Antisense part I: the basics

antisense for prion disease is in the pipeline

Yesterday Sonia announced that we are working with Ionis Pharmaceuticals in an effort to develop an antisense drug for prion disease. While it is still early, and any human trials are years away, antisense is a rational therapeutic modality for this disease, with sound precedent for safety and potency in humans. That makes this collaboration the most exciting development so far in our quest for prion disease therapeutic.

Over the past few years I have spent a lot of time reading about antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) and trying to understand as much as I can about what is known about this class of drugs. This blog post will kick off a series of posts in which I talk through what I’ve learned. But I’m still far from being an expert on this subject, so please forgive any errors, and feel free to leave me a comment below.

what are ASOs, and how do they work?

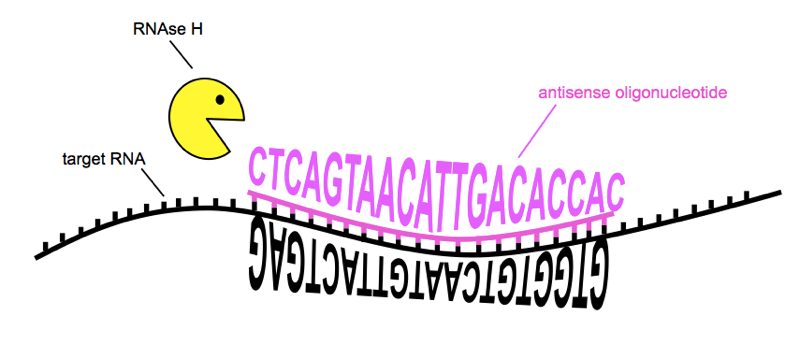

ASOs are short sequences of nucleotides, often 15 - 30 bases long, similar to DNA or RNA but chemically modified for pharmacokinetic stability [Bennett 2017]. They can be designed to have sequences that are antisense (reverse complement) to the sequence of an RNA molecule from a gene of interest. The ASO binds to the target RNA molecule according to Watson-Crick base pairing: C-G, A-T. The ASO can then affect that RNA molecule in a number of different ways, which I will discuss in more detail in the next post in this series, Antisense part II: mechanism of action. Which mechanism an ASO has is a function of both its chemistry (see Antisense part III: chemistries) and the sequence to which it is targeted.

For now, the most important point is that the ASO can cause the RNA to be cleaved by the enzyme RNAse H and degraded, lowering RNA levels and thereby lowering protein levels. This is the mechanism we are interested in for prion disease. It’s also worth noting that ASOs can be designed to modulate splicing of the RNA, causing an exon to be preferentially included or excluded — this is the mechanism of an approved ASO drug described further below.

ASOs can reduce the amount of a target RNA by bringing about RNAse H cleavage. Sequences of RNA and ASO are from [Kordasiewicz 2012]

In prion disease, the mechanism we are interested in is bringing about cleavage of the target RNA, which is PRNP RNA, in order to lower prion protein (PrP) levels. For reasons explained below, we are interested in non-allele-specific lowering of PRNP RNA, meaning we simply want to reduce all prion protein in the brain, and develop one drug suitable for all prion disease patients. We’re not targeting a particular genetic mutation.

Unlike CRISPR or siRNA, ASOs do not require a viral vector for delivery. Naked ASOs can enter cells in vivo and are active in the cytoplasm and in the nucleus, as explained more in Antisense part IV: cell biology. But as of today, there is no known chemistry or delivery method for enabling ASOs to cross the blood-brain barrier. So, we expect that a prion disease ASO would be dosed intrathecally, meaning via a lumbar puncture. If that sounds scary, it’s not — as Sonia will tell you, she’s undergone four lumbar punctures for research and found it to be no big deal.

the case for lowering PrP

Our interest in ASOs stems from the excellent proofs of concept that lowering PrP should be both a safe and effective strategy against prion disease.

It is known for certain that PrP is the cause of prion disease. This knowledge is the culmination of decades of research and every line of evidence is in agreement — below is a table Sonia and I have put together summarizing just a fraction of the data.

| category | evidence |

|---|---|

| biochemical | • Prions, the infectious agent in prion disease, are composed of PrP [Prusiner 1984, Prusiner 1998]. • Prion “strains” are encoded in distinct conformations of PrP [Bessen 1995, Telling 1996, Safar 1998]. • Prion infectivity can be generated in vitro from bacterially expressed recombinant PrP [Legname 2004, Wang 2010]. |

| animal genetics | • PrP is required for prion neurotoxicity [Brandner 1996]. • PrP is required for prion propagation [Bueler 1993, Prusiner 1993, Manson 1994, Sakaguchi 1995]. • PrP dosage and incubation time are inversely correlated [Bueler 1994, Fischer 1996]. • PrP amino acid sequence governs the “species barrier” [Scott 1989, Telling 1994]. |

| human genetics | • Protein-altering variants in PRNP segregate with genetic prion disease [Hsiao 1989, Hsiao 1991]. • Some missense variants in PRNP confer protection against prion disease [Palmer 1991, Shibuya 1998, Mead 2009]. • PRNP is the primary or only locus to exhibit genome-wide significant association to prion disease risk [Mead 2012]. |

Evidence that PrP causes prion disease.

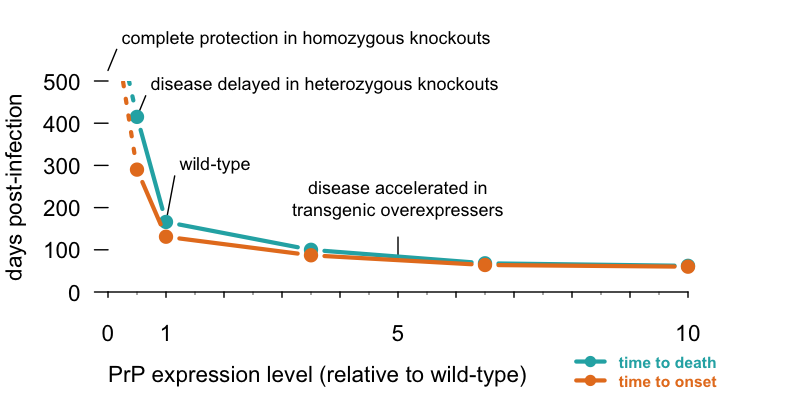

Particularly compelling is the dose-responsive curve relating PrP abundance to the pace of disease in mice. When mice are intracerebrally infected with prions, they develop prion disease after a very predictable number of days that is tightly related to how much PrP they produce. Below I have re-plotted a classic set of data from [Fischer 1996] showing this relationship.

The less PrP, the better, and the more PrP, the worse. Time to disease and terminal illness in mice intracerebrally infected with RML prions, adapted from Table 1 of [Fischer 1996]. Homozygous PrP knockout mice can neither propagate prions nor suffer from prion disease, heterozygous knockouts take >2x as long as wild-type mice to get sick, and transgenic overexpressers get sick faster. Code to produce this plot.

This curve is important because it shows that the benefits of PrP lowering are dose-dependent. You don’t need to lower PrP to zero in order to delay prion disease — every bit helps.

The mice in the above curve are constitutively genetically modified to produce more or less PrP for their whole lives. But the benefits of PrP lowering are not exclusive to lifelong reduction. Two compelling proof-of-concept studies have shown that lowering PrP even after prion disease begins can be highly beneficial. In one study, Cre recombinase was used to excise a Prnp transgene in neurons several weeks after mice were infected with prions, and the mice were protected from disease out to at least 400 days [Mallucci 2003]. In another study, a Tet-off switch was used to turn PrP expression down to 20% of normal levels 100 days after mice were infected with prions, and the mice lived nearly 3 times as long as untreated controls [Safar 2005]. In addition, a clever experiment grafting wild-type (PrP-expressing) tissue into a PrP knockout mouse showed that even when prions are all around, PrP knockout neurons are unaffected [Brandner 1996]. In other words, prion neurotoxicity is cell autonomous and requires PrP expression. This, together with the conditional knockout/knockdown studies, makes it conceivable that a PrP lowering drug might be able to slow down progression of prion disease even in the neurotoxic phase of disease.

PrP knockout animals. From left to right: a mouse from Wikipedia (I couldn’t find a photo of an actual PrP knockout mouse); PrP knockout cow from [Richt 2007]; naturally occurring PrP knockout goat from [Reiten 2017; and hypothetical human. We haven’t found any homozygous knockout humans, but individuals with heterozygous loss-of-function mutaitons are healthy.

Meanwhile, as Sonia explained in her post, we have ample evidence to suggest that PrP lowering should be safe. The only confidently identified phenotype of PrP knockout mice is an age-dependent defect in myelin maintenance on peripheral nerves, resulting in a mild peripheral neuropathy [Bremer 2010]. It’s not seen the central nervous system (CNS), and the receptor, Adgrg6, involved in this pathway is not even expressed in the CNS [Kuffer & Lakkaraju 2016]. And the myelin maintenance defect is not seen in heterozygous knockout mice, only complete knockouts [Bremer 2010]. Consider that a PrP-lowering drug might lower PrP by half if we are lucky — no currently available technology is going to lower PrP to zero. Knockout cows and goats are also reported to be healthy [Richt 2007, Yu 2009, Benestad 2012], and the few humans we have been able to identify with heterozygous loss-of-function mutations in PRNP are healthy as well [Minikel 2016]. All together, this is a compelling body of evidence that lowering PrP should be safe, though of course, safety can never be assumed — any new drug will always be tested first in a Phase I clinical trial where a small number of individuals start receiving small doses of the drug under very close medical monitoring.

If you’re still worried about knockout phenotypes, remember that almost every drug that humans take targets one protein or another in the body, and many of those targets have important native functions and are highly essential and strongly conserved across evolution. For example, cholesterol-lowering statin drugs are inhibitors of HMG CoA reductase and have saved millions of lives, even though knockout of that enzyme is embryonic lethal in mice [Ohashi 2003]. Even aspirin targets the product of a gene, PTGS2, where loss-of-function mutations are strongly selected-against in the human populaton. In general, there is a big difference between targeting a gene with a drug versus with a genetic manipulation. Constitutive genetic knockout means total lack of the protein in every cell of the body for the organism’s entire life. Most drugs achieve only incomplete inhibition, are reversible and adjustable based on dose, might reach only some tissues and not others, and might be taken only by people for whom the risk-benefit calculus is favorable.

For prion disease, a non-allele-specific knockdown strategy makes sense. As the above data show, lowering all PrP should be beneficial, and there is not much reason to be worried about on-target side effects. Non-allele-specific means it should be possible to develop one drug for all types of prion disease including the >60 different mutations, as well as sporadic and iatrogenic disease, where there is no mutation. Even in individuals who do have a mutation, sometimes the wild-type allele can also form prions and presumably contribute to disease. Finally, it should be possible to design safer and more potent ASO sequences without the constraint of needing to overlap a mutation site.

the promise of antisense oligonucleotides

ASOs have been around for decades, and from the beginning, there were people saying that they “promise to open up a new era of drug research with the possibility of rational drug design based on the nucleotide sequences of the genes causing the disease” [Uhlmann & Peyman 1990]. But realizing this promise has taken time. The past few decades have witnessed a tremendous breadth and depth of basic research into how ASOs work and how to make them work better. This series of blog posts will cover only a tiny fraction of this body of literature. Even just a few years ago, when the Prusiner lab published the first study of antisense oligos as potential therapeutics for prion disease [Nazor Friberg 2012], it wasn’t yet clear how promising this area was, and many questions remained unanswered. There exist ASO drugs approved or in human trials for a range of different conditions including muscle disease, liver disease, and cancer, but I will focus this post on brain diseases, because developing drugs for the brain is a special challenge.

There are, in principle, multiple ways you could try to lower the levels of one target protein in the brain, and many of these methods have been attempted for prion disease. Small molecules are exciting because with careful medicinal chemistry they can sometimes be made to cross the blood-brain barrier, and there has been some interesting early-stage work on this front [Silber 2014]. But discovering safe and bioactive small molecules is a long road, and it is especially difficult to find ones that very specifically lower one protein and don’t just throw a wrench into the biosynthesis of a whole swath of different proteins. RNA interference is a more targeted approach, but it has the disadvantage that it needs to be “vectored” — the siRNA has to be packaged in a virus to reach brain cells, and the viruses do not distribute well throughout the brain. A study of virally vectored RNAi therapy in prion-infected mice found that the virus was only able to reach a small region of the brain around the injection site [White 2008].

As recently as a few years ago, ASOs were still being delivered to the brain, both in mice and in humans, by intracerebral pumps to provide a continuous infusion of drug [Smith 2006, Miller 2013]. A critical turning point in the development of ASOs for neurological disease came in what appears at first glance as a routine pharmacology study [Rigo 2014]. Ionis Pharmaceuticals was characterizing the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a drug candidate for spinal muscular atrophy, and they discovered that the compound was actually more potent in rodents when it was given in bolus dosing — one big single injection — as opposed to continuous infusion pump-based dosing. They then went on to do bolus doses intrathecally (via lumbar puncture) in monkeys, and found that the ASO reached not only the spinal cord but distributed widely throughout the brain. The ASO’s half life was more than 2 months in the brain and several months in the spinal cord, offering the prospect that occasional lumbar punctures might be enough to provide a sustained therapeutic benefit in a human.

In December 2016, that ASO, now known as nusinersen, became an FDA-approved drug for spinal muscular atrophy, and the first disease-modifying therapeutic for any neurodegenerative disease. It has proven remarkably safe and effective at arresting disease progression in affected children [Chiriboga 2016, Finkel 2016, Finkel 2017], and the preliminary reports from prevention trials are that children who get the drug before symptoms are developing normally. It’s a remarkable result for a disease that was so deadly and so utterly without any treatment for the underlying disease process just a few years ago.

On the heels of that success, several other ASO drug candidates for brain disease now in clinical trials, including against tau (MAPT) for Alzheimer’s and frontotemporal dementia, against SOD1 for ALS, and against huntingtin (HTT) for Huntington’s disease (see Ionis’s pipeline).

As discussed in this post, nusinersen is actually a splice-modulating ASO that needs to do its work mostly in the spinal cord, so it is not a perfect proof of principle for prion disease, where we would want an RNA-lowering ASO to work in the brain. But nusinersen does reach the brain [Finkel 2016], and data from non-human primate studies also demonstrate that ASOs can distribute broadly throughout the brain and lower their targets potently [Kordasiewicz 2012, Devos 2017].

The Phase I/II data from the Huntington’s disease trial were announced a few months ago — I have reviewed them in detail here. Like prion disease, Huntington’s disease is a monogenic, adult onset neurodegenerative disease of the brain. While we still don’t know if the HTT ASO was effective at slowing disease progression — testing that will take a years-long pivotal trial — what we know is that the ASO was well-tolerated, with no serious adverse events in the treatment group, and it lowered mutant huntingtin in cerebrospinal fluid by 40%.

As explained above, there is ample reason to believe that if we could lower prion protein by 40%, that would have a huge impact on prion disease. And ASO drugs are modular: plus or minus a few chemical modifications, they are all basically the same four building blocks — the same A, C, G, and T nucleotides that make up our DNA — stitched together in a different order to target a different gene sequence. So if a 40% knockdown can be achieved for huntingtin, there is no reason in principle why it couldn’t be achieved for prion protein. That doesn’t mean that success is by any means guaranteed — drug development is always difficult, without exception. But it does mean that ASOs are a very promising place to look for a prion disease drug.

conclusion

As Sonia explained in her post, there is a lot of science that we need to do in the lab, and also a lot that we as a prion disease community need to do to get ready for clinical trials of ASOs down the road. We’ve been incredibly busy with all this, hence my radio silence on this blog for the past six months. But for me, it’s also important to make time to read papers, sift through the science and make sure I understand the principles behind what we’re doing. So over the coming weeks, you can look forward to seeing the rest of this blog post series on the science of ASOs.