Baylis 2004], and G96S in white-tailed deer [Johnson 2006]. But in this post I’ll focus on the protective variants in humans, of which I am aware of three: G127V, M129V, and E219K.

For those who aren’t familiar, the notation used in this post is as follows. Number, letter, refers to an allele, meaning one version of a gene, so for instance 129V refers to the version of PRNP with V at codon 129. Number, letter, letter, refers to genotype, so for instance 129MM means someone who has M at codon 129 on both copies of their PRNP gene; 129MV is someone with one M and one V, 129VV is someone with V on both copies. Letter, number, letter, for instance M129V, refers to a variant, meaning the question of what someone’s genotype is. The reference allele (usually the more common version) comes before the number, and the alternate allele (usually the rarer version) comes after.

Here’s a quick rundown of what we know about each of these:

M129V

This is the most common variant in PRNP in humans, with 129V having a ~30% allele frequency in most human populatons, except among East Asians where it’s only about 2%. The variant is well-known to be associated with a longer disease duration [Pocchiari 2004] and it also affects the neuropathological presentation of the disease [Parchi 1999]. But its effects on risk are not uniform across the different types of prion disease.

Even a single 129V allele provides nearly complete protection against variant CJD [Mok 2017], and some protection against kuru [Mead 2003]. Yet 129V is associated with increased risk of human growth hormone-related CJD, perhaps due to compatibility with the genotype of the unknown infected donor [Collinge 1991, Brandel 2003, Moore 2016].

In sporadic prion disease, codon 129 exhibits heterozygote advantage. 129MV individuals have about one-third the risk of sporadic prion disease, compared to either homozygous genotype [Palmer 1991, Mead 2012].

There isn’t evidence that codon 129 affects penetrance (lifetime disease risk) in genetic prion disease. For age of onset, as reviewed here, the answer depends on which mutation. For the 6-OPRI mutation, there is evidence that 129MV is associated with a later age of onset (but still complete penetrance), compared to 129MM [Mead 2006]. For P102L, reports are conflicting [Kovacs 2005, Mead 2006, Webb 2008]. For other mutations, there is no evidence that codon 129 has any effect on age of onset.

I’m not yet sure what to make of it, but recently I noticed something interesting while looking back at some old data — Table S10 from [Minikel 2016]. Among Japanese prion disease cases with the low-penetrance V180I mutation, the genotype distribution is: 162 MM, 54 MV. The Japanese V180I allele is in cis with 129M, so that means that 25% (54/216) of trans alleles are 129V, which struck me as a dramatic enrichment, since 129V has an allele frequency of only a few percent in Japan. To see if this was significant, I did some digging and found that 129V was found to have an allele frequency of 3% among 645 Japanese controls [Nozaki 2010]. The raw numbers aren’t given, but that probably corresponds to ~39 V alleles out of 1290 chromosomes. So I did a test (in R: fisher.test(matrix(c(1290-39,39,162,54), nrow=2, byrow=T), alternative='two.sided')) and sure enough, 129V is enriched ~10-fold among V180I prion disease cases compared to the general population, P = 1 × 10-24. I don’t have any data to rule out the possibility that this is due to population stratification — maybe V180I is just more common in some region of Japan where 129V is also more common — but it is possible that 129V does actually increase risk, compared to 129M, when found in trans to V180I. I’m not sure if this is real, but one should not assume that 129V can only be helpful, not harmful, in genetic prion disease — after all, in acquired prion disease, it can be either.

E219K

E219K has an allele frequency of ~4% among East Asians and South Asians, while it is very rare in other populations. It’s been studied extensively in the Japanese population, where it has a frequency of about 6-7% [Nozaki 2010].

E219K appears to have no effect on the risk of acquired prion disease, at least for dura mater graft CJD, which is the only type of acquired prion disease common enough in Japan for there to be a reasonable amount of data [Nozaki 2010].

In sporadic prion disease, E219K is associated with reduced risk of prion disease [Shibuya 1998, Nozaki 2010]. 219EK heterozygotes appear to have about 20-fold reduced risk, as there were 3 EK and 561 EE genotypes in sporadic CJD in Japan at last count [Nozaki 2010], corresponding to an allele frequency of ~0.3% in cases, compared to 6% in controls. Oddly, we don’t yet know if the homozygous KK genotype is protective or not, because this genotype is rare enough a priori that even though zero KK sporadic CJD cases have been observed, that doesn’t yet add up to a statistically significant depletion of this genotype. (If KK risk was equal to EE risk, then out of 564 genotyped sporadic CJD cases, you’d only expect ~2 cases, so observing 0 is not too surprising.) We can say that KK almost certainly does not increase risk, though.

In genetic prion disease, it’s not clear what effect, if any, E219K might have. In the aggregate, it was reported that the K allele is depleted among genetic prion disease cases in Japan [Nozaki 2010], but it’s not yet clear to me whether that difference is statistically significant. The paper reported P < 0.001 but it is difficult to do the statistics right here — the N=214 individuals with genetic prion disease in that paper are not actually 214 independent events, as most statistical tests would assume, because there might be, say, only 20 or so genetic prion disease haplotypes in Japan (we don’t know the true number). The answer could also vary depending on which mutation a person has.

G127V

G127V has a frequency probably down arond 1% or lower in the Papua New Guinea highlands [Mead 2009] and has only ever been seen in one other individual.

Homozygotes have never been observed, but the 127GV heterozygous genotype is associated with dramatic, possiblty complete, protection from kuru [Mead 2009]. A transgenic mouse study found that 127V also protected against some variant CJD and iatrogenic CJD isolates [Asante 2015], but we don’t have any human data on this.

There are also no human data on the effects of 127V on the risk of sporadic prion disease. The mouse study found a large protective effect [Asante 2015], although that was upon inoculation with sporadic CJD brain homogenate, so it doesn’t tell us about the risk of spontaneously developing prion disease. For example, it doesn’t rule out the possibility that there might just exist a transmission barrier between 127G prions and 127V prions, with G127V individuals having equal or even increased risk to spontaneously form prions of a 127V strain.

There are no data on the effects of G127V on genetic prion disease.

summary table

Here’s a table summarizing everything I described above:

| variant | allele frequency | acquired | sporadic | genetic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M129V | ~30% worldwide | Nearly complete protection from vCJD and kuru but increased risk of HGH CJD. | Heterozygotes have ~1/3 the risk of either homozygous genotype. | No known effect for most mutations. Later onset for 6-OPRI mutation. |

| E219K | ~6% in Japan | No effect. | ~20-fold reduced risk in heterozygotes. Homozygous effect unknown. | Not clear. |

| G127V | ~1% in Papua New Guinea | Nearly complete protection from kuru. | Evidence for protection from mouse study, but no human data. | No data. |

So to summarize the answer to question #1, protective PrP missense variants do not necessarily have uniformly protective effects across different types of prion disease.

implications for therapy

Now we come to question #2 — do these protective variants offer some insight into how to develop a therapy for prion disease? Yes, absolutely: the existence of these mutations is one of many lines of evidence telling us that PrP is the cause of prion disease, and is the right drug target for therapies to prevent, delay, or treat prion disease.

But beyond that, I submit that these variants do not actually provide any more specific inspiration for how to develop a therapy. We’re not going to CRISPR these variants into people’s genomes, because we don’t have the technology to deliver CRISPR to the 100 billion neurons of the adult human brain, and even if we did, we’d probably just aim to knock out PRNP, since that is easier to do with CRISPR and has stronger proofs of concept for being protective against prion disease. And we’re probably not going to infuse PrP molecules containing these mutations into people’s brains, because we also lack the technology to deliver proteins or peptides to a wide swath of the human brain, and anyway it’s not clear whether a recombinant protein floating around unanchored would have the same protective effect as PrP anchored to the cell surface, where it’s supposed to be. (People have tried this peptide infusion idea in mouse models [Furuya 2006], but the results haven’t been too promising). There’s also an idea that maybe these protective missense variants can somehow provide inspiration for a small molecule drug for prion disease, which sounds great on the face of it, but it’s just not obvious how exactly you would design that molecule. One study used a computational approach to try to identify molecules that had structural similarity to the parts of PrP containing protective variants, and then tested some of the candidate molecules in cell culture [Perrier 2000]. But the molecules all had EC50 values of >15 μM in cell culture (that’s not very potent), and a later study could not replicate any binding to PrP nor any activity in cell culture [Kamatari 2013].

If anyone has specific ideas for how to translate these protective variants into a therapy, I’d be curious to hear them, but from everything I’ve seen and read, the translation into therapy is anything but obvious. And while these variants are clearly protective — sometimes dramatically so — in some forms of prion disease, we do not have for them nearly the proof of concept that we have for lowering PrP. As reviewed here, for lowering PrP, we know there is total protection in knockouts [Bueler 1993], there is a dose-response curve across a wide range of expression levels [Bueler 1994, Fischer 1996], PrP is needed not only for replication but also neurotoxicity [Brandner 1996], and shutting off PrP expression is beneficial even after the disease process has begun [Mallucci 2003, Safar 2005]. The protective missense variants provide one further line of evidence pointing to PrP as a drug target, but they do not open up a more promising therapeutic strategy than PrP lowering.