Racing against a clock we can't see

We need to develop a drug to prevent prion disease before it strikes, but we can’t predict when it will strike.

I’m proud to announce that as of last week, our new study on age of onset in genetic prion disease is now available on bioRxiv [Minikel 2018] (update: final published version is [Minikel 2019]). The public dataset and source code for the study are in a public GitHub repository.

motivation

A few years ago, we published a study trying to answer the first question we asked after getting our genetic test report: does this mean I’ll definitely get the disease? This new study has its origins in our second question: when?

From the moment Sonia received her predictive genetic test report, we wanted to know how long we had before disease would strike. From the reviews that we read [Kong 2004, Mastrianni 2010], it was clear that even with the same mutation, there were some unlucky people who got the disease in their 20s and others who made it to their 70s. We asked whether anything might affect age of onset, and we were at various times counseled — with no basis in evidence, we now realize — that Sonia’s mom’s age of onset was predictive for Sonia’s own fate, or that Sonia’s PRNP codon 129 genotype might be protective. The more we dug into the literature, the more we realized the answers we were looking for weren’t out there. So, with the help of many collaborators, we launched a research project to see what we could find. Our colleagues in the prion field stepped up and, incredibly generously, spent countless hours collating records from decades of prion surveillance and clinical programs to find the data we needed.

age of onset in genetic prion disease

We and our collaborators first started gathering age of onset data for a study several years ago, where we showed that age of onset does not change over generations [Minikel 2014]. We then spent almost another four years collecting more data and cleaning and analyzing it. As our sample size reached the high hundreds and topped out at just over a thousand individuals, two things became clear.

First, age of onset is even more variable than we had realized. For example, for Sonia’s mutation, D178N, there has been a case with onset at age 12 and one individual who lived to 89 without developing disease.

Second, we were not finding any factors that helped to predict an individual’s age of onset. Neither your sex, nor your parent’s age of onset, nor your PRNP codon 129 genotype were proving to have any predictive value in the overall dataset.

Of course, it’s possible that with a larger sample size we could find predictive factors. But genetic prion disease is rare, and it is likely that our dataset already includes perhaps half or more of the people ever successfully diagnosed, meaning that it will be a long time before we have a much larger dataset. Long story short: age of onset varies over several decades, and as far as we can tell today, it is totally random. As Sonia often says in talks, we are racing against a clock we can’t see.

what does this mean for mutation carriers?

This analysis has implications for how we as people at risk think about that risk. For example, we now know that Sonia’s mom’s age of onset — 51 — does not have special significance for us. Likewise, knowing the average age of onset for a given mutation still does not do much to predict when a given individual will have onset. It turns out that when we say that some PRNP mutations are highly penetrant, we’re not saying, “You will get to a certain age and then definitely develop prion disease.” What we mean instead is “you have a low risk of onset in any given year of life, but there are decades over which the disease could strike, and so in the aggregate, it’s very likely that you’ll eventually develop the disease.”

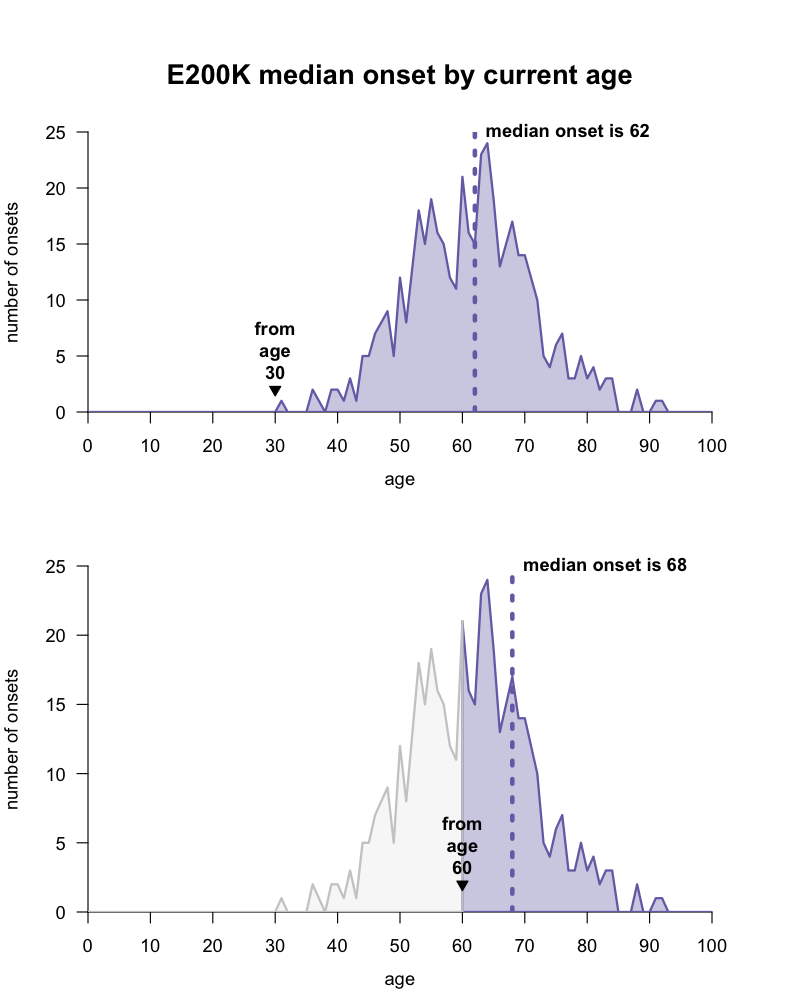

This gives rise to what seems at first like a paradox. Disease is very likely to strike at some point — we have multiple lines of evidence that some PRNP mutations confer high lifetime risk [Minikel 2016] — yet almost no matter what age someone is, their disease onset is on average always years away. Take for example the most common mutation, E200K. As a disclaimer, our dataset is imperfect, and remember that we can’t predict any individual’s age of onset, instead we can only speak in terms of group averages. According to the data we have today, for a group of people at age 30, the median age of onset will be about 62, but for a group of people who have reached age 60, the median age of onset has now retreated to 68, because they were already lucky enough to avoid the early onsets that bring the average down.

There is a wide distribution of disease onsets for the PRNP E200K mutation, and the expected median age of onset for a group of people with this mutation depends on what age they are today. code, data.

This is great news for a mutation carrier at age 60, but it poses a challenge for preventive clinical trials.

what does this mean for trials?

We came to the realization that age of onset is highly variable and completely unpredictable just as the work we are doing to try to advance antisense oligos (ASOs) to the clinic as prion disease drugs led us to another question. How will we show that a drug works?

Our goal is to delay the onset of Sonia’s disease. If we are successful in finding a drug that does delay the onset of prion disease, how we will prove it?

Many people we spoke with wanted to point us to early treatment or prevention trials in Alzheimer’s disease as models for what we could try to do in prion disease. Some Alzheimer’s trials have recruited individuals who already had mild cognitive impairment, with the goal of halting their progression into dementia [Petersen 2003]. Others are “secondary” prevention trials based on ascertaining patients who are unimpaired but already have biomarker evidence of pathology, such as Aβ in their brains [Sperling 2014]. These approaches would be difficult in prion disease, because most subtypes have just a half-year disease course from first symptom to death, and to date, we don’t yet have any consistent evidence for changes in either imaging or fluid biomarkers before disease onset.

Instead we looked to “primary” prevention efforts, which aim to stop the disease process before it even starts. The Alzheimer’s Prevention Initiative (API) trial in Colombia has been enrolling healthy people with an early onset Alzheimer’s mutation (PSEN1 E280A), randomizing them to drug or placebo, and following them five years to a cognitive score endpoint [Tariot 2018]. In other words, it is a randomized trial with a clinical outcome — a measurement of how patients feel or function. That’s considered the gold standard of evidence for showing that a drug works.

We want a drug for prion disease, we want it to work, and we want to know that it works. But given what we had just learned about age of onset, we also had to ask whether we could afford to hold ourselves to this “gold standard”. So we asked: would it be mathematically feasible to take healthy presymptomatic people with PRNP mutations — people like Sonia — randomize them to drug or placeo, and learn in a reasonable window of time — say, five years — whether treated individuals have fewer disease onsets?

Estimated risk of onset within the next year (y axis) for genetic prion disease versus age (x axis) and number of individuals surviving to that age (line thickness). By the time annual risk is high, the number of surviving individuals is small. This poses a numerical challenge for randomized trials following people to disease onset, because in order to have statistical power to show that a drug works, such trials would require a large number of people at high annual risk.

We explored a variety of assumptions and statistical approaches, and you can read the paper for all the details. But long story short, this standard looks prohibitively difficult to achieve in prion disease under today’s conditions. Suppose for example that the drug works, and delays onset by 7 years on average. In order to have an 80% chance of a successful trial outcome, you would need N=813 people, age 40+, all with high risk PRNP mutations, to enroll in a 5-year randomized trial.

Those numbers should give us pause. There may actually exist that many mutation carriers in the U.S. — based on disease incidence we think that the true carrier rate for these mutations is on the order of 1 in 100,000 — but the vast majority don’t know they are at risk or haven’t been tested, and those that do get tested (and test positive) are likely to skew young [Owen 2014]. We certainly hope that the availability of a therapeutic will lead to more people learning their genetic status and seeking treatment. But a groundswell of interest in genetic testing is more likely to follow approval of a drug; we can’t necessarily count on it happening before a trial even starts. It’s a bit of a chicken and egg problem.

Thinking about who we could realistically recruit today, with trials hopefully on the horizon but no approved drug on the shelf, we called up Dr. Jiri Safar, then director of the U.S. prion surveillance center, which handles all the predictive genetic testing for PRNP in this country. He was able to share the fact that only N=221 asymptomatic people in the U.S. hold a positive predictive genetic test report like Sonia’s. Once you consider that many of these people are young and not every PRNP mutation is high-risk, we are very far from that aspirational 813.

Where does this leave us? The main insight for us has been that when we think about presymptomatic trials in genetic prion disease, we need to be creative. Proving that a drug is preventive by using a clinical endpoint in a randomized trial is not just difficult but maybe even impossible in genetic prion disease, at least under today’s conditions. We need to think about other ways to show that a drug can benefit healthy mutation carriers. One approach would be through a trial based on a biomarker: a laboratory test you can run on a living patient, to measure a change at the molecular level to see if a drug had its intended effect. This analysis gives us a mandate, as scientists, to characterize biomarkers, and work together with regulators to figure out how such a biomarker could be used in a presymptomatic trial. Over the much longer term, after a drug is already approved and on the market, there could be opportunities to measure by how much it delayed onset by following the people on the drug for many years, and in the paper we provide some assessment of how this might be achieved.

conclusion

At the end of the day, what we want is a drug that delays onset of genetic prion disease. It’s possible that such a drug would also be effective in symptomatic patients. That would be a fantastic outcome and would also make it easy to get the drug approved. But the worry is, what if you find a drug that can delay or prevent prion disease but that just doesn’t work once patients are sick? There are plenty of examples from other diseases where prevention and treatment aren’t the same thing. Cholesterol-lowering drugs, such as statins, can save you from a heart attack if you take them a decade in advance, but they aren’t much use at the moment you are admitted to the emergency room having a heart attack. And there are preclinical examples of this in prion disease. IND24 quadrupled the lifespan of prion-infected mice when given prophylactically but if you waited until a few months post-infection (even before symptoms), it had no effect at all [Giles 2015]. Sonia and I can’t afford the risk that a preventive drug fails to win approval because we pin all our hopes on efficacy in a symptomatic trial.

We need a route forward for testing drugs in healthy, presymptomatic people, with the goal of delaying onset. Our new study shows that to achieve this, we cannot rely on a conventional model of randomizing people to a clinical endpoint. Instead, we must rely on biomarkers that can give us a molecular readout of a drug’s effect. This mandate has already begun to shape our work in profound ways — motivating, for example, our ongoing clinical study at Mass General Hospital, our study of cerebrospinal fluid prion protein as a biomarker [Vallabh 2018], and our effort to understand all the other biomarker efforts ongoing in prion disease. By publishing this study, we hope this realization will help to shape others’ work as well.

I want to give a huge thanks to all the collaborators who contributed data to this study — this was a tremendous collaborative effort and I owe a huge debt of gratitude to everyone who contributed. I also want to thank all the genetic prion disease patients and families who gave their data to this study. Your research participation is critical for our ability to develop a drug, and we are immensely grateful for your contributions.