ASOs work

introduction

Sonia and I have been working with Ionis Pharmaceuticals to advance antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) to lower prion protein in the brain as a drug for prion disease. In the time since we announced this project publicly a couple of years ago, I’ve blogged about what ASOs are, how they work, their chemical composition, distribution in the body and in cells, and safety profile. I’ve shared how our biomarker development projects and MGH clinical study tie into this drug development project, and how we’ve interfaced with regulators to chart a path for clinical trials. In this post, I’ll share the large body of evidence we’ve now amassed from our studies of ASOs in mice. We set out to ask whether ASOs work against prion disease, as well as how well they work, how they work, when they work, against what prion strains they work, and what outcomes they change for the mice.

The short answer is the title of this post: ASOs work.

More specifically:

- ASOs are effective against prion disease.

- They work by lowering PrP.

- They are effective in proportion to how much they lower PrP.

- They work against multiple prion strains.

- If administered early and often, they are as good as knocking out one allele of the PrP gene.

- If administered later on, they can still extend survival and affect disease-relevant biomarkers.

All this we’ve learned from a large battery of mouse experiments conducted both in our lab at the Broad Institute, as well as by collaborators at NIAID Rocky Mountain Labs (Byron Caughey’s lab) and McLaughlin Research Institute (Deborah Cabin’s lab), presented in one paper published last year [Raymond 2019] and another just pre-printed this week [Minikel 2020].

We believe that the evidence that now supports advancing ASOs into clinical trials is strong. Stronger than we’ve seen for any other therapeutic concept in prion disease that has come and gone in the eight years we’ve been at this. First and foremost, the data are just good — and that’s what I’ll spend most of this post on. In addition, the replication across three independent study sites lends a special credibility to our findings. We have sought to elevate our studies in terms of rigor and openness: in all but the first study we did at the Broad, all animal assessments were undertaken by technicians blinded to the animals’ treatment status, and we have made athe raw, individual-level animal data available in public GitHub repositories (aso_survival and prp_lowering). Importantly, the project has legs: Ionis Pharmaceuticals has publicly committed to developing an ASO drug for prion disease. Finally, to whatever extent that studies in mice can bear on studies in humans, I think the data lend optimism about the prospects for clinical development of ASOs, a topic I’ll circle back to at the end.

ASOs work

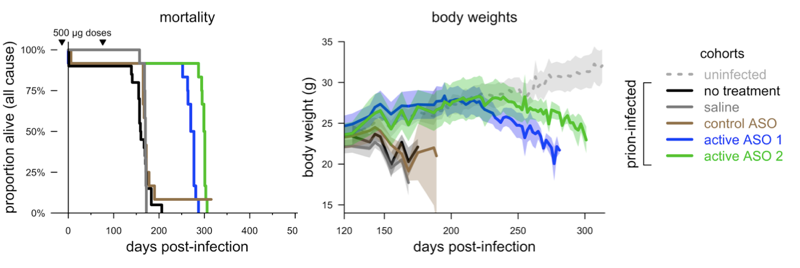

Here is the survival curve from the first mouse study that Sonia and I ever did:

Adapted from [Raymond 2019] Figure 2.

We infected mice with prions, gave them 2 doses of ASO — one prophylactic and one follow-up dose — and they lived 61-76% longer than controls. And as far as we can tell, it was an extension of healthy life, as the mice maintained body weights on par with uninfected animals well past the point where controls died. At the same time that we were doing this, Byron Caughey’s lab did a similar study with a very similar result:

Adapted from [Raymond 2019] Figure 2.

Here, with 3 smaller doses, they extended survival by 81-98%. And again, the onset of disease, as defined by observation of symptoms, was likewise delayed, while the progression from onset to death was about the same regardless of treatment — healthy life was extended.

How ASOs work

When we first met with Ionis scientists in 2014 to launch this project, one of the things they most wanted to see was evidence as to how their drugs worked against prion disease — what was the mechanism of action. Years earlier, they had previously collaborated with the Prusiner lab at UCSF, and so they already had some idea that ASOs worked [Nazor Friberg 2012]. But they had also seen evidence that ASOs, which are designed to bind RNA, also happened to bind prion protein itself [Kocisko 2006, Karpuj 2007, Nazor Friberg 2012]. If this direct binding of the protein contributed to the efficacy of ASOs, that could make drug development complicated in all sorts of ways.

But what we saw in the above studies is that only ASOs that have a sequence that is antisense to the PrP gene, and that lower PrP, are effective in mice. You can see that both we and Byron Caughey’s lab included a control ASO (in brown) that does not target PrP RNA, and it didn’t extend survival at all. Soon after, we replicated this finding with a new set of ASOs, of a different chemical composition, that Ionis sent us:

Adapted from [Minikel 2020] Figure 1.

Once again, the ASO that wasn’t designed to bind PrP RNA, and didn’t lower PrP, did nothing.

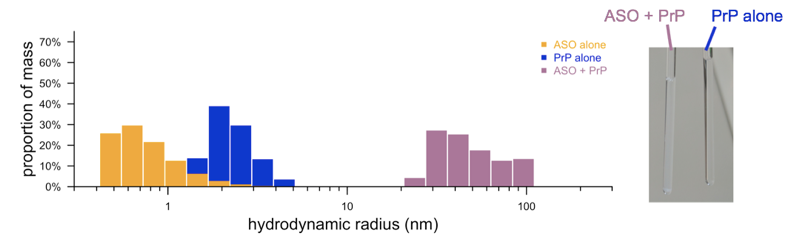

Why? We found it preplexing that there was so much evidence that ASOs bind PrP in vitro and in cell culture and yet that this didn’t seem to do anything in vivo. We launched a whole series of in vitro studies to understand the interaction between ASOs and PrP [Reidenbach & Minikel 2019]. We confirmed that all the ASOs we were studying did bind PrP, and that the affinity was similar between our ASOs that did versus didn’t work in vivo, as well as one of the ASOs the Prusiner lab had studied. But we also saw that when high concentrations of ASOs and PrP were mixed, they aggregated into big clumps, which we could characterize by various biophysical techniques but which we could also see with the naked eye — notice how the solution at right is cloudy:

Adapted from [Reidenbach & Minikel 2019 Figure 2.

Aggregation is often a source of misleading results in in vitro and cell culture assays. Compounds that aggregate or cause aggregation can often be “false positives” at least in some sense — which isn’t to say they necessarily do nothing, but just that their activity is highly dependent on conditions in a way that makes them a lot less likely to translate from an in vitro system into in vivo. Indeed, we found that just upping the salt concentration to physiological conditions decreased the strength of the “binding” quite a bit. That doesn’t mean that everything ever published about ASOs interacting with PrP is wrong — in fact, it’s pretty clear that in cell culture, the direct binding of the protein does do something real. And in fact, Byron Caughey’s lab showed years ago that, in animals peripherally infected with prions (the infection is introduced outside of the brain rather than directly into the brain), prophylactic doses of random oligo, not targeted to PrP RNA, could extend survival substantially [Kocisko 2006]. But when prions are in the brain, this does not seem to be the case. It could just be that conditions at the cell surface are different in the brain, and/or, it could just be pharmacokinetics: when ASOs are dosed periodically into cerebrospinal fluid, their concentration quickly drops below the nanomolar levels required for ASO-PrP binding. In any case, we’ve convinced ourselves and Ionis that the ASO-PrP binding is not a factor in how ASOs are effective in vivo, and that greatly simplifies their process of designing the drug and our process of thinking about how a biomarker could read out the drug’s effect.

Dose-response

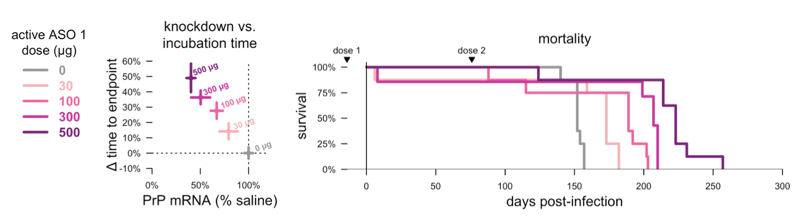

We knew going in, from heterozygous knockout animals. that lowering PrP by 50% is enough to more than double survival time after prion infection [Bueler 1994]. But we often got the question, how much do you need to lower PrP to be successful? Is there some “threshold to effect”? To try to answer this question we did a dose-response experiment:

Adapted from [Minikel 2020] Figure 2.

Even the lowest dose, which achieved just 21% knockdown, gave us a 15% increase in survival time. But survival time moved in lockstep with PrP lowering as we went to higher and higher doses. This is important because, as we think about CSF PrP as surrogate biomarker endpoint for clinical trials in prion disease, we will want to know how much we need to lower it in order to believe that we’ve impacted disease. Overall we think there are two take-homes here:

- Lowering PrP by any amount is good

- Lowering PrP by more is better

Strains

Prion strains have been the stumbling block of some of the most promising antiprion compounds previously invented. The Prusiner lab’s IND24 succeeded spectacularly against mouse RML prions but did nothing against human prions [Berry 2013]. Thus, figuring out if PrP-lowering ASOs work against multiple prion strains was particularly important to us. We haven’t yet had the opportunity to evaluate ASOs against human prions in humanized mice, but we did evaluate five different mouse prion strains.

We saw efficacy against five out of five prion strains tested [Minikel 2020]. The ASOs worked if given early, and they also still worked later on, though it was more complicated, with not all animals benefitting. In the ASO studies, we didn’t see any big differences between strains. We also studied the course of prion disease from these five different strains in heterozygous knockout animals. Here, there appeared to be some difference of degree, but no difference of kind: heterozygous knockout was quite effective against some strains (increasing survival at least +63%) and wildly effective against others (increasing survival up to +163%), but overall, it was effective against all five prion strains. In one study, we also infected animals with prions from animals that had been treated with ASOs, to see if drug resistance had developed — but the ASOs still worked, so we did not see any evidence of drug resistance. Thus, just as we expected since PrP is the constituent of all prions regardless of strain, lowering PrP appears so far to be a universal strategy against prions.

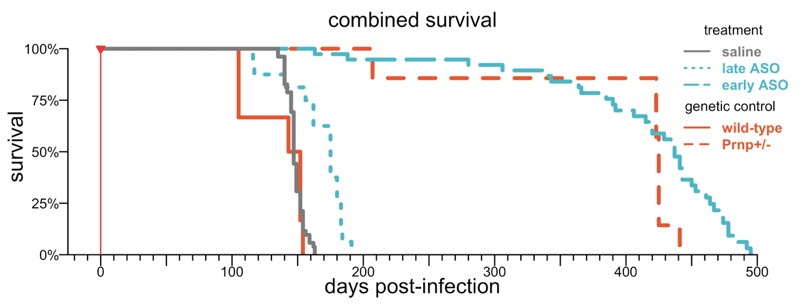

Early chronic treatment

In most of the studies above, we gave two doses of ASO. In the clinic, we expect that people would get a dose every few months, indefinitely. Presumably, keeping PrP low by dosing over and over is better than just lowering it transiently. We did a chronic dosing study to examine the limit of ASO efficacy with indefinite dosing, and to ask how late in progression towards disease the dosing could be initiated. We found that as long as ASO treatment was started early enough — anytime up to 78 dpi, around when early neuropathology becomes detectable, we could basically replicate the effect of heterozygous knockout, delaying disease by 3-fold (“early ASO” curve):

Adapted from [Minikel 2020] Figure 5.

We also tried waiting longer, until 105 or 120 dpi (“late ASO” above), when neuropathology is prominent and symptoms may — depending on who you ask and what you measure, or even which mouse you test — be setting in. At these timepoints, in this particular study, we could only delay disease by about 19%. But the result in these later treatment studies turns out to depends a lot on what you measure and how long you follow the mice.

Late treatment

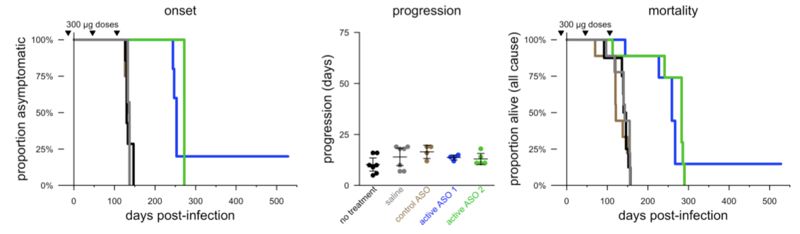

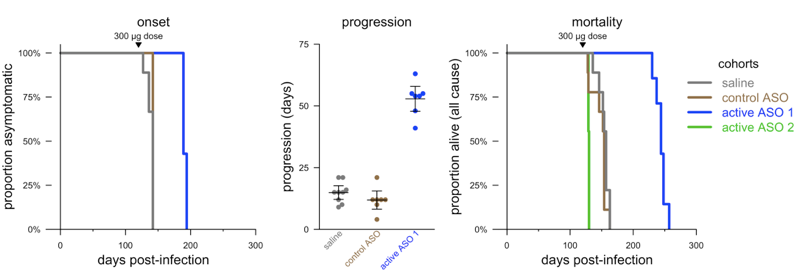

In fact, our first glimpse of how ASOs can work later in prion disease came from an experiment Byron Caughey’s lab did very early on. They gave mice a single dose of ASO at 120 days post-infection, a timepoint when, in their hands, the mice are just a couple weeks away from obvious symptoms. Here’s what they saw:

Adapted from [Raymond 2019] Figure 3.

Again, they saw efficacy — ASO 1 extended the time to terminal disease by about 55%. Some of that efficacy came from delaying onset (+33%) while some came from slowing the symptomatic course of disease (~3x). We later did a nearly identical experiment at Broad, but with a different set of ASOs, and got almost the exact same result [Minikel 2020], again following the mice to terminal disease, which was delayed 68%. But in the study described in the previous section, where we followed mice to an endpoint of having five prion disease symptoms, we only delayed that endpoint by 19%. As far as we can tell, both are true: late intervention may delay symptoms, or slow the accumulation of early symptoms, by a bit, while it may also slow the progression from early symptoms to terminal disease by a more dramatic amount.

An aside — at this 120 day timepoint, Byron’s lab also found that ASO 2 was not tolerated at all (green curve above). Indeed, the ASOs used in our mice are all just tool compounds that did not go through nearly the level of optimization and toxicology testing that a clinical drug candidate goes through. Several of these tool compounds have tolerability issues when the mice are in a neuropathological stage of prion disease, which is a limitation in many of our studies.

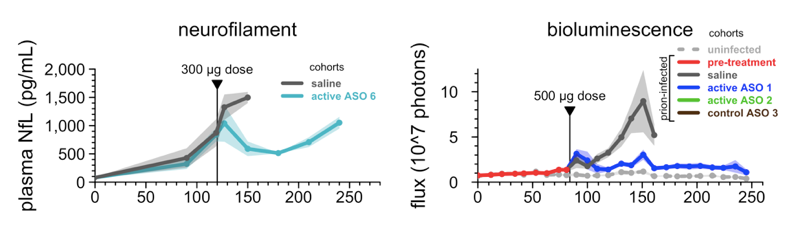

Our collaborator Deborah Cabin at McLaughlin Research Institute also conducted two studies in which she infected mice with prions, waited for a marker of neuropathology to rise, and then treated the mice with one dose of ASO. We were thrilled to see that it is possible to wait until you see neuronal damage, measured by plasma NfL levels, or astrocytosis, measured through live animal imaging, treat with ASO, and actually bring those markers back down:

Adapted from [Minikel 2020] Figure 4.

All of these “late” timepoints, though, precede the development of what I would call obvious symptoms. I have looked in many cages of prion-infected mice at 120 days post-infection, and they generally look pretty normal. Occasionally I could point to reduced nest-building or lethargy and say, “are those mice getting sick?” but rarely could I be sure. Indeed, Dr. Cabin led a natural history study of these mice (included in our paper [Minikel 2020] but a topic for a future post) and, long story short, 120 days is right on the cusp of when, group-wise, you can just barely start to show statistical differences between infected and uninfected animals, but it doesn’t mean that every animal is sick, nor that the illness is clear and unambiguous. So what if we treat even later, when the animals are clearly sick?

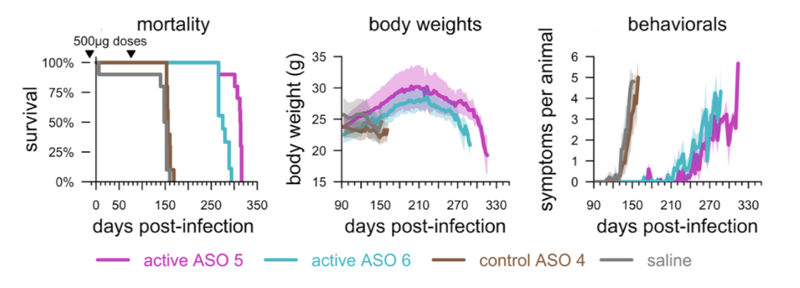

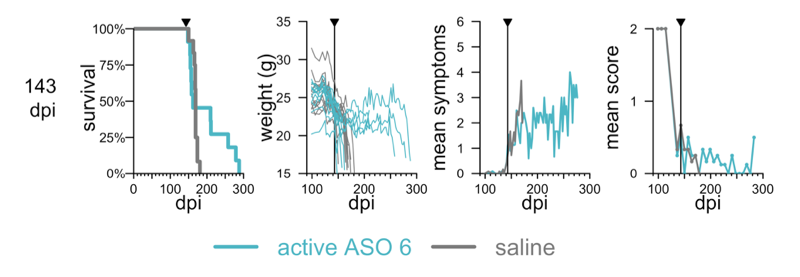

We treated animals at timepoints of 120, 132, 143, and 156 days post-infection, and followed them to terminal disease. Even at 143 dpi, when every individual animal had begun to lose weight compared to its personal peak, we saw at least some efficacy:

Adapted from [Minikel 2020] Figure 6.

At this stage, not every mouse benefitted. But you can see a hump in the survival curve — a minority of mice lived much longer than controls. People who study other diseases might at first glance dismiss this as “post-hockery” — after all, one can always concoct some weak yet true statement like “X% of mice lived longer than average”. But anyone who’s studied prion diseased mice knows that mice infected with this dose of prions simply are not going to be alive after 200 days unless a therapeutic worked. The standard deviation on endpoint in controls is 7 days, and the mice that outlived the controls outlived them by 85 days. Thus, our interpretation is that while some mice may have suffered from the poor tolerability of the ASO and/or were sick enough to hit their weight loss endpoint before the ASO kicked in, the ASO actually had a substantial effect on survival when it had time to kick in. It did not, unfortunately, reverse weight loss or symptoms or loss of nest-building, and when we tried dosing even later, at 156 dpi, ASO treatment did nothing. So there is such a thing as being too late to do any good, but in principle, PrP lowering can extend survival even at a frankly symptomatic disease stage.

conclusions

When we first got into prion research, we thought the most promising things out there were the antiprion small molecules discovered in cell culture phenotypic screens. But of the four chemical series being explored back then — 2-aminothiazoles, arylamides, cpd-b, and anle138b — none have been advanced clinically for prion disease. (Anle138b is now in a Phase I trial in healthy volunteers, NCT04208152, but is being developed for multiple system atrophy and not PrP prion disease). In the post-mortem, I think most researchers would argue that the main roadblock was strain specificity: all four series turned out to be effective against mouse but not human prion strains [Berry 2013, Lu & Giles 2013, Giles 2015, Giles 2016].

But I want to argue that these compounds actually had another roadblock ahead of them too: the lack of a well-supported path for clinical development in prion disease. Imagine an alternate universe where IND24 had turned out to work against human prions in humanized mice. One could try to test it in symptomatic prion disease patients, but this would truly be a Hail Mary, because, in mice, IND24 loses its efficacy around 90 days post-infection, well before the onset of first symptoms [Giles 2015]. Sure, mice aren’t humans, and things that work in mice often fail in humans, but, the cynic in me says that things that fail in mice don’t often turn out to work in humans. Alternatively, one could try treating pre-symptomatic individuals at risk for prion disease. This is well-supported by the in vivo data, as IND24, after all, could quadruple survival time in prion-infected mice if given prophylactically [Giles 2015]. But then what on Earth do you measure to figure out whether the drug worked? It’s numerically impractical to randomize pre-symptomatic people all the way to symptom onset [Minikel 2019]. IND24 does impact neuropathological markers such as NfL [Hirouchi 2019], which is promising. But practically speaking, the data so far suggest that, cross-sectionally, not many pre-symptomatic mutation carriers are in a prodromal neuropathological state at any given time [Vallabh 2019]. Too few, probably, for a neuropathological biomarker to be the sole basis for a clinical trial today, though one could certainly play a supporting role, and it is certainly worth further study to see if we can identify earlier markers.

Against this backdrop, I believe that the in vivo data we now have in hand provide a basis for two potential clinical paths for ASOs, or any other PrP-lowering drug, in prion disease. First, there is some potential for efficacy at a symptomatic disease stage. I take this with a lot of caveats because we don’t know how mouse timepoints relate to human timepoints and there is a risk of recruiting patients too late, when the drug may no longer be effective, or no longer be as effective as it could be. So treating sick patients shouldn’t be our only plan, but the in vivo data do suggest a possibility of efficacy. Moreover, the fact that ASOs can actually reverse neuropathological biomarkers could provide additional molecular readouts in such a trial. Second, PrP lowering is at its most effective in pre-symptomatic disease stages, before prominent neuropathology. Because most mutation carriers have normal biomarker profiles at any given time [Vallabh 2019], we have a real opportunity in the clinic to intercept at-risk people at a stage before neuropathology has set in. In this population, CSF PrP could be used to read out the effect of an ASO or other PrP-lowering drug, and all our in vivo data suggest that lowering PrP should dose-dependently predict a delay in disease, supporting the use of this biomarker as a surrogate primary endpoint. And if some fraction of these pre-symptomatic people do turn out to have elevated NfL or other prodromal biomarkers, a potential reversal of those markers could provide excellent supporting data as a secondary or exploratory endpoint.

Generating the data described above consumed a large fraction of the last three years of our lives. The reward is that, while PrP lowering was already a well-supported strategy, I now believe we have much more deeply validated this therapeutic hypothesis and established the parameters that govern its efficacy. While much work still lies ahead to get ASOs into clinical trials, I am more optimistic than ever about our prospects for a practical therapy for prion disease.