CJD Foundation Family Conference 2018

These are my notes from the CJD Foundation Family Conference, held at the Washington Court Hotel in Washington, D.C. July 12-16, 2018.

Robert G. Will - Keynote: Why do people get CJD?

When people lose a loved one to CJD, they always end up searching for an answer to one question: why did my loved one get this terrible disease? Dr. Will’s keynote today will seek to answer this question as best we can.

No one paid much attention to CJD until 50 years ago, when a seminal paper showed that the disease could be transmitted to chimpanzees [Gibbs 1968], thus suggesting that the cause of disease was a transmissible agent. Yet today we recognize that there are multiple different forms of prion disease that arise in different ways. According to the EuroCJD data, in Europe from 1993-2012, 88% of prion disease cases were sporadic, 8% were genetic, and only ~4% were acquired (iatrogenic CJD and variant CJD).

So what is sporadic CJD? Does it really arise spontaneously and randomly? Over the years, some people have hypothesized that there is an infectious origin to the disease, but the best scientific and epidemiological evidence provides no support for this idea. CJD has been reported in every country on earth that has bothered to establish any formal mechanism to look for it, meaning that if there is an infectious origin, then exposure to it has to be virtually universal worldwide. The incidence or frequency of CJD is pretty similar between all different European countries, meaning that the exposure would also have to be pretty uniform geographically. When we look at geographic distribution of CJD cases within one country, say, the U.K., we of course see clustering where there are population centers, but other than that, the distribution is random. There are instances where a number of cases have been identified in a small town [Collins 2002], which seems surprising at first, but when you consider how many small towns there are and the frequency of CJD, it is statistically inevitable that there will be some such instances just by chance [Klug 2009]. Similarly, given how often CJD occurs, it is not actually surprising that there has been one instance observed where a husband and wife both died of it [Brown 1998]. Extensive studies have failed to reveal any environmental risk factor for CJD [de Pedro Cuesta 2012], including that there appears to be no increased risk among health care workers and others who care for patients with CJD [Alcalde-Cabero 2012].

The frequency with which CJD is identified is rising steadily over time in every country that carries out surveillance. This is unlikely to be due to an increase in exposure to an infectious agent, because that increase would have to be so ubiquitous and uniformly rising everywhere, plus there is no evidence that these cases arise from exposure in the first place. Instead, it appears that two major factors contribute to the apparent increase in CJD cases: 1) aging populations meaning that a higher proportion of people are in the age range where CJD strikes, and 2) better diagnosis and reporting of CJD as surveillance networks have improved.

All told, we have no known environmental risk factors for CJD, no evidence for person-to-person spread, and no link to animal prion diseases nor to medical treatments, and the cases occur randomly in space and time. So how, then, does sporadic CJD arise? In 1995, Stanley Prusiner articulated what is now the consensus view in the prion field: that “at some point in the lives of the… individuals who acquire sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, cellular PrP may spontaneously convert to the scrapie form”. In other words, a spontaneous and random protein misfolding event triggers a misfolding cascade that spreads across the brain.

A smaller subset of prion disease cases are genetic, and it was shown nearly 30 years ago that they are linked to mutations in the prion protein gene, PRNP [Hsiao 1989]. A key question for affected families is how high is the penetrance — the probability that a person with a mutation will eventually develop the disease. It was recognized many years ago that there are some mutations that are clearly high-risk because so many people in the same family develop the disease, while there are other mutations that are more often observed in isolated cases. A study a few years ago was able to quantify the penetrance for individual mutations and show that some mutations confer a lifetime risk of only, say, 1% or 10%, while others cause close to a 100% risk of developing disease [Minikel 2016]. That said, there is still something random about when and whether people with a particular mutation will develop disease. For instance, there have been cases of identical twins with the same mutation where one develops disease and the other develops it much later or not at all [Hamasaki 1998, Webb 2009]. It would be very useful to know what causes such variability in age of onset.

Tragically, another form of prion disease is iatrogenic CJD, meaning, that transmitted by medical procedures [Brown 2012]. This has arisen through procedures such as dura mater grafts and cadaveric human growth hormone. Thankfully it now appears that the cases from these exposure incidents have leveled off and may even be over, but we have to remain vigilant to make sure this does not happen again.

Another form of prion disease is variant CJD, which emerged in the U.K. in the mid-1990s and was seen primarily in young people (age teens through thirties), in sharp contrast to sporadic CJD [Will 1996]. Overwhelming evidence argues that this disease arose from exposure to BSE-contaminated meat. We still don’t know why those affected were predominantly young. Dr. Will suspects it might have been some combination of difference in environmental exposure (young people ate more hamburgers and hot dogs) as well as age-dependent susceptibility. Luckily, like the iatrogenic CJD epidemic, the variant CJD epidemic now seems to be waning and maybe even over.

In spite of all the evidence that sporadic CJD is random and does not arise from infection, sometimes people still feel that a particular case or combination of cases is too weird, so weird that it cannot possibly be a coincidence. But Dr. Will told a personal anecdote of an incredibly bizarre coincidence and said that coincidences really do happen, and we should be careful not to overinterpret them.

Allison Kraus - Investigation of prion inactivation by reactive oxygen species in vivo

The alternate title of Dr. Kraus’s talk is “Can prions be stopped by a disinfectant naturally produced by the immune system?” She has been investigating the properties of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and a group of cells called neutrophils, which are considered the immune system’s first responders [Kobayashi & DeLeo 2009]. As a tool, she uses RT-QuIC, a prion detection assay [Wilham 2010] that uses the ability of misfolded prions to convert normal PrP into a fibril. Neutrophils fight pathogens by producing a number of different reactive oxygen species, including hypochlorous acid (HOCl). A couple of years ago, Dr. Byron Caughey’s lab showed that HOCl could be used as a prion disinfectant [Hughson & Race 2016].

Dr. Kraus mixed prions with neutrophils in a dish and found that the prions could stimulate the neutrophils to produce more ROS. She also used fluorescence labeling of the prions and the cell membranes and found that the neutrophils physically took up the prions. After this treatment, the amount of prion material in the dish was reduced, and this was particularly true when she used neutrophils with higher ROS production. The reduction in prions was shown by gel electrophoresis and also by RT-QuIC. Mouse studies are ongoing to see if the number of “infectious units” was also reduced. Dr. Kraus also looked at the brains of prion-infected mice and found that markers of HOCl-modified proteins are found in the same place as prion plaques are found, suggesting that HOCl naturally produced in the brain might be reacting with prions.

Hermann Altmeppen - Investigating the potential of the neuroprotective N1 fragment of the prion protein as a new treatment against prion diseases

The alternate title of Dr. Altmeppen’s talk is “Fighting prions with the prion protein”. For years it has been known that there are cleavage events, where a protease (a “molecular scissors” — a protein that cuts other proteins) will cut prion protein. One type is shedding, where almost the full-length protein is clipped off the cell surface — this was the topic of much of Dr. Altmeppen’s previous research and his previous CJD Foundation grant [Altmeppen 2011, Altmeppen 2012, Altmeppen 2013, Altmeppen 2015]. Another type is alpha cleavage, where the protein is cut in half, so that the structured half (called the C1 fragment) stays on the cell surface and the unstructured part (called the N1 fragment) is released from the cell. Several research groups have findings that in various ways suggest that alpha cleavage might be protective [Westergard 2011, Guillot-Sestier 2012]. There has also been some research to try to figure out what protease is responsible for alpha cleavage [Liang & Kong 2012] but we don’t have a complete picture yet, and Dr. Altmeppen thinks there may be multiple proteases involved.

Dr. Altmeppen wanted to figure out whether the N1 fragment released by alpha cleavage — the unstructured part of the prion protein that is released from the cell — might be protective against prion disease. To try to investigate this, he created a new line of transgenic mice that produce a lot of N1 fragment in addition to producing normal amounts of full-length prion protein. The hope was that the transgenic mice would live much longer than normal mice when infected with prions. However, the reality turned out to be that the disease progressed exactly as quickly in the transgenic mice as it did in normal mice.

Did this mean that the hypothesis that N1 was protective was wrong? To investigate further, Dr. Altmeppen took a closer look at how much N1 fragment is produced in the cells of his transgenic mice and where it ends up. When he ground up their brains, it looked like the transgenic mice produced a ton of N1 fragment. However, when he grew their cells in culture and just looked at the media (the liquid sitting on top of the cells) without grinding up the cells, he found that there was no extra N1 fragment produced. How can this be? Last year, a study showed that many unstructured or disordered proteins are very inefficiently transported out of the cell [Gonsberg 2017]. Therefore, it might be that Dr. Altmeppen’s mice produce a lot of N1 but it gets stuck inside the cell instead of getting exported outside of the cell, where the prion protein is. To overcome this problem, Dr. Altmeppen has now made a new transgenic mouse line that has N1 fused to a sort of carrier protein that will help it get exported properly from the cell. He hopes that this mouse will enable them to see whether the N1 fragment is really protective in the brain.

David A. Harris - Highly synergistic combination therapy for prion diseases

Dr. Harris received a CJD Foundation grant to study combination therapy for prion disease. As explained in his grant summary, his idea is that it might be effective to combine a drug targeting the replication of prions with a drug targeting the pathways that damage or kill nerve cells as a result. This builds on his previous work with a cell culture assay to discover antiprion compounds [Imberdis 2016] and is also using a cell culture model of prion neurotoxicity that his lab developed, where you can see prions causing neuronal synapses to collapse [Fang 2016].

Carole Crozet - Innovative human 3D neural network model for the efficient propagation of human prions

As reviewed previously on this blog, studying human prions in cell culture is a tremendous challenge. Dr. Richard Knight gave an introduction to Dr. Crozet’s talk in which he noted that when listening to talks about therapeutics, it is important to pay attention to what model system has been used for the study. Among cell culture studies, many studies are done by growing just neurons in a single 2-dimensional layer on the surface of a dish. He said he is excited about Dr. Crozet’s study because it is looking to create a more authentic model by growing brain cells in a 3-dimensional cluster containing many types of cells and not just neurons.

Dr. Crozet began with an introduction to what stem cells are. They are non-differentiated, non-specialized cells with two properties: they are self-renewing (they can divide into two identical cells) and can be differentiated (into more specialized cell types). Neural stem cells are just slightly more specialized than stem cells and are a precursor that can be turned into a variety of types of brain cells. While it is generally held that neurogenesis (the birth of new neurons) occurs only in very young animals and humans, there is some evidence that the adult brain does have a limited number of neural stem cells and that new neurons can sometimes develop in the adult brain too [Alvarez-Buylla & Lim 2004, Vescovi 2006].

One theory is that the growth of new neurons might be triggered in response to neuronal injury. Dr. Crozet’s laboratory has been able to identify adult neural stem cells in the brains of prion-infected mice, and they found that these cells propagated prions [Relano-Gines 2013, Relano-Gines 2014]. This is unfortunate in that it means that instead of being protective and restorative to the brain, these adult stem cells might actually have contributed to disease. However, on the plus side, it also presents an opportunity: maybe these cells could be used to build a better model of prion disease in a dish. Indeed, a study in the Alzheimer’s disease field found that they could use neural stem cells to create 3-dimensional cultures which developed a pathology in a dish much more similar to what is seen in Alzheimer’s brains, compared to conventional 2-dimensional cultures [Choi 2014].

Therefore, Dr. Crozet and Dr. Sylvain Lehmann set out to create a 3-dimensional culture model for prion disease using neural stem cells, with funding from CJD Foundation as well as the French ANSM agency. The hope is that by making these 3-D models from humanized mice — mice with the mouse prion protein gene deleted and the human prion protein gene added in — it might be possible to model human prions in cell culture.

Leonardo Cortez - Isolation and strain-specific characterization of pathogenic CJD prion particles

Dr. Cortez began with an introduction to the structure of misfolded prions. Prions form long, slightly twisted fibrils. We don’t know the structure at atomic resolution yet, but people have used electron microscopy to get a sense of the general shape of the prion fibrils [Sim & Caughey 2009, Vazquez-Fernandez 2016]. These studies used multiple different strains of rodent prions, but no one has done an analogous study on human prions yet. One challenge is that prion protein can misfold in more than one way, and form more than one shape. If you purify prions from the brain you will get multiple types of particles and it is hard to know which one or ones is/are the real culprit.

To be able to study CJD prions from human brain, Dr. Cortez developed a new biochemical protocol for purifying prions, and put them through a instrument that performs “asymmetric-flow field-flow fractionation” (AF4), which is a fancy way of separating microscopic or nanoscopic particles based on their size and shape and chemical properties. He is also using dynamic light scattering (DLS), which measures how particles floating around in water reflect light in order to gain information about the size and shape of the particles. So far, he has found that different strains of prions have different properties in terms of their fractionation outcomes, their particle size distribution, and their behavior in RT-QuIC, the prion detection assay mentioned earlier.

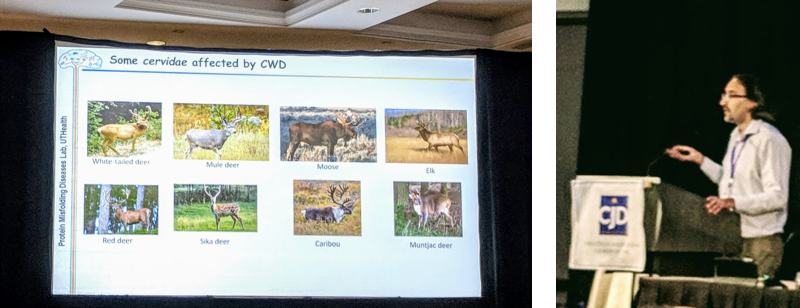

Rodrigo Morales - Systematic evaluation of the zoonotic potential of different CWD isolates

“Zoonosis” refers to diseases making the jump from animals to humans, as in the example of BSE in cattle becoming variant CJD in humans. Epidemiological studies, such as those Dr. Bob Will spoke about this morning, are one way of determining whether an animal disease might be transmissible to humans. There are also molecular approaches to look at whether an animal protein can convert a human protein to a different shape in a laboratory setting. Dr. Morales’s talk is about these types of approaches.

Dr. Morales began by reviewing chronic wasting disease (CWD), which is the term for prion disease in deer and elk. Deer and elk belong to a family called Cervidae, or cervids. CWD has been identified in many different wild species of cervids, and laboratory experiments have suggested that most or all cervids are susceptible.

Dr. Morales’s research makes use of a laboratory technique called protein misfolding cyclic amplification (PMCA). This technique uses brain homogenates and/or purified prion protein in a test tube to amplify prion infectivity in order to detect it. Last year they found that they could use PMCA to detect CWD prions in blood even before the animals are symptomatic [Kramm 2017]. Earlier studies had also found that proteins from one species can convert proteins from another species in PMCA, including for CWD [Castilla 2008, Barria 2011]. Dr. Morales’s current work studies whether common genetic changes found in the deer population affect the ability of the deer prions to cross the species barrier in order to convert human prion protein to the misfolded form.

Byron Caughey - Antisense oligonucleotides to delay or prevent the onset of prion disease in mice

Dr. Caughey received a CJD Foundation grant to study antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) as therapeutics for prion disease. He previously presented on this project at the CJD Foundation Family Conference in 2016 — you can see these slides from that presentation. At that time, he described the rationale for ASOs in prion disease (which Sonia also explained in this blog post), and he showed preliminary data demonstrating the development of ASOs that lower PrP RNA in the mouse brain by ~50%.

Dr. Caughey was not able to attend the conference in person this year, so he sent a short video set against a rustic Montana backdrop, providing some background and an update on the project. He explained that ASOs are a class of drugs that consist of short sequences of chemically modified DNA that can target a particular gene sequence in order to reduce the amount of one protein. Because prion disease is caused by one protein, PrP, it is possible to design ASOs to target and lower PrP, as a therapeutic for prion disease. He explained that the Prusiner lab previously did a small study on ASOs for prion disease [Nazor Friberg 2012], which generated some promising initial data but did not ultimately lead to a drug discovery effort. Sonia and I then met with Ionis Pharmaceuticals in 2014 to rekindle the project, and we kicked off a collaboration between Ionis, our lab at the Broad Institute, and Dr. Caughey’s lab at NIH. Ionis conducted a new screen to discover ASO molecules that lower PrP, and sent some of the most promising candidates to Dr. Caughey’s lab.

In the mouse studies in Dr. Caughey’s lab, the mice received microinjections of ASOs into the brain at 60-day intervals, though in humans, an ASO drug would be given by lumbar puncture into the base of the spine. In one study, ASOs were given in a few microinjections starting before the mice were infected with prions — this model might approximate the situation of people at risk for genetic prion disease getting treatment before the onset of symptoms. These mice lived ~70% longer than untreated mice. In another study, ASOs were given later in the disease course, shortly before the onset of symptoms; these studies are ongoing but the results look encouraging so far.

Dr. Caughey said he hopes to be able to give a full update on the results soon.

Sonia Vallabh & Eric Minikel - The path to an ASO drug for prion disease

Sonia opened by thanking CJD Foundation for the opportunity to speak about our work with Ionis Pharmaceuticals and Byron Caughey on the ASO project. She then briefly recapped our personal story — we lost Sonia’s mom to a rapidly progressive dementia in 2010, and learned after her death that it had been genetic prion disease. Sonia immediately made the decision to get tested and we learned in 2011 that she inherited her mom’s mutation. We changed careers to become scientists to work on developing a way to prevent her disease before it is too late. We are now PhD students in biology at Harvard Medical School and we are based at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, where we study therapeutics for prion disease.

Sonia explained that our personal goal is to delay or prevent onset of disease altogether. Her mother progressed from first subtle symptoms, recognizable only in hindsight, to profound dementia within about 6 weeks. We certainly hope that it will be possible to intercept people on this rapid decline. But, for those people like Sonia who know their genetic status years in advance, the greatest good we can aspire to do is delay onset and extend healthy life, rather than waiting until symptoms strike before we treat.

While we have always been optimists, we are now, for the first time, optimistic about a specific therapeutic strategy: antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) to lower prion protein in the brain. As explained in Sonia’s announcement post, ASOs as a class of drugs are showing great promise in treating neurological diseases. An ASO for spinal muscular atrophy just received FDA approval in December 2016 and has transformed the treatment of that devastating disease. Another ASO for Huntington’s disease is currently in clinical trials and has promising preliminary results showing that the causal protein (huntingtin protein, in that disease) was lowered by 40% in cerebrospinal fluid. ASO drugs are each made of the same basic building blocks — chemically modified versions of the A, C, G, and T that make up your DNA — stitched together in a different order, or sequence, to target different genes that cause different diseases. Therefore, if it’s possible to design an ASO to lower huntingtin protein by 40% in Huntington’s disease, there is no reason in principle why we shouldn’t be able to achieve the same for prion protein in prion disease. And because the molecular cause of prion disease is very well understood, we can be confident that lowering prion protein by 40% would be beneficial. Meanwhile, the success in other diseases has taught us a lot about the delivery, safety, stability, and distribution of ASO drugs. All of these aspects make this a promising route to pursue for a prion disease drug.

We showed survival curves from animal studies of ASO efficacy against prion disease. In Dr. Caughey’s lab, animals treated with ASOs starting prophylactically (before prion infection) lived ~70 - 90% longer than untreated animals. We have replicated this finding in our own lab, with treated animals living 61 - 77% longer with just two doses of ASO.

If things go well, it is possible that an ASO drug could enter clinical trials within 5 years. While we can’t count on this timeline, we do need to do everything we can to make it possible, and there is a lot we need to do now to lay the groundwork for the right trials. All past clinical trials in prion disease have focused on symptomatic patients, and that could be one route for ASOs as well. However, we know from other diseases that a drug effective at preventing disease might not be effective once the disease strikes — imagine taking a cholesterol-lowering drug at the moment you’re having a heart attack. So if we want to benefit presymptomatic patients, we need to think early about how to do clinical trials in presymptomatic patients as well.

Towards this end, we worked with CJD Foundation and CJDISA to launch the Prion Registry last year, as a place where people affected by or at risk for prion disease can find ways to participate in research and can stand up and be counted. We also launched a clinical research study at Mass General Hospital where mutation carriers and controls can donate CSF and blood for research to help us characterize biomarkers that we hope to one day use in a clinical trial in presymptomatic people.

CJD Foundation Reports

Mayra Lichter, Marie Kassai, and Brian Appleby provided updates on CJD Foundation’s activities and grants.

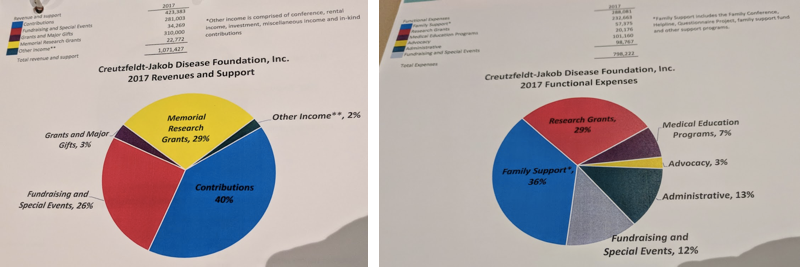

CJD Foundation’s mission includes supporting families, raising awareness, educating professionals such as neurologists and funeral home directors, advocacy, and advancing research. Its budget breakdown reflects all of these priorities:

CJD Foundation achieved a major advocacy victory last year. As explained in the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, there was a budget proposal to eliminate the $6 million congressional line item appropriation that funds prion disease surveillance (this is awarded to CDC, which sub-awards about half of it to the surveillance center in Cleveland). But thanks to patients and families who climbed Capitol Hill and spoke to their legislators, the full amount was eventually included in the budget that passed.

CJD Foundation’s grants program is expanding rapidly — it has raised $1 million in its history, but about $900,000 of that has been in just the past four years. It awarded $200,000 in grants last year and is on track to achieve the same level this year. Here is information on the funding cycle for this year’s call for proposals, which is still open (letters of intent are due August 1):

Brian Appleby - National Prion Disease Pathology Surveillance Center (NPDPSC) overview and panel

Dr. Appleby provided an overview of the activities of the surveillance center, which include diagnostic testing, genetic testing, autopsies, physician consultation on MRI diagnostics, and collaboration with key organizations including CDC and CJD Foundation. They currently receive about 400 autopsy referrals per year, of which ~70% do turn out to be prion disease. They perform diagnostic testing on about 3,500 - 4,000 cerebrospinal fluid samples. He also discussed their priorities going forward, which include:

- Developing better diagnostic tests, including application of RT-QuIC to any and all available tissues in addition to cerebrospinal fluid.

- Assisting CDC in monitoring the threat of deer and elk prion disease (chronic wasting disease, CWD) which is now found in 24 states and is still growing. One hope is to develop a diagnostic test that would distinguish any human prion disease arising from CWD exposure from normal CJD.

- Focusing on “fringe” cases, i.e. unusual cases which may require extra attention to make sure they do not reflect an infection event.

- Increasing outreach to potential referring physicians.

- Continuing to provide resources to researchers — NPDPSC is a major source of tissue samples for research (including our research at the Broad Institute).

One important achievement of the surveillance center in the past year was the publication of a major study evaluating the transmission risk posed by skin samples from CJD patients [Orru 2017]. The study was funded in part by a CJD Foundation grant to principal investigator Wenquan Zou. See this blog post for more information.

Kevin Keough - Alberta Prion Research Institute (APRI) Report

Dr. Keough gave an overview of the activities of APRI and its principal investigators. They have a long-running study exposing monkeys (cynomolgus macaques) to deer CWD prions, with preliminary evidence that the disease is transmissible to these monkeys, as previously reported in the news. For experimental details, see Stefanie Czub’s presentation at Prion2017.

We had to leave for the airport midway through Dr. Keough’s presentation; my notes from the rest of the talks are based on the slides handed out in the binder.

Ryan Maddox - CDC Report

Among CDC’s activities is to monitor how common prion disease is, through analysis of death certificates, where the cause of death may be listed as prion disease. They also compare these data to the data from the prion surveillance center, where diagnostic tests and autopsies are performed. About 5% of cases with prion disease listed as cause of death on the death certificate can be ruled out as false positives based on surveillance data, but they also add in cases equaling 13% of the total when they consider cases that did not have prion disease listed as cause of death but do have positive evidence for prion disease from the surveillance center.

Based on death certificate analysis from 2003-2015, they are currently finding an incidence (number of new cases per year per population) rate of 1.2 cases per million people per year. This translates into a very low risk among young people — there were only 10 cases age <30, for an incidence of 6.2 cases per billion per year — and a higher risk among older people, with 5.9 cases per million per year among those age ≥65. Remember that incidence is an annual figure, and so these numbers do not reflect an individual’s risk of eventually developing prion disease in their lifetime. When they consider prion disease deaths as a proportion of all deaths in the U.S., they find that ~1 in 6,000 people dies of prion disease. This figure is a better estimate of lifetime risk in the general population. When you consider some of the coincidences that Bob Will talked about in his keynote, such as a husband and wife both dying of prion disease, or a number of cases occurring in one small town, you have to consider this ~1 in 6,000 figure as the relevant estimate of how common prion disease is.

Dr. Maddox also spoke about variant CJD, of which four cases have been observed in the U.S. but none are believed to have been acquired in the U.S., and CWD, for which there is still no strong epidemiological evidence for transmission to humans but the CDC is continuing to study and monitor the situation.

Whitney R. Steele - CJD blood donor lookback study

Dr. Steele is at the American Red Cross where they are studying the potential for risk of prion disease transmission through blood transfusion. It is known that variant CJD has been transmitted by blood transfusion [Llewelyn 2004, Davidson 2014], but so far there is no evidence that sporadic CJD has ever been transmitted by blood transfusion. The Red Cross’s study likewise finds no evidence for transfusion risk in sporadic CJD. They have collected data on 71 blood donors who later died of sporadic CJD, and 894 traceable recipients of the donated blood followed for an average of several years, for a total of 4,205 person-years of follow-up. None of those individuals had CJD as a cause of death.

Update 2018-11-07: CJD Foundation has now posted YouTube videos of several of the talks.