Recombinant prion protein QC

Sonia and I are continuing to seek out new ways to discover small molecules that bind PrP. Every time we meet with a new potential collaborator, or someone who we’re asking to teach us a technique, or a particularly astute candidate for the open position in our lab, their first question is always (justifiably) what have we done to make sure our protein is good? I finally decided to just compile the answer to that question into this blog post and send people here.

How we make recombinant PrP

We purify recombinant PrP using essentially the Rocky Mountain Recombinant protocol, with a few minor modifications (discussed further below). We use “full-length” (HuPrP23-230, lacking the signal peptide and GPI signal found in the mammalian gene and thus corresponding to the mature, post-translationally cleaved protein) or N-terminally truncated (HuPrP90-231) protein. These constructs are not tagged nor cleaved, and thus retain an N-terminal methionine not present in mature PrP expressed in mammalian cells. The purification relies on PrP’s intrinsic affinity for metals, allowing it to be purified like a His-tagged protein even though it lacks a His tag. The proteins are expressed in E. coli, and the proteins in inclusion bodies are isolated by fractioning, denatured in guanidine, loaded onto Ni-NTA beads, refolded on an AKTA fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) machine, and eluted with imidazole.

The minor changes we’ve made versus the original protocol are:

- Increased protein loading. We have on some occasions increased the amount of protein we try to load onto the beads. The original protocol says not to put more than the equivalent of 750 mL of bacterial culture into a 26x20 column containing 54g (which is tens of mL) of Ni-NTA resin, with a typical yield being maybe 50 mg. That means you’re trying to bind on the order of 1 mg of protein per mL of resin. For comparison, For instance, Qiagen’s specs for the Ni-NTA superflow resin advertise a binding capacity of up to 50 mg protein per mL of resin. I was inspired to get slightly more adventurous and in PrP batch 19 I tried loading 2 L of bacterial culture worth of solubilized inclusion bodies onto one column, and indeed, I got a yield of 190 mg.

- Higher pH elution. The original protocol calls for elution in a gradient to 500 mM imidazole at pH 5.8. This practice appears to date back to [Zahn 1997]. The QIAExpressionist notes that you can elute His-tagged proteins with either acid (to protonate the histidines that bind the nickel) or imidazole (to compete away the histidines), but the idea of using acidic pH and imidazole at the same time is bizarre. Free imidazole actually has a higher pKa than histidine (about 7 vs. 6), so by the time you’ve protonated the protein’s histidines enough to reduce their binding, the imidazole should be so thoroughly protonated that it no longer competes. At pH 5.8, one can calculate that ~95% of the imidazole should be protonated. Indeed, even the process of making a 500 mM imidazole solution at pH 5.8 just feels wrong: you’re standing there at the pH meter forever, dumping in milliliters upon milliliters of 37% HCl, protonating all that imidazole that’s supposed to elute your protein. We therefore did the experiment of trying to elute PrP at pH 5.8 without imidazole and, as expected, nothing eluted — the QIAExpressionist says you need a pH more like 4.5 if you want to elute with pH alone, and once we lowered the pH to 4.5, we finally saw our protein elute. With a different batch, we then tried eluting in 500 mM imidazole at pH 8.0, and we saw robust elution. I concluded that the low pH in the original protocol is not contributing to elution efficiency. Indeed, I suspect the only reason it even works at all is that it’s run as a gradient, so that as the elution buffer gets gradually titrated into the refolding buffer, the pH stays high enough long enough that you have a window where the effective un-protonated imidazole concentration is just high enough to elute the protein. Thereafter, we started eluting all our protein in 500 mM imidazole at pH 8.0, although we’ve since noticed that we may be getting ~10% reduced cysteines (see below) at this pH, so in the future we may shift down a bit to pH 7.0 or something.

Since our first batch at Broad a year and half ago, we’ve run the protocol about 20 times, making various constructs (HuPrP23-230, HuPrP90-231, SHaPrP90-230, and MoPrP23-230, as well as HA- and SNAP-tagged PrPs which have been less successful) dialyzed into different buffers (phosphate, HEPES, different pHs, with or without EDTA). We have gotten excellent yields, of about 50 - 100 mg per liter of bacterial culture. We have never performed an exhaustive set of QC experiments all on a single batch of protein, but we’ve done a patchwork of experiments on different batches to convince ourselves that the protein we’re making is legit.

Circular dichroism to interrogate secondary structure

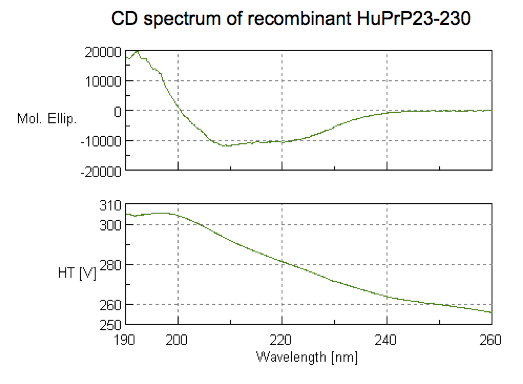

As described in this blog post, we performed circular dichroism (CD) on our first Broad-purified batch of PrP. CD measures absorption of circularly polarized UV light to gain information about protein secondary structure. Here’s the CD spectrum we obtained for HuPrP23-230:

It is consistent with substantial alpha helical content, as alpha helices tend to give local minima around 208 and 222 nm.

Melting temperature by a few methods

The literature gives a range of melting points for PrP, from about 66 - 71°C [Nicoll 2010, Calzolai & Zahn 2003]. We’ve measured the melting point of our PrP by three methods.

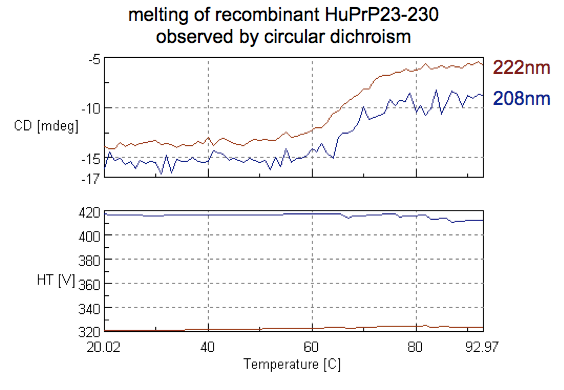

First, we used CD (see above). As covered here we monitored 208 and 222 nm — two wavelengths indicative of alpha helical content — while heating the protein from 20 to 90°C:

The results show a melting point in the mid to high 60s °C, consistent with expectation.

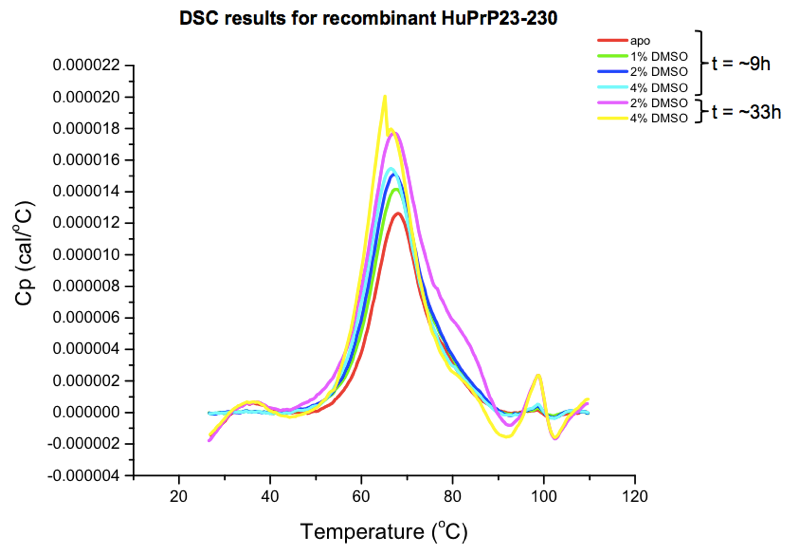

Next, we used differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), which directly monitors protein unfolding via heat capacity — the amount of heat energy needed to raise the temperature each degree. As described here HuPrP23-230 gave us a melting point around 67°C, which dropped slightly but not catastrophically after 24+ hours in up to 4% DMSO:

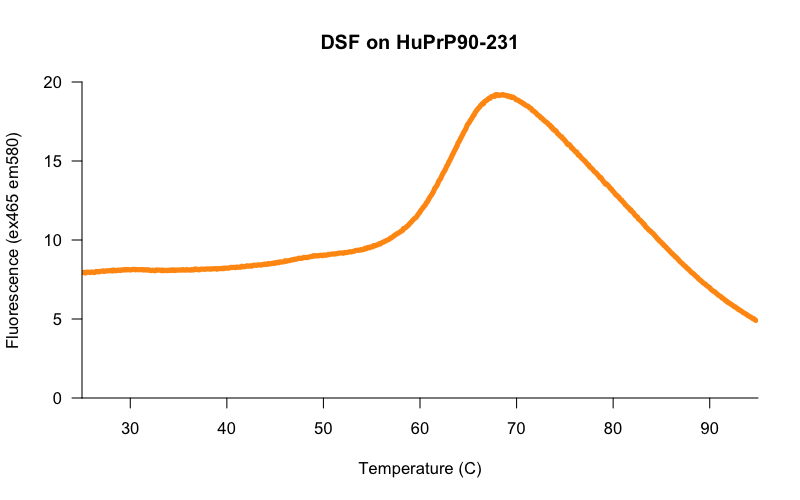

Finally, and as I’ll explain more in an upcoming post, we have also performed a battery of differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) experiments, which monitor the emission of a dye that fluoresces when bound to hydrophobic patches of unfolded proteins in order to infer melting point.

Here’s a randomly chosen melting curve from a plate of PrP batch 13 (HuPrP90-231) in 20 mM HEPES, 25 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA at 50 μM, melted in a white lightcycler plate in a Roche Lightcycler 480 on the protein melt program, with 10X Sypro Orange dye and 2% DMSO:

The midpoint of the increase in fluorescence looks to be somewhere in the low 60s °C.

Remember that each of these three methods is measuring something different: heat capacity (DSC), secondary structure (CD), and exposure of hydrophobic residues (DSF), so it’s not a big deal if we don’t get the exact same melting point from the three methods, but it is reassuring that we see results that are all roughly consistent with one another.

TROSY NMR spectrum and stability

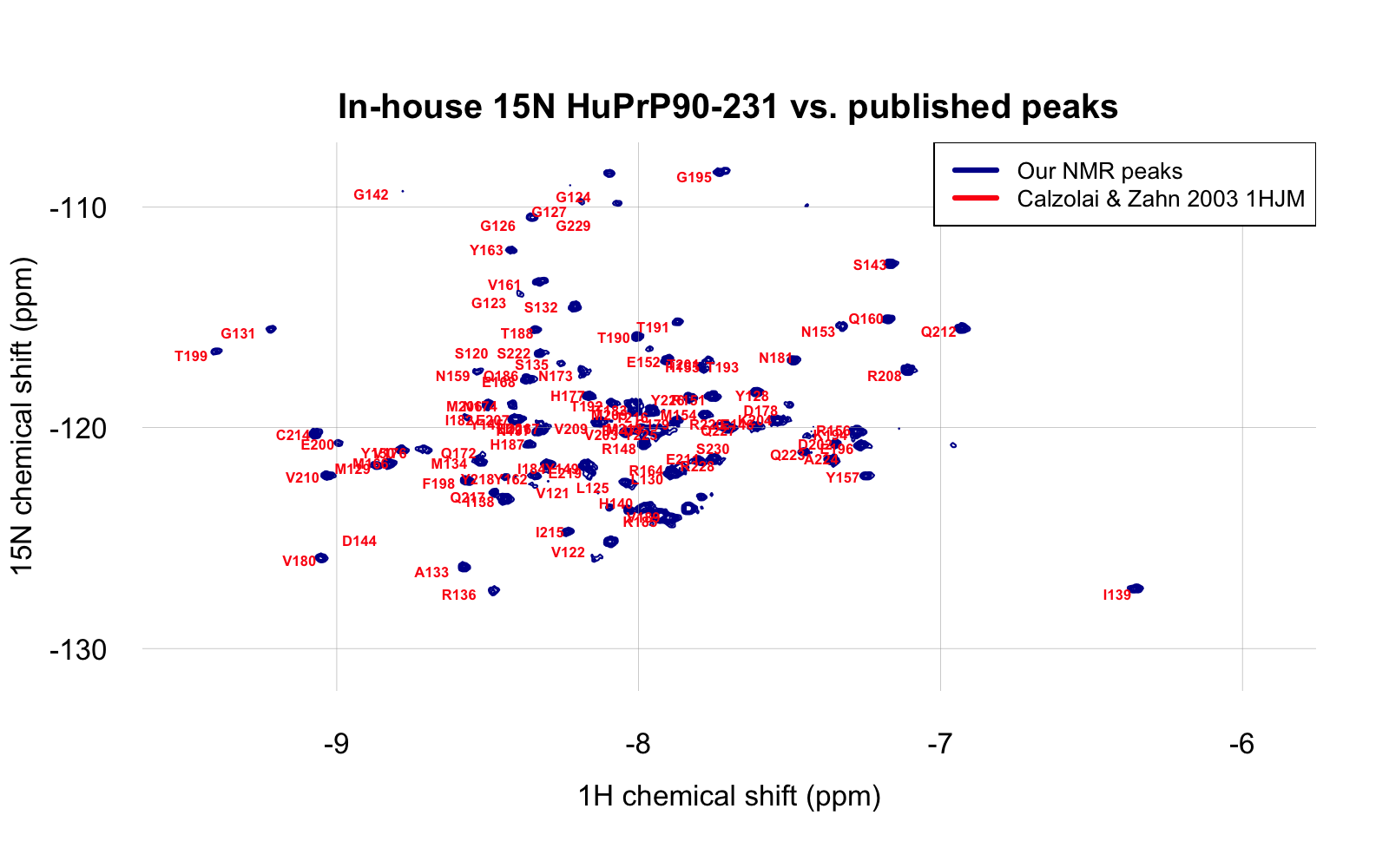

We’ve produced two batches of 15N-labeled PrP in order to do 2D protein-observed NMR. One batch was HuPrP23-230 at pH 5.8, described here. It was possible to assign some of the peaks, but the plot was a bit crowded, in part because many of the amino acids from the unstructured region of the protein had peaks very close to each other. We later made a batch of 15N-labeled HuPrP90-231 which I dialyzed into 20 mM HEPES, 25 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA at pH 6.8. It was thus somewhat closer to the construct (HuPrP121-230) and conditions (pH 7.0 in phosphate buffer) used in one reported structure, 1HJM [Calzolai & Zahn 2003]. Our NMR spectrum, obtained with 50 μM protein using TROSY on a Bruker 600 MHz spectrometer, proved to line up beautifully with the reported peaks from the 1HJM structure. To be able to compare HSQC and TROSY, I added 0.2 to the 1H HSQC shift and subtracted 1 from the 15N HSQC shift. Once I did this, the reported peaks and our peaks line up very nicely:

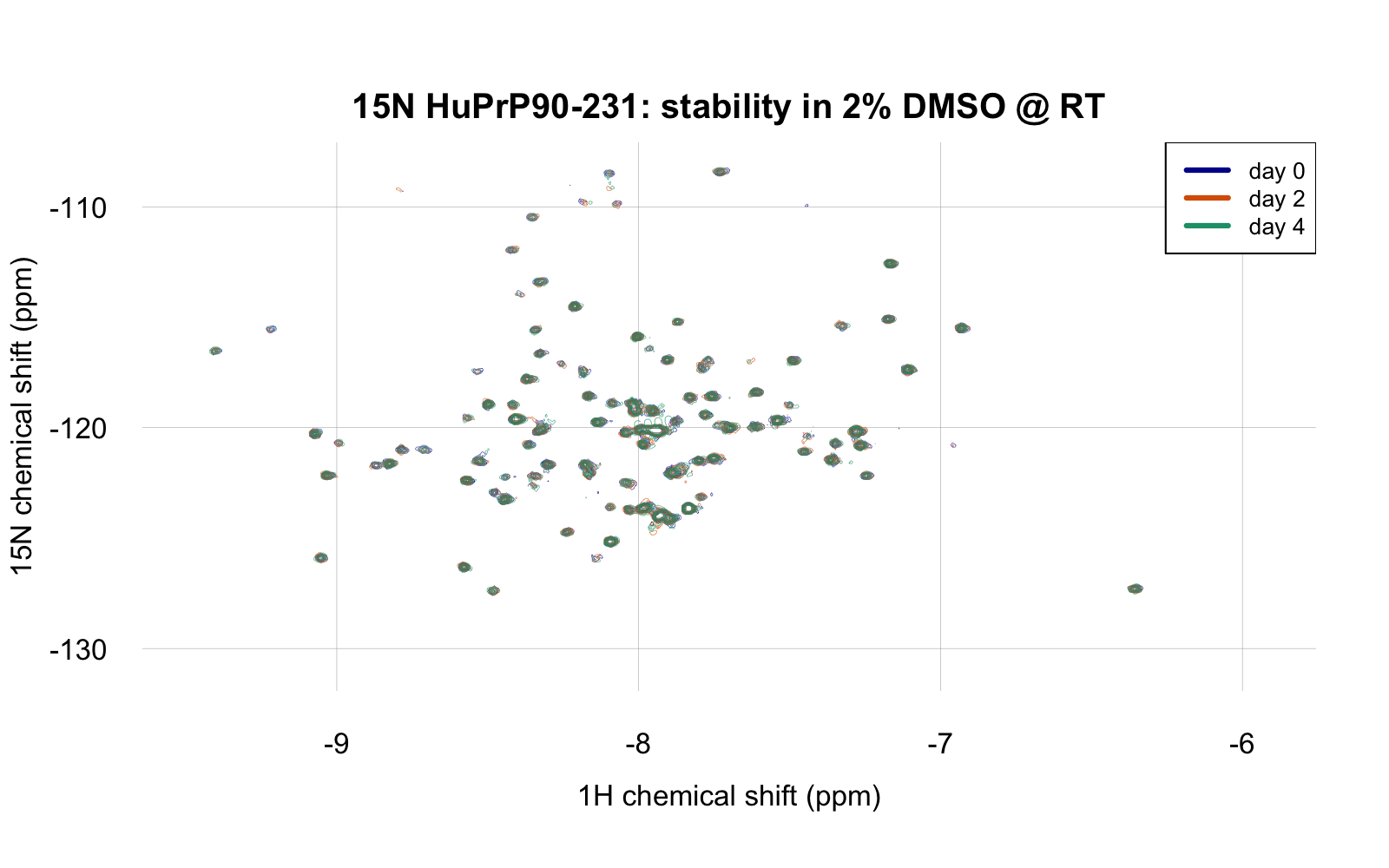

The above is at day 0, with 2% DMSO. To test whether our protein is stable enough in these conditions to wait in the queue for a screen to run, I let it sit at room temperature for four days, acquiring a TROSY spectrum again on day 2 and day 4:

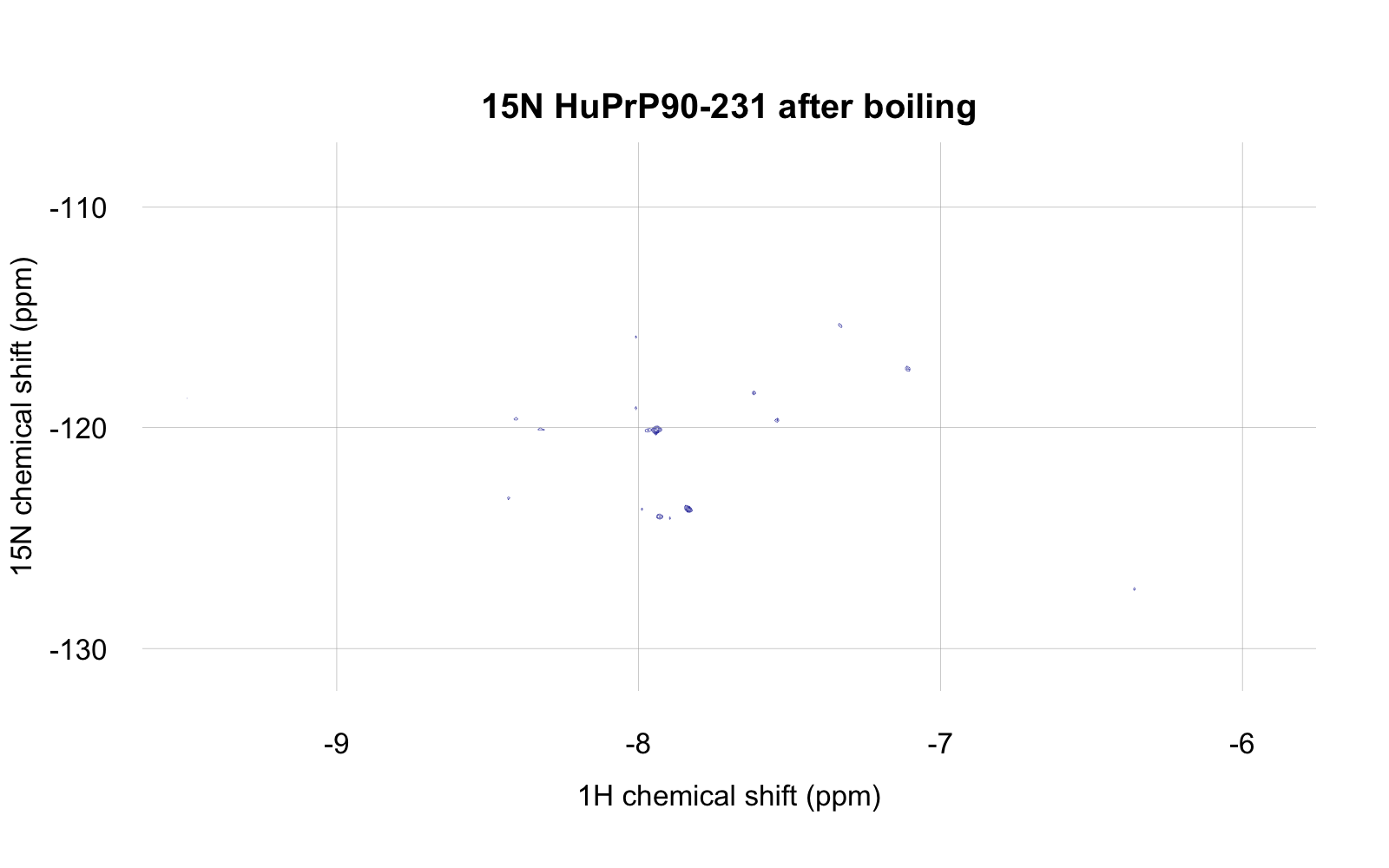

If you feel you’re squinting and can’t really make out the different days, you can’t — they overlap perfectly. The spectrum didn’t change a bit, which is very reassuring about the stability of this protein in this buffer with 2% DMSO. As a positive control to check that the spectrum would change if the protein were denatured, I then boiled the protein by heating to 95°C for 5 minutes, whereupon it almost instantly formed visible white precipitate. When I returned it to the NMR spectrometer, here’s what I saw (at the same zoom level as above):

So yes, the spectrum does go away if the protein is precipitated.

We haven’t done the analogous experiment for HuPrP23-230.

Dynamic light scattering to test for aggregation

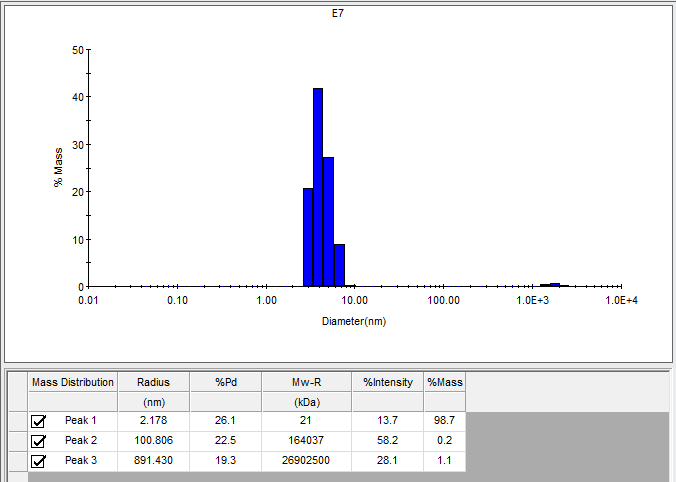

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) is a technique for determining the size of particles in solution, based on the principle that larger particles scatter more light. Our labmate Zarko Boskovic taught us to do DLS, starting with our PrP batch #19. This was a batch of HuPrP90-231 where I ambitiously combined 2 liters of bacterial culture worth of inclusion bodies into a single column to see if I could recover the full yield. (We were taught to only use 750 mL equivalent per column, but the loading capacity of Qiagen superflow Ni-NTA beads is advertised as being much higher, so we wanted to try). Indeed, the yield was 190 mg, eluted in a small volume at a concentration of 112 μM (about 1.8 mg/mL). It was dialyzed into 20 mM HEPES, 25 mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA pH 6.8 and freeze/thawed before doing DLS. If there were ever a batch of PrP to aggregate, you might worry it would be this one. But the DLS results supported ~99% of particles being of ~4.3 nm radius, consistent with a PrP monomer:

Large aggregates were present, but only accounted for 1.3% of the mass. These could presumably be removed by spinning the protein through a 100 kDa cutoff PALL filter, which we do routinely for RT-QuIC but had not done for DLS.

As you can see, the particle size estimated from the light scattering has quite a range, with 4.3 nm diameter being the mean. The software estimates that this corresponds to a 21 kDa molecular weight; our HuPrP90-231 monomer should be 16 kDa. But my understanding is that this is well within the error of the method; indeed, some folks I spoke with believed that for a protein of this size, DLS could not even distinguish a monomer from a dimer.

Coomassie gels to assess purity

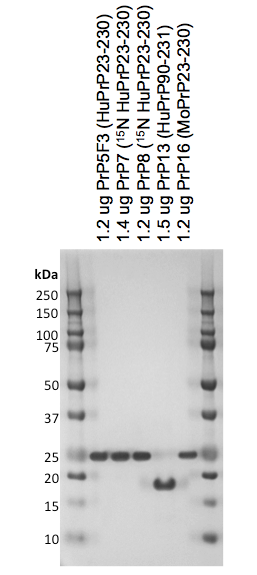

My colleague Emily Ricq ran a few of our different protein batches on a Coomassie gel to assess their purity, for instance:

All were the expected molecular weight (~22 kDa for full-length and ~16 kDa for truncated) and no other bands were really visible at all, so the purity is probably at least 95%.

One peculiarity she noted was that PrP19 (the high concentration HuPrP90-231 mentioned above) when run on a gel after boiling in SDS had about 10% apparent dimer content. She hypothesized these were intermolecular disulfide dimers formed during the boiling in SDS for the gel, and sure enough, when she alkylated the protein with iodoacetamide prior to boiling, the dimers went away. So the conclusion, then, is that at least this one batch of protein has about 10% of the protein in a reduced state (PrP’s native state is to be oxidized). A possible reason for this is that this batch was refolded at pH 8.0 and eluted in a gradient to 500 mM imidazole at pH 8.0 before being dialyzed into a pH 6.8 buffer. The pH 8.0 buffers are close enough to the cysteine side chain pKa of 8.37 (source) that some of the intramolecular disulfide bonds may not have formed properly. In the future we may try eluting or even refolding at a lower pH to minimize this problem.

Positive control binders

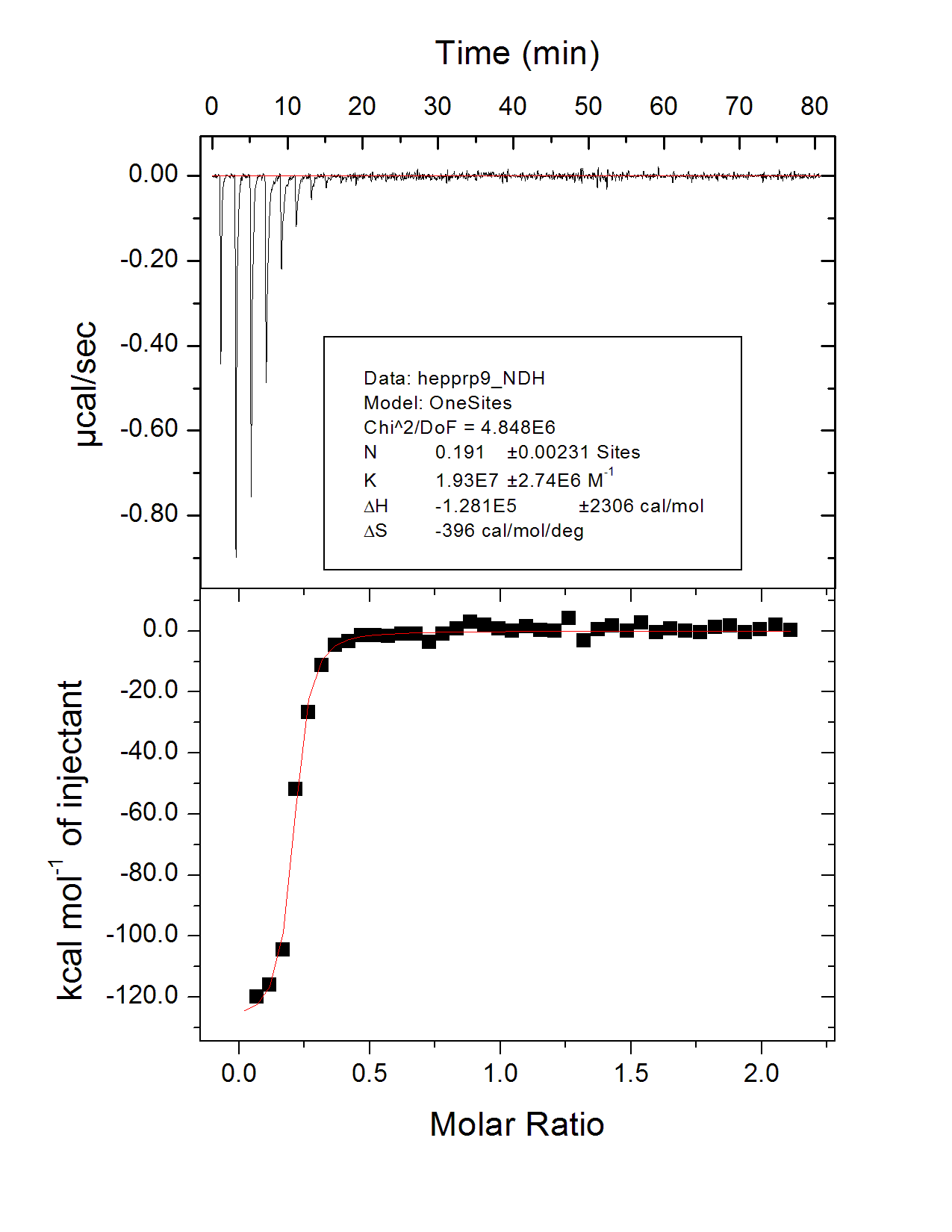

There aren’t any really good, specific, 1:1 small molecule binders of PrP — that’s the whole point of our small molecule effort — but we have tested a few positive controls to see if we see binding. As explained here, we did observe FeTMPyP binding to PrP as others have observed, with a Kd of ~20 μM. More recently we also tested heparin, which is one of the several sulfated glycans shown to bind PrP [Caughey 1994]. The heparin we bought from Sigma was purified from a natural source (porcine intestine) and comes with no claim as to even an average molecular weight, but if we assume as a wild guess a molecular weight of 10 kDa, then we saw a Kd of 51 nM for binding to HuPrP23-230 by isothermal titration calorimetry. This was batch 22, HuPrP23-230 at 10 μM dialyzed into 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 7.0.

Sensitivity to prions in RT-QuIC

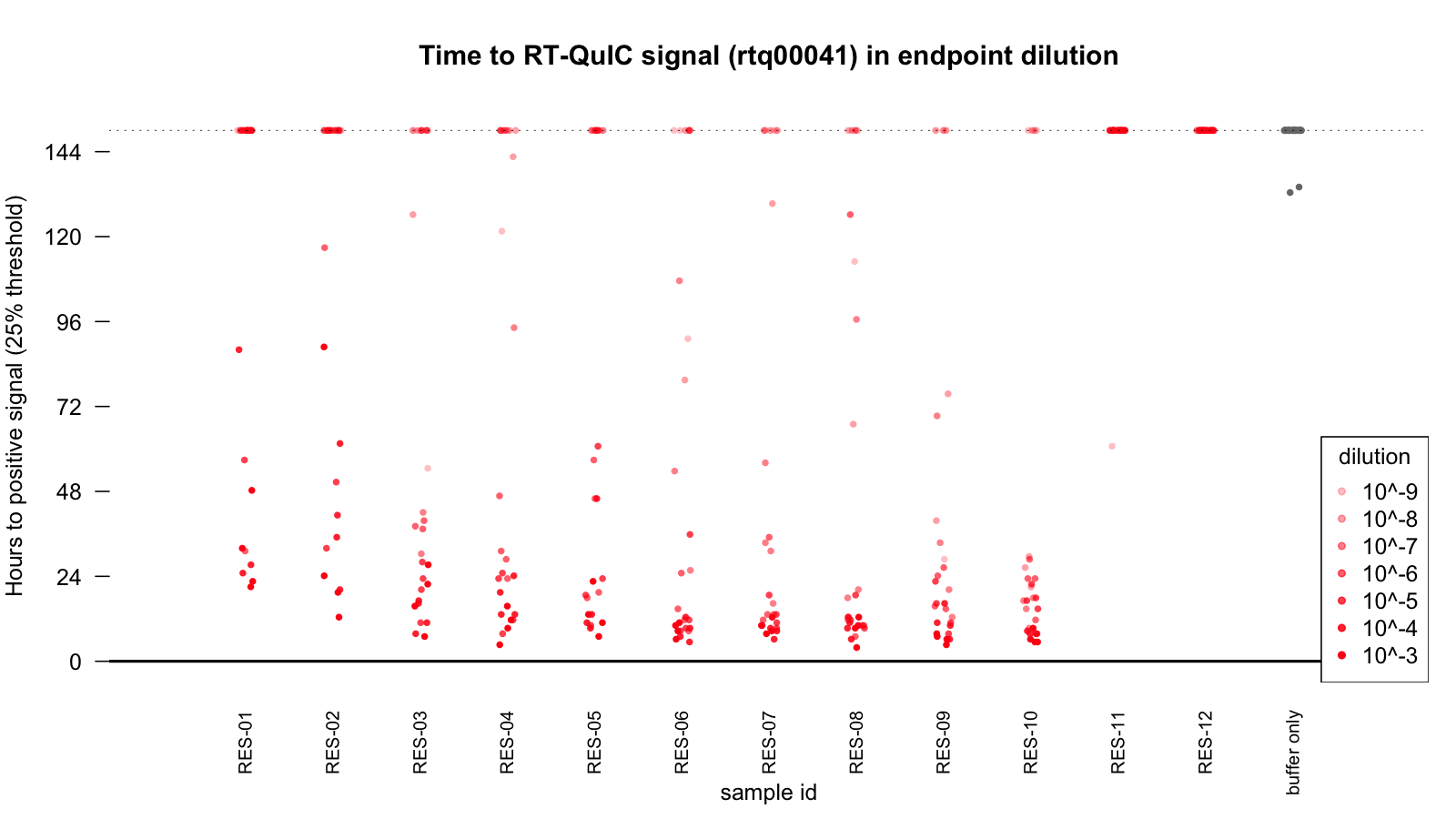

Another good test of one’s recombinant PrP quality is the ability to specifically detect prions in RT-QuIC. We had 12 de-identified human brain samples that a collaborator had sent us for our research, and we were blinded as to which individuals had prion disease and which did not. We used our PrP batch 6 (HuPrP23-230) to run an RT-QuIC with brain homogenates from all 12 samples at a 10-3 down to a 10-9 dilution, plus a buffer-only control. We did this in a 384-well plate with a 25 μL reaction volume and a 0.5 μL seed, thus making it possible to fit this whole matrix of experiments onto a single plate. (For RT-QuIC aficionados, this experiment was done at 42°C in a Fluostar Optima platereader shaking at 600 rpm 1 minute on, 1 minute off; the master mix was “low salt” (~130 mM NaCl just from PBS) and the brain homogenates had 0.1% SDS.) Here’s a scatterplot of the times at which positive ThT fluorescence was detected:

As you can see, fluorescence increased by 25% over baseline within a few hours at strong dilutions, and within a day or two at lower dilutions, for 10 of the samples, while the final two samples were negative out to at least 6 days, with only a single well flukily turning positive. We concluded these two samples were the non-prion controls, and the collaborator who provided the samples subsequently confirmed this over email. Thus, our protein (or at least this one batch) seems suitable for detecting prions by RT-QuIC.

Conclusions

Overall it appears that we’ve succeeded in producing properly folded recombinant PrP here at the Broad, and we’re now using this PrP for a wide variety of different assays. But biology being what it is, there’s still no guarantee that any new experimental conditions — different buffers, different concentration, different pH — won’t affect our protein, and it’s still important to do additional QC experiments